On 28 June 1920, five men from C Company of the 1st Battalion of the Connaught Rangers led a mutiny in Jalandhar, Punjab, in protest against martial law in Ireland. Following their surrender a few days later, 88 mutineers were court-martialled, of whom 77 were imprisoned; the leader, James Daly, was executed. The imprisoned mutineers were released in 1923; they returned to Ireland, and in 1936 were granted State pensions. In 1970 the remains of James Daly and two other mutineers were repatriated from India.

Listen to Tommy Graham, editor of History Ireland, discuss the complex web of issues arising from these events and their commemoration both in 1970 and today with

John Gibney, Cécile Gordon, Brian Hanley and Kate O’Malley.

This podcast is part of the History Ireland Hedge School programme supported by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht under the Decade of Centenaries 2012–2023 initiative.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

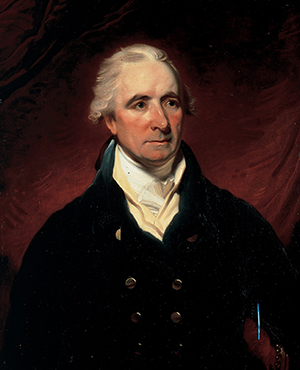

Born in Dublin’s Fishamble Street in 1746, but resident for most of his life in Tinnehinch, near Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow, Henry Grattan was the most noted, and certainly the most eloquent, of the eighteenth-century opposition ‘patriots’ in the Irish Parliament. He reached the height of his popularity with the concession of ‘legislative independence’ in 1782. Nineteenth-century constitutional nationalists would later refer to this, until its dissolution by the Act of Union in 1800, as ‘Grattan’s Parliament’, despite his almost permanent position on its opposition benches. In truth its ‘independence’ was a sham, and its inability to reform itself or grant Catholic Emancipation led to the polarisation of the 1790s and the bloody rebellion of 1798. By now a marginal figure, he spoke eloquently, but in vain, against the subsequent Act of Union. Less well known is his return to Parliament, this time in Westminster, in 1805, where he served until his death on 6 June 1820. To mark the bicentenary of his passing and to reassess his often misunderstood legacy, History Ireland editor Tommy Graham was joined, for an online Hedge School, by David Dickson, Patrick Geoghegan, Sylvie Kleinman and Tim Murtagh.

Born in Dublin’s Fishamble Street in 1746, but resident for most of his life in Tinnehinch, near Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow, Henry Grattan was the most noted, and certainly the most eloquent, of the eighteenth-century opposition ‘patriots’ in the Irish Parliament. He reached the height of his popularity with the concession of ‘legislative independence’ in 1782. Nineteenth-century constitutional nationalists would later refer to this, until its dissolution by the Act of Union in 1800, as ‘Grattan’s Parliament’, despite his almost permanent position on its opposition benches. In truth its ‘independence’ was a sham, and its inability to reform itself or grant Catholic Emancipation led to the polarisation of the 1790s and the bloody rebellion of 1798. By now a marginal figure, he spoke eloquently, but in vain, against the subsequent Act of Union. Less well known is his return to Parliament, this time in Westminster, in 1805, where he served until his death on 6 June 1820. To mark the bicentenary of his passing and to reassess his often misunderstood legacy, History Ireland editor Tommy Graham was joined, for an online Hedge School, by David Dickson, Patrick Geoghegan, Sylvie Kleinman and Tim Murtagh.

The general election of 8 February 2020 marked a seismic shift in Irish politics. The Fianna Fáil/Fine Gael duopoly, which had dominated for nearly a century, was shattered by a resurgent Sinn Féin, creating a novel tripartite division. To make sense of it all, and in particular to address any historical precedents, History Ireland editor, Tommy Graham, spoke with Brian Hanley, author of The Impact of the Troubles on the Republic of Ireland, 1968-79

The general election of 8 February 2020 marked a seismic shift in Irish politics. The Fianna Fáil/Fine Gael duopoly, which had dominated for nearly a century, was shattered by a resurgent Sinn Féin, creating a novel tripartite division. To make sense of it all, and in particular to address any historical precedents, History Ireland editor, Tommy Graham, spoke with Brian Hanley, author of The Impact of the Troubles on the Republic of Ireland, 1968-79

