‘Workers to the rescue’:Workers’ International Relief in Ireland, 1925

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2011), Volume 19

Teelin Harbour, Co. Donegal (near Slieve League)—in 1925 one of the ‘congested districts’ affected by a combination of crop failure, waterlogged turf and a crisis in the fishing industry. (NLI)

In the early years of independence, the new Irish Free State was faced with soaring poverty rates along the western seaboard. The post-war economic slump hit the cottage industries hard and forced most of those who relied on the linen trade to make a living off the land. A wet summer in 1924 caused widespread poverty in early 1925, as crops failed and turf lay soaking in the bogs. The fishing industry also took a hit, owing to an inability to upgrade equipment and to incursions into Irish waters by large foreign trawlers. The residents of the affected areas were left without suficient food or the resources to buy proper winter clothing. Many of them were freezing without the turf needed to heat their homes.

Claims of ‘famine’ rejected by the government

The English press began referring to the poverty in the west as a ‘famine’, which many in Ireland, not least the government, claimed was a campaign to damage the image of the new state. The minister for lands and agriculture, Patrick Hogan, claimed that 1925 was no different from any other year in the ‘congested districts’, but that there were small pockets of extreme poverty that the government was dealing with. He was backed by all parties in the Dáil when he rejected any notion of widespread poverty or famine and actually claimed that the potato harvest in Donegal was ‘better than the average crop for the last ten years’.

The government responded to the potato and turf failure by providing work schemes worth £170,000. In addition, the state provided £30,000 worth of potato seed and a similar amount of timber and coal as turf substitutes. Hogan claimed that the potato crop failed because of the small farmers’ insistence, against government advice, on using the Champion and Irish Queens varieties of potato. The seed distributed was of Kerr’s Pinks and Arran Victory, which Hogan claimed would prevent a future failure. The government also provided £3,000 to feed schoolchildren and set up a committee to oversee the work of charitable groups working in the affected areas.

Some of the charitable groups working in the directly affected areas gave a more human picture of events. The Emergency Relief Committee in Dublin received a letter from the staff of a school in Meenacross, Donegal, where most of the children had no food for lunch and unsuitable winter clothes and shoes. The teachers appealed to the charities to come to the area and provide food and clothing for the children. A Lady Dudley, a nurse in Kiltimagh, Co. Mayo, claimed that she had not seen a proper fire in any house she visited. In the same area an elderly woman died from severe cold. She had no fuel and in desperation went to bed in the middle of the day in a bid to stay warm. Neighbours found her dead after they went to offer her an evening meal. A six-year-old girl also died from pneumonia. The girl’s mother had no food to give the child and the rain was coming in through the roof. It was cases like this that the government measures could sometimes pass over.

Helen Crawfurd in Germany in 1922. As WIR secretary in 1925 she toured Donegal with fellow Scot and Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) member Bob Stewart.

International solidarity

Helen Crawfurd in Germany in 1922. As WIR secretary in 1925 she toured Donegal with fellow Scot and Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) member Bob Stewart.

The British section of Workers’ International Relief (WIR) set itself up in Unity Hall, Dublin, and immediately dispatched food to affected areas and set up workers’ committees. Helen Crawfurd, WIR secretary, toured Donegal with fellow Scot and Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) member Bob Stewart. Unity Hall was also the headquarters of Jim Larkin’s Workers’ Union of Ireland (WUI), and the union provided a car for the WIR delegates to travel to Donegal.

On their return they declared a famine. In reference to the government’s claim that things were no worse than normal in most places, Bob Stewart said:

‘If the conditions which I saw in West Donegal, at Kilcar and Teelin, which are no better and no worse than hundreds of such villages, are normal or approaching to normal, then a crime has been permitted which should make every responsible public body and representative in Ireland wear sackcloth and ashes for ever.’

Famine was too strong a word to use, but poverty and distress were acute in the west, and especially in parts of Donegal and Mayo, during 1925. WIR did a lot of commendable work by sending food and clothing to the worst-hit areas. An Irish branch of WIR was quickly founded (see sidebar) and continued to coordinate efforts at relief.

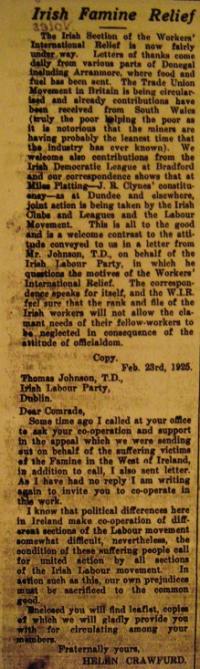

Helen Crawfurd’s appeal, published in Larkin’s Irish Worker, to Irish Labour Party leader Thomas Johnson (left) to join WIR in its relief work. Johnson refused, comparing its activity to the ‘souperism’ of Famine times.

Helen Crawfurd’s appeal, published in Larkin’s Irish Worker, to Irish Labour Party leader Thomas Johnson (left) to join WIR in its relief work. Johnson refused, comparing its activity to the ‘souperism’ of Famine times.

WIR received many financial contributions, the majority of which came from England, Scotland and Wales. Private individuals, cooperatives, local labour groups and students’ unions made considerable efforts to raise money for those starving in Ireland.

