Wordsworth in Ireland

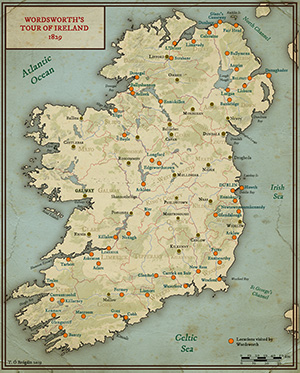

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2020), Volume 28In late August 1829, the English poet William Wordsworth (1770–1850) crossed the Irish Sea for the first time, sailing from Holyhead to Howth.

By Brandon C. Yen

Wordsworth spent five weeks in Ireland, visiting glens, rivers, loughs, abbeys, churches, castles and demesnes, as well as Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Derry and Belfast, before returning to Britain via Donaghadee in County Down. His travelling companions were John Marshall (MP for Yorkshire) and Marshall’s son James. With these wealthy flax-spinners from Leeds, Wordsworth toured the island in a ‘carriage and four’. Along the way, he kept up with friends such as Caesar Otway and William Rowan Hamilton, and made new acquaintances, clerical, political and literary, such as the Edgeworth family in County Longford. Remarkably, the 59-year-old poet also climbed Carrauntoohil with the young James Marshall.

Above: Fair Head, Co. Antrim—a pair of eagles soaring above its cliffs was the only image of Wordworth’s 1829 trip to Ireland that made it into his poetry. (NLI)

In the event, only one image made it into Wordsworth’s poetry: a pair of eagles soaring above the cliffs of Fair Head in County Antrim. Nonetheless, there were much deeper, much more interesting and illuminating connections. They tell us about the poet’s engagement with crucial socio-political issues and, at a more intimate level, about the cultural exchanges between Ireland and Britain in the early nineteenth century.

‘Erin’s coast’

Ireland rarely appears in Wordsworth’s poetry. One instance is his ‘View from the Top of Black Comb’, composed in 1813. There, he regards Black Combe as the seat of a ‘ministering Angel’. From this Cumbrian mountain,

‘… the amplest range

Of unobstructed prospect may be seen

That British ground commands …’

This prospect view encompasses English, Scottish and Welsh hills and rivers, together with the Isle of Man and—apparently beyond the Irish Sea—an ‘azure Ridge’:

‘Yon azure Ridge,

Is it a perishable cloud? Or there

Do we behold the frame of Erin’s Coast?’

As Wordsworth notes in his Guide to the Lakes, Ireland can indeed be seen from Black Combe, but Ireland’s presence is ambiguous in the view that the mountain affords of ‘British ground’. In describing ‘Erin’s coast’ as ‘the bright confines of another world’, Wordsworth alludes to Milton’s Paradise Lost, where Beelzebub imagines occupying the newly created world: from there, the fallen angels might regain heaven’s ‘bright confines’. The allusion implies a wish to incorporate ‘Erin’ into a unitary sense of nationhood (the Act of Union had come into effect in 1801), and yet this wish is mixed, perhaps unconsciously, with the ambivalences of an outsider. These ambivalences underlay Wordsworth’s responses to Irish landscapes and people in 1829.

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

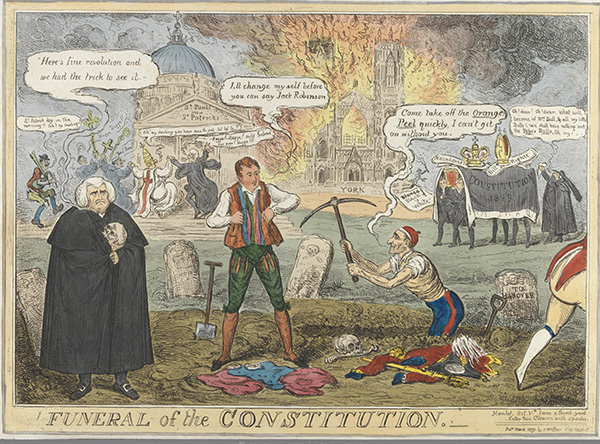

1829 was the year of Catholic Emancipation, which received the royal assent on 13 April after a prolonged struggle. Wordsworth was against it. In March 1829, half a year before his Irish journey, he wrote to Charles Blomfield, bishop of London, describing Catholicism as a ‘soul-degrading faith’, and Irish Catholics as ‘swarms of degraded people’. In calmer moments, Wordsworth’s views of Catholicism were more ambiguous. In 1822 he had published Ecclesiastical Sketches, a sequence of sonnets tracing the origins, development and progress of the church in England. One sonnet glances critically at Henry VIII’s ‘reckless mastery’ following his break with Roman Catholicism, acknowledging that the Henrician Reformation swept away both good and evil. There, however, Wordsworth also alludes to Paradise Lost in mocking those Catholic trappings that, in his opinion, mislead believers. Milton vividly portrays how a ‘violent cross-wind’ blows ‘Eremites, and Friars / White, Black, and Grey, with all their trumpery’ to ‘The Paradise of Fools’. Borrowing from Milton, Wordsworth says that all those ‘Bulls, pardons, relics, cowls’ were not worth retaining, however much we lament the violence of the Reformation.