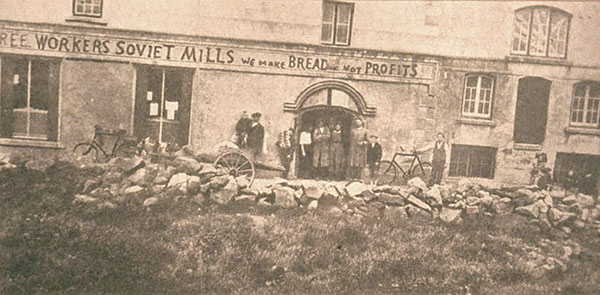

We apologise for the variable quality of the sound recording which was outside our control.

We apologise for the variable quality of the sound recording which was outside our control. @ Mechanics Institute, Galway (in association with the ICTU & the Irish Centre for the Histories of Labour and Class, NUI Galway)

@ Mechanics Institute, Galway (in association with the ICTU & the Irish Centre for the Histories of Labour and Class, NUI Galway)

The runaway success of the Atlas of the Irish Revolution (and the parallel TV documentary) and the proliferation of microstudies of the War of Independence and Civil War seems to bear out the adage that, like politics, all history is local. But is it? Do we risk losing sight of the ‘bigger picture’, of a world torn apart by war, revolution, and state formation? What, for example, can either approach tell us about violence directed at women, hitherto ignored in Ireland? To discuss these and related matters, History Ireland editor, Tommy Graham was joined for a lively discussion by John Borgonovo, Fearghal McGarry, Darragh Gannon and Linda Connolly.

The runaway success of the Atlas of the Irish Revolution (and the parallel TV documentary) and the proliferation of microstudies of the War of Independence and Civil War seems to bear out the adage that, like politics, all history is local. But is it? Do we risk losing sight of the ‘bigger picture’, of a world torn apart by war, revolution, and state formation? What, for example, can either approach tell us about violence directed at women, hitherto ignored in Ireland? To discuss these and related matters, History Ireland editor, Tommy Graham was joined for a lively discussion by John Borgonovo, Fearghal McGarry, Darragh Gannon and Linda Connolly.

March 2018 marks the centenary of the death of John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, which had dominated party political life since the heyday of Parnell in the 1880s. It would all but be wiped out by Sinn Féin in the December 1918 General Election. Was that inevitable? To what extent was Redmond responsible for this change or was it due to circumstances beyond his control? Is it fair in hindsight to judge Redmond on the final few years of a long and eventful career? Was the Treaty settlement of 1921 to a large degree ‘Home Rule for slow learners’ in any case?

March 2018 marks the centenary of the death of John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, which had dominated party political life since the heyday of Parnell in the 1880s. It would all but be wiped out by Sinn Féin in the December 1918 General Election. Was that inevitable? To what extent was Redmond responsible for this change or was it due to circumstances beyond his control? Is it fair in hindsight to judge Redmond on the final few years of a long and eventful career? Was the Treaty settlement of 1921 to a large degree ‘Home Rule for slow learners’ in any case?

On 10 September 1967, Minister for Education Donogh O’Malley announced a scheme for free secondary education, much to the surprise of his cabinet colleagues, and of the Department of Finance in particular. But once word was out, there was no going back; expectations had been raised and the public response was hugely supportive. Within a decade participation rates at second level had doubled. But to what extent was the system subsidized before the announcement? To what extent has it been ‘free’ since? And beyond education, what was its effect socially and economically?

On 10 September 1967, Minister for Education Donogh O’Malley announced a scheme for free secondary education, much to the surprise of his cabinet colleagues, and of the Department of Finance in particular. But once word was out, there was no going back; expectations had been raised and the public response was hugely supportive. Within a decade participation rates at second level had doubled. But to what extent was the system subsidized before the announcement? To what extent has it been ‘free’ since? And beyond education, what was its effect socially and economically?