Yeats, Henry and the western idyll

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 2 (Summer 2003), Volume 11

Jack B. Yeats’s The man from Aranmore (1905) accompanied John Millington Synge’s articles on the west of Ireland for the Manchester Guardian. The islandman stands on the quayside of a small harbour on Inishmí³r (Yeats uses the name Aranmore), the largest of the Aran Islands, with the mast of his hooker appearing above the pier. The image has been painted in a clear narrative manner, portraying the type of western genre figure that became particularly associated with Yeats. (National Gallery of Ireland and the artist’s estate)

For many people the works of Jack B. Yeats, Paul Henry and their contemporaries are evocative of a simple, uncomplicated lifestyle associated with the west of Ireland. While Yeats developed as the major artist of the early twentieth century, Henry emerged as Ireland’s leading landscape painter. It was largely Henry’s vision of the west that led to a distinctive school of landscape painting, and while some of these painters, including Seán Keating and Maurice MacGonigal, were nationalistic in outlook, others, such as Charles Lamb, James Humbert Craig and later Gerard Dillon, were apolitical. They had in common a desire to use west-of-Ireland imagery to articulate a new vision of national consciousness. This view of ‘national art’, with which Henry’s work emphasising life in the west of Ireland became synonymous, was easily identified with a visual code of unspoiled landscape and people engaged in rural life. How did Yeats, Henry and others, at the turn of the last century, create a body of work from which a new rural image of Ireland emerged?

The training of Irish artists

During the eighteenth century Irish art was greatly influenced by trends in England, for obvious political and social reasons. Irish artists also turned to Italy, which was important in the training and development of their careers. This influence continued well into the nineteenth century at a time when there was growth and development in issues of identity and national consciousness in Ireland. From the mid-nineteenth century, in the search for new influences Irish artists were less interested in London and more attracted to centres such as Antwerp and Paris. France gained increasing significance because of emerging trends in Realism and Naturalism, Impressionism and Post-impressionism. In the late nineteenth century Irish artists studied at local schools such as the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art and the Royal Hibernian Academy, following which they went to the Continent to complete their training. By this time Impressionism, which had evolved in France during the 1860s and ’70s, had become a major influence. Impressionist artists such as Monet and Renoir were interested in illustrating events from real life and wished to capture the immediacy of a scene by using a brighter palette and employing varieties of painting techniques. By the end of the century many Irish artists, including Paul Henry, John Lavery, William Leech, Charles Lamb, Mainie Jellett, Evie Hone and Maurice MacGonigal, had been influenced by Impressionism.

While these Irish artists were striving to find a new way to articulate a growing sense of national consciousness, there was great political unrest and change in Ireland. The turn of the century had seen the development of the Home Rule movement, but events were rapidly to shift in a different direction. Following the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, a period of political turmoil ensued, with the War of Independence (1919–21), the Civil War (1922–3) and the creation of two states, north and south. The first two decades after independence saw Irish artists grappling with new ideas and trends in art, in the same way that poets and writers were moving towards new ways of articulating their thoughts about a changing society, in an attempt to give a distinctive expression to the Irish landscape and the Irish way of life.

The attraction of life in the west of Ireland

The appeal of life in the west to the painter Jack B. Yeats (1871–1957) and his brother, the poet and dramatist William Butler Yeats, was crucial. While Jack B. Yeats was London-born, he spent his boyhood in Sligo with his grandparents (who were millers and both owned and sailed ships). The influence of these early years remained with him all his life. Following training at art schools in London, Yeats established himself as an illustrator for journals and publications, his early style being distinguished by a strong sense of line and composition.

Seán Keating’s Seascape with figures reflects his preoccupation with Aran Islanders, seeing in them a simple dignified people with links to an earlier era in Irish history. It was the stained-glass artist Harry Clarke who encouraged Keating to go to the Aran Islands. After his first visit in 1914, he became fascinated by the people, their language and harsh lifestyle. (National Gallery of Ireland and the artist’s estate)

He married fellow art student Mary Cottenham White in 1894, the couple settling in Devon. Yeats at first painted the west of Ireland from afar before the first of a series of trips there in 1898; over the following years he held a number of exhibitions, entitled Sketches of life in the west of Ireland, in London and Dublin, in which his strong, dark western figures began to appear. In June 1905 he toured the poorest Irish-speaking parts of west Galway and Mayo, providing illustrations for John Millington Synge’s articles for the Manchester Guardian. Synge wrote twelve articles and Yeats provided fifteen illustrations; his watercolours, such as The Man from Aranmore, 1905 (p.28), provided visual imagery for Synge’s writings. Yeats also illustrated Synge’s book The Aran Islands (1907) and was consulted by Synge about the costumes for The Playboy of the Western World.

