‘Degenerating from sterling Irishmen into contemptible West Britons’: the GAA and rugby in Kerry, 1885–1905

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2011), Volume 19 For the first two decades of the GAA’s existence, rugby rather than Gaelic football was seen by many as Kerry’s pre-eminent sport. That rugby should have attained popularity in the county is hardly surprising. The traditional game of ‘caid’ had been popular among the Kerry peasantry for centuries. Rugby’s spread into Kerry in the early 1880s was greatly facilitated by the characteristics it shared with caid. Both involved scrimmages of men attempting to gain possession before passing to the fleeter-footed players hovering on the wings, who ran with the ball in hand. It seems likely that the rules for rugby as they evolved were having a growing effect on caid. Increasingly the game began to forgo its cross-country element and became confined within a defined playing field, between two teams of equal numbers.

For the first two decades of the GAA’s existence, rugby rather than Gaelic football was seen by many as Kerry’s pre-eminent sport. That rugby should have attained popularity in the county is hardly surprising. The traditional game of ‘caid’ had been popular among the Kerry peasantry for centuries. Rugby’s spread into Kerry in the early 1880s was greatly facilitated by the characteristics it shared with caid. Both involved scrimmages of men attempting to gain possession before passing to the fleeter-footed players hovering on the wings, who ran with the ball in hand. It seems likely that the rules for rugby as they evolved were having a growing effect on caid. Increasingly the game began to forgo its cross-country element and became confined within a defined playing field, between two teams of equal numbers.

Early spread of rugby

Rugby was quick to spread into the larger towns of Kerry: Tralee Rugby Club was founded in 1882 and took part in the inaugural Munster Senior Cup in 1886. How the game was introduced into Kerry is difficult to establish with accuracy. The growth of the game in the towns could be attributed to university graduates like Tralee’s star out-half Dr John Hayes, who was introduced to rugby as a student in the Royal College of Surgeons, Dublin. It is possible, just as was often the experience in Britain, that graduates of such institutions, once they moved home, brought with them knowledge of the sport to their local area. Another factor in the spread of the game was the presence of foreign companies, such as the Anglo-American Cable Company, in areas like Valentia from the 1860s onwards. British employees familiar with the game may have introduced it to the islanders to form a local club.

Formation of the GAA in Kerry

The first branch of the GAA in Kerry was formed in Tralee on Sunday 31 May 1885, but it was only in early 1888 that steps were taken for a countywide establishment of the organisation. Kerry’s first annual GAA convention was held in Tralee on 7 November 1888, when nineteen clubs were represented and Kerry’s first county board was formed. The following year the inaugural county championships were held, and Kerry made her debut in the Munster championship, represented in hurling by Kenmare and in football by Laune Rangers. Under the influence of its captain, J.P. O’Sullivan, the latter club in October 1888 held a meeting and decided to forgo playing rugby and to declare instead for Gaelic football, a sign of the growing influence of the GAA.

Though the GAA in 1886 passed a rule forbidding members of other sporting bodies from becoming members of the association, the relationship between Gaelic football and rugby in Kerry, in these early years of coexistence, remained ambiguous. This is not surprising, given the similarities between caid, rugby and early Gaelic football. For example, ten players lined out both for Killorglin rugby club in February 1888 and for Laune Rangers Gaelic football team in the 1890 county championship. Rugby was popular enough that at a meeting of Tralee Mitchels GAA club in October 1888 some members enquired about forming their own rugby club in the town, only to be reminded that this was forbidden by the constitution of the GAA. At a meeting of Mitchels the following February a charge was brought against four members for playing rugby in the town.