The hand of the Communist International (Comintern) was at work here in a few ways. Jim Larkin was the Comintern’s big hope in Ireland in the mid-1920s. It was thought that Larkin would establish an Irish communist party and bring his supporters with him. Larkin set up the Irish Worker League in 1924 and affiliated to the Comintern, but his laxity of approach in turning this group into a proper party began to worry those on the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI).

In an effort to get things moving, Bob Stewart was sent to Ireland to assist Larkin in setting up the party. He was also charged, however, with establishing ‘united front’ groups, one of which was WIR. Stewart sat on the committee of the British section of WIR and suggested using it to help those starving in the west. WIR succeeded in attracting republicans, but the task of bringing the official labour movement on board proved much more difficult.

Accusations of communist souperism

Helen Crawfurd appealed to the leader of the Labour Party, Thomas Johnson, to join WIR in its relief work. In a letter to Johnson she suggested ignoring political differences in order to help the people of the west. Johnson’s reply was less than sanguine. He wondered ‘whether the [WIR] committee’s actions arise from humanitarian impulses or in pursuance of propagandist effort’, and compared the actions of WIR to those of sectarian proselytisers who, in the past, provided soup to the hungry, ‘which is the first step in an insidious propaganda—to fill the bellies of the hungry being thought the best way to approach their minds’. The executive of the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress later suggested that any funds for Ireland should be distributed by them alone.

As a result of the bitter split between Larkin and the Labour Party (see sidebar), Labour would reject any group affiliated to Larkin. He had fervently attacked the Labour Party since his return to Ireland and used his newspaper, the Irish Worker, to attack the Labour leadership at every opportunity. In June 1923 the paper referred to the Labour leaders as ‘more unscrupulous, more cunning and more oppressive than any capitalist or feudal class the world has ever been cursed with’. While the communist links of WIR concerned the Labour Party, its connection with Larkin provided the real sticking point. Johnson refused to accept their espousal of worker solidarity when Larkin provided WIR with their headquarters.

Labour Party supported status quo

Crawfurd, however, replied to Johnson in a conciliatory fashion and again asked that Labour join them on a relief committee, a request that was again refused. She emphasised the independence of WIR from Larkin’s union. It is notable that it was Crawfurd, and no one from the WUI or other Irish groups, who made the appeal to Johnson. The Labour Party’s response to the crisis reflected the policy of the party at the time. Under Johnson’s leadership, the party had entered the Free State parliament and effectively accepted the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Johnson, a strict constitutionalist, wanted to help consolidate the new Free State. While critical of the government on many issues, the party did not question the constitutional status of the state for fear it

would weaken its foundations.

In response to reports of famine in the west, government supporters claimed that the British press sought to denigrate the fledgling Free State. The Labour Party, true to form, completely backed the government in its response to the crisis. Johnson told Crawfurd that the government’s work schemes and fuel supplements had averted the worst of the problems. He took credit from the fact that his party had asked the government to look into the crisis. This was the line coming from the leader of a supposedly left-wing opposition that had little representation among those worst affected by the poverty. As on many other occasions, Johnson chose to provide the government with a crutch rather than try to win the working-class vote in a time of crisis.

Irish Labour Party leader Thomas Johnson

The severe poverty in the west was at its worst in 1925 owing to the failure of the potato crop and the lack of turf. In the following years the winters were less severe but poverty continued to cause serious problems. From 1926 onwards, the major difficulty for inhabitants of the western seaboard was the inability to pay land annuities, which had to be collected by the Free State and paid to the British government every year. Peadar O’Donnell began a campaign for non-payment, with initial success in the poorest areas. The idea of withholding the annuities would later become a central plank of Fianna Fáil electoral strategy.

WIR continued after 1925 as one of a number of communist ‘united front’ groups operating in Ireland. These groups fostered relations between Irish communists and leftist republicans throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. Many of them were placed under government proscription during a ‘red scare’ in 1931. Bob Stewart failed in his bid to have Larkin form a communist party but continued to have links with Irish communism. By 1929 the Comintern had lost patience with Larkin and began concentrating on working with republicans through the ‘united fronts’. WIR, as it did elsewhere in the world, worked on a humanitarian basis but it had another agenda. The Comintern believed that it could effect unity in the Irish working class through WIR’s charitable work, but the extent of the bitterness and division within the leadership of the Irish left made this impossible. HI

Adrian Grant tutors in Irish politics at the University of Ulster, Magee College.

![Bob Stewart (with moustache) and Peadar O’Donnell (middle) with the Irish delegation of the Congress of Peasants’ International (Krestintern), Berlin, March 1930. According to Stewart, ‘If the conditions which I saw in West Donegal, at Kilcar and Teelin [in 1925] . . . are normal or approaching to normal, then a crime has been permitted’.](/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/83_small_1295622822.jpg)

Bob Stewart (with moustache) and Peadar O’Donnell (middle) with the Irish delegation of the Congress of Peasants’ International (Krestintern), Berlin, March 1930. According to Stewart, ‘If the conditions which I saw in West Donegal, at Kilcar and Teelin [in 1925] . . . are normal or approaching to normal, then a crime has been permitted’.

C. Breathnach, The Congested Districts Boards of Ireland, 1891–1923: poverty and development in the west of Ireland (Dublin, 2005).

E. O’Connor, Reds and the Green: Ireland, Russia and the Communist Internationals, 1919–43 (Dublin, 2004).

N. Puirséil, The Irish Labour Party, 1922–73 (Dublin, 2007).