Yeats and his wife moved to Ireland in 1910. While not politically active, political events interested him and he was keenly aware of the growing sense of national consciousness. Remaining detached but not unaffected, he managed to convey many of the major events in Irish history during the struggle for independence in paintings such as The funeral of Harry Boland, Communicating with prisoners and Island funeral. Much of his early work, which was recorded on trips to the west of Ireland and executed in a clearly outlined descriptive, narrative manner, articulated his desire to find a distinctive expression for the Irish way of life. It was, however, his late great expressive works, in which he employed primary colours and vivid brushwork, that gained him an international reputation leading to his emergence as the most prominent figure in Irish art in the early twentieth century.

Henry’s first visit to the west of Ireland was to Achill Island, Co. Mayo, in 1910, and this became the defining point in his career. Paul Henry (1876–1958) came from Belfast; after training at the School of Art, he had gone to study in Paris in 1898. There he was initially drawn to Millet and the plein-air painters of the Barbizon school, until he discovered Impressionism with its brighter palette and fresh immediate scenes, as in the works of Monet and Renoir. He chose to train under the American painter James McNeill Whistler, from whom he learned to modulate close tonal relationships and to pay more attention to the abstract elements in his compositions.

![Charles Lamb's Loch an Mhuilinn [The Mill Lake] (c. 1930) depicts a small lake in Carraroe where the artist used to fish from his boat. This is a fine example of Lamb's attempt to convey the dignity that he respected in the daily lives of the hard-working Connemara people. Uniquely among western painters, he spent his life in Connemara.](/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/33.jpg)

Charles Lamb’s Loch an Mhuilinn [The Mill Lake] (c. 1930) depicts a small lake in Carraroe where the artist used to fish from his boat. This is a fine example of Lamb’s attempt to convey the dignity that he respected in the daily lives of the hard-working Connemara people. Uniquely among western painters, he spent his life in Connemara.

It was largely Henry’s vision that led to the development of a school of western landscape painting, and in the early troubled years of the twentieth century it was his imagery that inspired a view of Irish identity that became recognised both in Ireland and overseas—unspoilt landscapes with stone walls, thatched cottages and people engaged in rural life. Paul Henry and contemporaries such as Charles Lamb, Seán Keating, Maurice MacGonigal and Harry Kernoff were seen to present a coherent image of rural Ireland, which was promoted by successive Irish governments, at home and abroad.

Another artist for whom the west was to become hugely significant was the Limerick-born painter Seán Keating (1889–1977). He was trained at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art by William Orpen, who between 1902 and 1914 provided a solid grounding in life drawing and academic painting for a generation of Irish artists, including Keating, Margaret Clarke, Leo Whelan, Patrick Tuohy and James Sleator. Keating, Orpen’s main protégé, went on to become an outstanding academic draughtsman. The key event in his career was a visit to Aran in 1914, at the suggestion of the stained-glass artist Harry Clarke; he found the stony landscape and the rugged people of the islands a revelation. One result of the visit was his use of western hero-type figures in many of his works, such as The men of the west (HI Spring 1997, cover), to make powerful statements about nationalism. Years later he would become disillusioned by the divisions caused by the Civil War, but by then he had thrown his energies into recording the state’s plans for a modern, industrialised society, in particular the Shannon scheme (HI Autumn 1997, cover & p.45). His lifelong preoccupation with the west can be seen in a later work, Seascape with figures (p.29), in which the Aran Islanders’ independent lifestyle is emphasised by the lone figure of the woman on the right of the painting who gazes towards mainland Galway on the horizon. Gradually, over time, the rugged people of Aran, who etched a living from the rocky islands as well as the Atlantic Ocean, became immortalised as west of Ireland types in the work of western poets, writers and painters such as Keating, Yeats and Henry, symbolising the image of a hard-working, independent, unrom-antic race that would help to form a new nation.