GAA decline

Despite the presence of rugby, the GAA in Kerry witnessed remarkable growth, with 33 clubs affiliating in 1889. This success proved illusory, however. By the following year, with the effects of a long-term agricultural depression already evident, GAA activity in Kerry was in decline. This should not be surprising, as some 61.8% of GAA members were involved directly in agriculture. The decline was exacerbated by the fallout from the Parnell split in December 1890. Throughout 1891 this would lead to bitter and heated arguments in the Kerry GAA between pro- and anti-Parnell factions. In addition, the 1890s saw the flow of emigration, which had slowed to a trickle in the late 1880s, become a torrent. Census reports show that Ireland’s population decreased by 5.3% in the decade after 1891. The Kerry Sentinel reported that 83.7% of those who emigrated in 1896 were aged 15–35—exactly the age group of young men upon which the GAA depended. The combination of these factors almost destroyed the GAA as an organisation. In 1896 it sought to bolster its membership by revoking its ban on ‘foreign games’.

Only a strong and driven county board could have hoped to keep GAA activity going during these desperate times. But the GAA in Kerry received a potentially mortal blow in March 1897 when Thomas Slattery, who had been president of the county board since its inception in 1888, declined to allow his name to go forward for re-election. Robbed of his energetic and forceful leadership, the GAA in Kerry practically ceased to exist. Board meetings soon collapsed and the county championships were allowed to lapse.

Survival of rugby

In the midst of these difficulties rugby survived, principally in larger towns like Tralee. Tralee RFC continued to compete in the Munster Cup. Players from the club were of a high enough standard to impress in a provincial trial game for Munster in January 1895. In that same year Dr William O’Sullivan of Killarney captained Queen’s College, Cork, to victory in the Munster Cup and also won an Irish cap against Scotland. The removal of the ‘foreign games’ ban led to a definite upswing in rugby’s fortunes in the county. No longer affected by any stigma associated with the sport, and in the absence of GAA activity, those young men who were in a position to crossed over.

In examining the social profile of a sample of Gaelic football and rugby players in Kerry (see graph, p. 29), we find an enormous disparity between the 61% of GAA members engaged in agriculture and the 2.5% per cent of rugby players. Thus, unaffected by the agricultural depression, men in large towns who might otherwise have played Gaelic football turned to rugby. Towards the end of 1898, public meetings were held in Killarney and Dingle to re-form rugby clubs. The status that rugby had attained in Kerry was evident when Tralee was chosen as the venue for the interprovincial match between Munster and Leinster in January 1900. Reports of the game noted the large crowd and that gate receipts proved ‘beyond all expectation’. The town was selected by the Munster branch ‘to stimulate rugby in the county of Kerry’. Directly after the game, four Tralee men were selected for the Munster team to play Ulster. That April, Tralee caused the shock of the Munster Cup by beating Cork Constitution in the semi-final and qualifying for their first final, where they lost to Queen’s College, Cork.

Rugby was revelling in a newfound popularity in Kerry. Unchecked, this might have completely altered the sporting history of the county. But one GAA official, Thomas F. O’Sullivan, put his energy into re-establishing the GAA and led a campaign for the reintroduction of the ‘foreign games’ ban. O’Sullivan was the Kerry Sentinel’s reporter for his native Listowel after leaving St Michael’s Secondary School. His formative years came at a time of great change and upheaval in Irish society. Because of his occupation, O’Sullivan would, more than most, have come into contact with the new political and cultural movements developing in Ireland in the 1890s. He was horrified by the growth of ‘foreign games’, especially rugby. A likely catalyst for this stance was that during his last days at St Michael’s its principal, Fr Timothy Crowely, had introduced cricket and rugby into the college. Ruefully observing the utter lack of organisation in GAA activity, O’Sullivan took it upon himself to reawaken the county from its lethargy. In early 1900 the GAA central council, anxious that Kerry should be brought back into the association’s fold, dispatched two officials to help O’Sullivan to organise the county. A GAA convention was organised in Tralee on 26 May. This proved a huge success: a new county board was elected, with O’Sullivan as its honorary secretary. Twenty football and four hurling teams formally affiliated to the new board.