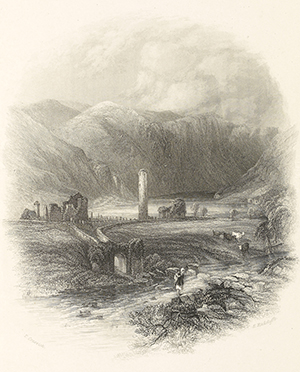

Visiting Glendalough (Co. Wicklow) on 3 September 1829, Wordsworth witnessed the influence of Catholicism. With its round tower and ‘seven churches’, Glendalough is steeped in local traditions relating to St Kevin. Thomas Moore popularised the place in one of his Irish Melodies, telling the story of St Kevin’s Bed, a precipitous spot from which the saint was said to have flung the amorous Kathleen into the lake. In Glendalough, Wordsworth saw an Irish woman who was going to dip her child in St Kevin’s Pool ‘to cure its lameness’. The ‘tenderness’, he wrote, with which the Catholic woman ‘spoke of the Child and its sufferings and the sad pleasure with which she detailed the progress it had made towards recovery would have moved the most insensible’. The woman’s religion, however, precluded Wordsworth’s full sympathy. He asked: ‘What would one not give to see among protestants such devout reliance on the mercy of their Creator, so much resignation, so much piety—so much simplicity and singleness of mind, purged of the accompanying Superstitions?’

Killarney

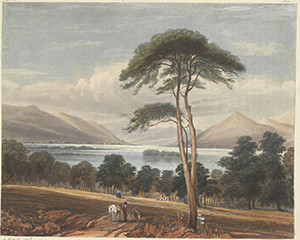

Notwithstanding his reservations about Catholic superstitions, Wordsworth relished Irish landscapes. Like the Wicklow Mountains, Killarney was a favourite destination for English tourists. Its beautiful lakes were often compared with their English counterparts. Before his 1829 journey, Wordsworth had written a playful poem about fashionable tourists in the English Lake District. He had seen these words in the visitors’ book at the viewing station on Lake Windermere: ‘Lord & Lady Darlington, Lady Vane, Miss Taylor & Capn Stamp pronounce this Lake superior to Lac de Geneve, Lago de Como, Lago Maggiore, L’Eau de Zurick, Loch Lomond, Loch Ketterine or the Lakes of Killarney’. Wordsworth ridiculed this remark as ‘Folly’s own Hyperbole’. He himself had visited all the Continental and Scottish lakes here dismissed by the wealthy tourists. As for Killarney, Wordsworth ‘wish’d at least to hear the blarney / Of the sly boatmen of Killarney’.

Above: ‘Funeral of the Constitution’—Isaac Cruikshank’s jaundiced view of Catholic Emancipation, with which Wordsworth would have concurred. (TCD)

Sure enough, Killarney left an abiding impression on Wordsworth. In 1841 he described Killarney in relation to the English lakes in a letter to Samuel Carter Hall, co-author (with his wife Anna Maria) of Ireland: its scenery, character, &c. (1841–3). Wordsworth told Hall that the ‘three Lakes of Killarney considered as one, as they might naturally be, lying so close to each other, were together more important than any one of our Lakes’.

Above: Glendalough, Co. Wicklow, where Wordsworth witnessed the influence of Catholicism. (NLI)

Hamilton

Wordsworth’s major contact during the 1829 tour was William Rowan Hamilton (1805–65), the young professor of astronomy at Trinity College, Dublin, and Royal Astronomer of Ireland. The two had met in the Lake District in 1827. Writing to his sister Eliza from Keswick in September 1827, Hamilton had mentioned climbing the Cumbrian fell, Helvellyn, with Alexander Nimmo (the civil engineer who designed Limerick’s Sarsfield Bridge) and Nimmo’s apprentice, Jones. Also with them was Caesar Otway, a Church of Ireland clergyman, whose Sketches in Ireland (1827) Wordsworth was to read with ‘great pleasure’ before his tour and who, together with Hamilton, was to accompany Wordsworth to Glendalough. After descending from Helvellyn, the friends went to Rydal Mount to visit Wordsworth. The poet then walked back with them, but he and Hamilton so much enjoyed each other’s company that the pair strolled back and forth between Rydal and Ambleside, a distance of some two miles, until ‘midnight’. Hamilton told his sister that ‘he and I were taking a midnight walk together for a long long time, without any companion, except the silent stars, and our own burning thoughts & words’.