Distinctive school of landscape painting

As a result of the influence of Yeats and Henry, a school of landscape and genre painters gradually emerged, largely united in their desire to give expression to the growing sense of national consciousness. This can be seen in the work of the Portadown-born painter Charles Lamb (1893–1964), whose search for rural Ireland led him to Connemara. Following his training at the School of Art in Belfast and later at the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, Lamb settled in the 1920s in the Irish-speaking district of Carraroe. Loch a Mhuilinn, c. 1930 (p.30), was painted from the artist’s boat on a small lake in Carraroe. Having come from a northern industrial town, the artist was captivated by the unspoiled landscape, clear light and ever-changing skies of Connemara. Although the woman washing presents a picturesque image, Lamb’s real interest lay in illustrating the harsh lifestyle of these western people.

Maurice MacGonigal’s Early morning Connemara (c. 1965) looks out on Mannin Bay, where the artist spent a lot of time in the 1960s, and shows his ability to use a rapid technique of painting to capture the immediacy of the scene.

This desire to give expression to the distinctive Irish landscape was echoed in the work of Maurice MacGonigal (1900–79), the son of a Sligo-born painter and decorator. MacGonigal spent many years teaching at the National College of Art in Dublin, while holidays were spent painting in the west of Ireland. Early morning Connemara, c. 1965 (p.31), is a late work by the artist, who maintained that, despite living in Dublin, the west provided the major source of inspiration for his work. His death in 1979 appeared to bring to an end the era of artists influenced by Orpen who were significant in forging a sense of identity for independent Ireland.

The new nation develops mid-century

The publication of an Official Handbook (Saorstat Éireann) in 1932 provided an informative indicator of how Ireland was developing during this period, featuring realistic yet optimistic articles on all aspects of Irish life while describing the philosophy of the Irish Free State. Edited by Bulmer Hobson, it was lavishly illustrated by many of the artists associated with creating a new image of Ireland, such as Paul Henry, Seán Keating, Maurice MacGonigal, Seán O’Sullivan and Harry Kernoff. In the general election of 1932 Fianna Fáil under Éamon de Valera formed a new government, and a new constitution was adopted in 1937. De Valera essentially saw Ireland as a rural community whose values were similar to those of the west of Ireland. While his policy of actively promoting the Irish language as an everyday medium of speech failed, it proved a strong agent for change. Up to the late 1930s the country was inward-looking in its affairs, but this changed with the outbreak of the Second World War, after which the practical issue of economic growth became the new imperative. But the 1950s saw a steady rise in emigration, with people leaving the countryside for the towns and cities and abroad. The situation was different in Northern Ireland during the Second World War, when the economy improved. Belfast and other northern towns, however, suffered greatly from severe German bombing raids. In 1949 Ireland was declared an independent republic, and just six years later it joined the United Nations.

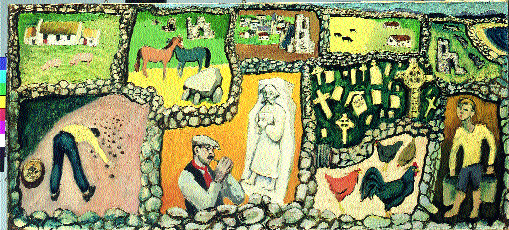

Gerard Dillon’s Little green fields (1945) is a superb example of his ability to weave the pattern of life both past and present into the landscape of Connemara. Dillon is one of many artists from Northern Ireland who fell in love with the west. He was interested in the people and the pattern of western life, such as religious processions, weddings and tinkers fighting, just as he was fascinated by the rugged landscape. (National Gallery of Ireland and the artist’s estate)

It is notable that many of the artists who were drawn to the west were from Northern Ireland. The Belfast-born artist Gerard Dillon (1916–71) settled for a time on Inishlacken, a small island beyond Roundstone, periodically visiting the Aran Islands. Like other northern artists he was attracted by the unspoiled landscape, the shy, courteous people, and the particular atmosphere and western light, which represented for him such a contrast to grey city life. It was there that he painted Little green fields, 1945 (p.32), a simple composition that belies the complexity of its content, in which the past and the present are fused in a series of images within a western field pattern.

Issues of national identity

One of the motivating forces behind Irish art in the 1920s and ’30s was an ongoing quest for national identity and for a distinct school of Irish art. This search for a national imagery had its origins in the nineteenth century, at a time when Ireland was moving towards an attempt to take charge of its own destiny. It is significant that during the Literary Revival at the end of the century poets and playwrights such as George Russell, W.B. Yeats, Lady Gregory and J.M. Synge looked towards native themes for inspiration, because they were considered important to those involved in Irish cultural life. While the aims of the Literary Renaissance were being fulfilled in the new century, Irish artists interested in articulating a new sense of national consciousness moved more slowly and proved to be a more disparate group. Issues of national identity and what constituted an Irish school of painting did emerge in the work of several artists, primarily Jack B. Yeats and Paul Henry. It was Henry’s vision of the west that was largely instrumental in forging a distinctive school of landscape painting; his imagery provided a view of rural Ireland that became recognised nationally and internationally. As a result, the west of Ireland became a source of inspiration for writers and politicians, who found in the people and landscape a body of material from which they could forge a new, distinctive construct of national identity.