Moss Keane

Cultural nationalism

O’Sullivan next turned his considerable rhetorical and journalistic skills to crushing the threat posed by ‘foreign’ sports to Gaelic games. A product of the new cultural nationalism of the time, this outlook coloured everything O’Sullivan said or wrote. For him the GAA represented nationalist culture and was a bastion in an ideological battle for Ireland’s sports fields. Against it stood rugby, which, to O’Sullivan, embodied foreign British rule. From 1901 the GAA found itself caught up in the ‘snowball effect’ of the new nationalism. O’Sullivan thus had a ready audience within the GAA for his nationalist views. At the adjourned annual convention in December 1901, delegates voted in favour of O’Sullivan’s motion:

‘That we call on the young men of Ireland not to identify themselves with rugby or association football or any other form of imported sport which is likely to injuriously affect the national pastimes’.

O’Sullivan was aware of the immense potential of the press to reach and influence a far wider audience than at any other time in Irish history. Having secured the moral force of GAA opinion, O’Sullivan, now the Sentinel’s GAA correspondent, launched a campaign through the press to undermine and destroy the popularity of‘English pastimes’ in Kerry. ‘In my humble opinion the persons who are promoting the extension of rugby, association football, and the other anglicising agencies . . . are doing more to blot out our nationality than the British government.’ He argued that if Gaels drew inspiration from native instead of foreign sources, the result of which wasa ‘degenerating from sterling Irishmen into contemptible West Britons’, ‘there would be no fear of the ultimate triumph of our national cause’.

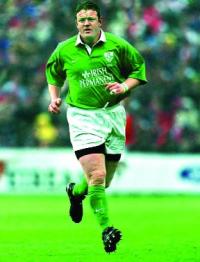

Dick Spring

Following Tralee’s defeat in the Munster Cup in early 1902, O’Sullivan, with unmistakable glee, inserted a mock obituary into his column, stating that the Tralee rugby team had succumbed and ‘died . . . after an hour’s painful illness. Regretted by a large circle of shoneens—RIP’. The patrons of rugby in Kerry, lacking the countywide organisation of the local GAA and without a voice in the increasingly nationalist popular media, could not hope to fight off such determined attacks on its status. Rugby followers found it impossible to defend the sport against the charge that it was another extension of the ‘British garrison’ in Ireland. The game was unable to win the battle for the minds of an increasingly nationalistic local population. In a final triumph to O’Sullivan’s crusade, at the annual convention in January 1905 a large majority of delegates decided to enforce from 1 February a rule suspending for two years members caught playing soccer, rugby and other ‘foreign games’.

Thanks in large part to the press and administrative campaigns of O’Sullivan, the GAA was in a position to annex Kerry’s sporting heritage. On 15 October 1905 Kerry won its first all-Ireland football title, after an epic three-match saga with Kildare. The games smashed all previous attendance records and captured the imagination of the Irish sporting public, going a long way towards securing the leading position of the GAA in Ireland’s sporting psyche. The foundation stone of the Kerry tradition in Gaelic football was laid. Rugby, condemned because of its origins in this new ‘Irish Ireland’, found little support. Among the nationalist press inKerry the reporting of the game virtually ceased after late 1902. Rugby quietly slipped into the shadows of Kerry’s sporting history.

Mick Galwey—three of Kerry’s most famous rugby exponents—all had notable careers in Gaelic games. (Sporting Heroes)

Yet rugby always retained a following in the county, although the GAA’s overbearing influence on sport in Kerry can be seen in the sporting careers of three of the county’s most famous rugby exponents. Dick Spring, who won seven Irish caps, played hurling with Kilflynn’s Crotta O’Neils and football with Tralee’s Kerins O’Rahilly in the 1970s. Mick Galwey, of Munster and Ireland fame, won a senior all-Ireland medal with Kerry in 1986. And the legendary Moss Keane won three Sigerson Cups with UCC before going on to forge a distinctive rugby career with Ireland. HI

Richard McElligott is a Ph.D student in the School of History and Archives at University College Dublin.

Further reading:

P. Foley, Kerry’s football story (Tralee, 1945).

T. Hunt, ‘The GAA: social structure and associated clubs’, in M. Cronin, W. Murphy & P. Rouse (eds), The Gaelic Athletic Association 1884–2009 (Dublin, 2009).

T.F. O’Sullivan, Story of the GAA (Dublin, 1916).