Hamilton’s sister Eliza (1807–51) was herself a poet. Visiting the Lake District with her brother in 1830, she spent a morning discussing poetry with Wordsworth in the summer-house in Rydal Mount’s garden. Amongst her manuscripts (now kept at Trinity College, Dublin) are two sonnets addressed to Wordsworth, composed in the early 1840s. In 1830 she had left a poem in Wordsworth’s daughter Dora’s album, beginning ‘It is not now that I can speak’. Ten years on, with the giddiness of joy having settled into calm reflection, Eliza Hamilton endeavoured to ‘speak’ but was conscious of her lack of poetic power. The poem looks back on the 1830 visit, when

‘Life was one sea of glory o’er whose breast

Glided entranced thy young enthusiast guest.’

The memories of Wordsworth’s ‘melodious home’ are still vivid, but she is afraid of disturbing the older poet with too ardent feelings and is aware that she cannot convey ‘half of all that lives’ in her heart.

William Rowan Hamilton devoted himself to mathematics but never ceased to read and write poetry. In 1829 he was arguing with the novelist Maria Edgeworth’s half-brother, Francis (1809–46), over the relative importance of science and poetry. Whilst Hamilton saw beauty in science, Francis Edgeworth insisted that the ‘intense unity’ in works of art could not be found in mathematics. When Wordsworth visited Hamilton at Dunsink Observatory in 1829, they discussed a passage in Wordsworth’s long poem The Excursion (1814) which ‘did not quite please [Hamilton] by its slight reverence for Science’.

In the early 1830s Hamilton again responded to Wordsworth in his introductory lectures on astronomy, delivered annually at Trinity College, Dublin. Written poetically, these lectures were attended not only by undergraduates but also by cultural figures, including the poet Felicia Hemans, who moved to Dublin permanently in 1831. The 1831 lecture contains two long passages from The Excursion, displaying a genealogy of pagan and Christian peoples who have observed nature imaginatively and Wordsworth’s view that science can and should offer support and guidance to ‘the Mind’s excursive Power’. Hamilton quoted these approvingly but shifted their bearings to underscore the importance of science. He invested science with an imaginative stature which Francis Edgeworth had refused to recognise and which Wordsworth, he thought, had inadequately acknowledged in The Excursion.

Above: ‘Lower Lake, Killarney’—Killarney left an abiding impression on Wordsworth.

Edgeworthstown

Wordsworth and the Marshalls reached Edgeworthstown, Co. Longford, on 20 September 1829 and stayed two days. There Hamilton joined them again, and they met the Edgeworths. Writing to his sister Eliza, Hamilton described how much he and Francis Edgeworth had enjoyed talking with Wordsworth. He also mentioned that Maria Edgeworth, despite her illness, had ‘exhibited in her conversations with Mr. Wordsworth a good deal of her usual brilliancy; she also engaged Mr. Marshall in some long conversations upon Ireland; and even Mr. Marshall’s son, whose talent for silence appears to be so very profound, was thawed a little on Monday evening’ (they left on Tuesday morning).

Privately, however, Maria Edgeworth criticised Wordsworth for his ‘superfluity of words’, even though she also saw ‘a vein of real humour’ under ‘all this slow, slimy, circumspect tiresome lengthiness’. She described John Marshall’s paleness and reported his spending a colossal amount of money on a recent election, though she thought that he was ‘a remarkably liberal man in all his views for Ireland’. Regarding James Marshall, ‘I charitably suspect [he had] more in him than came out’. But Edgeworth was ‘glad’ that it was ‘becoming more the fashion for English travellers to visit Ireland’.

Eagles

Wordsworth’s poem ‘On the Power of Sound’ (1835) contains the only image that arose from his Irish tour:

‘Thou too be heard, lone Eagle! freed

From snowy peak and cloud, attune

Thy hungry barkings to the hymn

Of joy …’

Written shortly after the tour, this passage was inspired by a pair of eagles he had seen at Fair Head, Co. Antrim. Wordsworth described to Francis Edgeworth how the eagles had ‘barked or yelped or clattered or screamed or whistled’: they ‘sailed towards the setting sun & were lost in a red cloud’, and then they ‘returned and spread their wings to the full width’ between the ‘sun set of corallic carmine’ and the ‘dreary’ rock.

In response, Francis Edgeworth said that the ‘barking noise’ reminded him of the Greek writer Aeschylus’s reference to the ‘Promethean Eagle’ as the ‘winged hound of Jove’; he had always understood this as meaning the prowess of the bird of prey, but now the ‘barking’—the sheer sound of it—added ‘new force’. The Irish eagles also appear in one of Wordsworth’s sonnets about an eagle cooped up in Dunollie Castle on the west coast of Scotland:

‘The last I saw

Was on the wing; stooping, he struck with awe

Man, bird, and beast; then, with a Consort paired,

From a bold headland, their loved aery’s guard,

Flew high above Atlantic waves, to draw

Light from the fountain of the setting sun.’

Brandon C. Yen is writing a book (with Peter Dale) on Wordsworth’s trees for Reaktion.

FURTHER READING

C. Connolly (ed.), Irish literature in transition, 1780–1830 (Cambridge, 2019).

S. Gill, Wordsworth: a life (Oxford, 2019).