A rural utopia in the west of Ireland?

What was the reality of the western idyll? Undoubtedly Irish artists were attracted to the simple life of Connemara, in the same way that French painters sought inspiration from the primitive lifestyle and countryside of Brittany and English artists turned to the unspoiled landscape of Cornwall. Part of the reason for the simple lifestyle, however, was that, being ‘west of the Shannon’, the people were largely removed from progress and from political turmoil through lack of resources and distance from Dublin respectively. Life in Connemara was hard during the 1920s and ’30s; most people lived an impoverished existence, with large families surviving on small holdings by farming or fishing. While many people spoke Irish and dressed in peasant costume, they looked gaunt because they were tired by the struggle to survive, the only alternative being emigration. They did provide their own entertainment in the form of storytelling, dancing and music, and were careful to pass their local customs and traditions from one generation to the next. When artists came to visit Connemara, they were struck by the unspoiled landscape, lifestyle and customs of the people and perceived these to reflect an earlier phase in Ireland’s history. As the new nation began to emerge in the 1920s and ’30s, imagery associated with the west became important as a way of retaining a feeling of connection with the past.

The development of Modernism

When Paul Henry moved to Dublin in 1919, he found Irish artists working within an art world that was traditional and conservative. The pattern of change, however, emerged through Irish artists such as Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone, who had studied in France and learned about developments in Cubism, Fauvism, Abstraction and some of the ideas of Modernism. While Evie Hone found her true métier in stained glass, Mainie Jellett continued with the colourful Cubism of her youth, influenced in later years by western imagery in works such as Achill horses, 1941, a picture that emerged as a result of sketching trips in the west of Ireland. These younger artists looked for new outlets to exhibit their paintings.

In 1920 Henry and his wife Grace, together with Jack B. Yeats, Letitia Hamilton, Mary Swanzy and some contemporaries, set up the Dublin Painters Society, their aim being to provide a venue where younger artists, who were excluded from the official exhibitions, could show their work. The first exhibition of members’ work was held in 7 St Stephen’s Green; after the show, Harry Clarke, Charles Lamb and Mainie Jellett joined, bringing the membership to a total of ten. From 1920 onwards the Society came to represent the best of avant-garde painting in Ireland, encouraging experimentation and the development of new ideas.

At the time Mainie Jellett painted Achill horses (1941) she was commissioned by the Irish government to create designs for the Irish Pavilion at the World Fair in New York. Largely associated with Evie Hone in bringing Modernism to Ireland in the early 1920s, Jellett sought inspiration in the west and produced some wonderful works interpreting animals and other images using her early colourful Cubist style. (National Gallery of Ireland and the artist’s estate)

This continued up to 1943, when the Irish Exhibition of Living Art became the leading venue for progressive painting. So it was at the Dublin Painters, in 1923, that Mainie Jellett showed her first Cubist and abstract pictures, a pattern that was rapidly followed by other artists who wished to exhibit new developments in art.

Meanwhile, the government continued to promote western images created by artists such as Paul Henry and his contemporaries as a way of illustrating a determined new rural nation. In the final analysis, Modernism would overtake what became outdated traditional western imagery, and with the advent of new generations of artists a new image and sense of Ireland would gradually emerge. This process of exploring identity and what constitutes the ‘Irishness’ of Irish landscape, together with what is unique about the west of Ireland, is still being actively pursued a century later, both in Ireland and by Irish artists overseas, in many of the same art forms, in addition to new media.

Marie Bourke is Keeper and Head of Education at the National Gallery of Ireland.

Further reading:

M. Bourke and S. Bhreathnach Lynch, Discover Irish art (Dublin, 1999).

A. Crookshank and the Knight of Glin, Ireland’s painters (Yale, New Haven & London, 2002).

S. Brian Kennedy, Paul Henry (Yale, New Haven & London, 2003).

H. Pyle, Yeats: portrait of an artistic family (Dublin, 1997).