‘Women of the pave’: prostitution in Ireland

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 3 (May/Jun 2008), News, Reviews

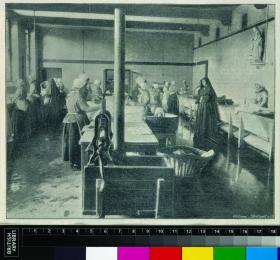

Interior of a Dublin Magdalen laundry in the 1890s. (British Library)

Thousands of women working as prostitutes roamed the streets of the towns and cities of Ireland in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While there was a common belief that prostitution was an inevitable feature of life, especially where military garrisons existed, as long as prostitutes remained out of the public eye they were tolerated. It was most often their visibility that caused anxiety in the wider public. Prostitutes were believed to be the main source of venereal disease infection, and prostitution itself was believed to be contagious. In 1809 the women prisoners confined for debt in the Four Courts Marshalsea in Dublin, fearing moral and physical contagion, complained about having to mix with ‘women of the town (some from the very flags [streets])’.

Few reliable statistics

There are few, if any, reliable statistics on the extent of prostitution. The two best sources are the police statistics for the Dublin Metropolitan District from 1838 to 1919, and the criminal and judicial statistics from 1863 (covering the entire country). The figures account for arrests and convictions of women accused of soliciting; they do not record the number of re-arrests. Since many women were arrested dozens of times within any one year, these figures do not tally with the numbers of women operating as prostitutes. They also fluctuate widely—giving the impression that prostitution is diminishing or increasing—but in a way not backed up by other evidence. On the other hand, it is unlikely that every prostitute was arrested.

So these statistics give us a general idea of where and when the police were most vigilant in arresting prostitutes. The Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) statistics show that 2,849 arrests were made in 1838, increasing yearly to a maximum of 4,784 in 1856 and decreasing to 1,672 in 1877, fluctuating around the 1,000 mark from then to the 1890s and reaching a low of 494 in 1899. In the twentieth century the highest number of arrests, consequent on the introduction of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, is in 1912, with 1,067 detentions, and then the arrest figures gradually decrease to a low of 198 by 1919. If we look at the figures for the entire country we find that in 1863 (and these figures include Dublin) there were 3,318 arrests for prostitution. Leinster consistently had the highest number of arrests, and Connacht the least. Galway City rarely features, but prostitution certainly existed there. The 1851 census listed 27 prostitutes and brothel-keepers in County Galway (four in the city) that go unrecorded in the crime statistics. In 1881, when no arrests were returned for Galway City, a policeman stationed there described a brothel in Middle Street as ‘the worst house in Ireland’.

Brothels

The DMP suggested that there were 1,630 prostitutes in Dublin in 1838; by 1890 that figure had declined to 436. A number of women worked in brothels, though they did not necessarily live in these establishments. Brothels, recorded in police statistics as of either a ‘superior’ or ‘inferior’ type, were most common in Dublin but also existed in other towns and cities. In 1842 there were 1,287 brothels in Dublin. During the Famine years the number of brothels in the city hovered between 330 and 419, with in excess of 1,300 women working from them. By 1894 there were 74 brothels operating openly in Dublin and an average of three women worked from each of them. The police were slow to close down brothels, believing that this spread the problem into new areas by dispersing the women.

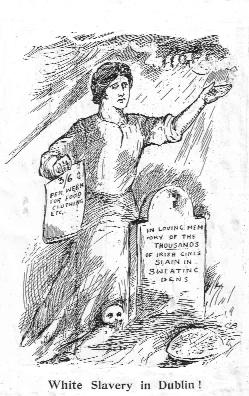

‘White Slavery in Dublin’, The Irish Worker, 25 May 1912.

Motivation

Prostitution was often the resort of the desperate in a country that offered limited opportunities to women and where a change in economic circumstances, such as the loss of employment or desertion by a spouse or breadwinner, plunged many women into economic crisis. Evidence from the Poor Inquiry of 1836 suggests that unmarried mothers who could not get the putative fathers to support them and the children were ‘in some instances driven . . . to prostitution as a mode of support’. Susanna Price took to prostitution and crime to support herself when her soldier husband was overseas. In 1840 she was sentenced to seven years’ transportation for larceny. Catherine Grady, ‘a notoriously improper character and public nuisance’, pleaded guilty to theft in Kilkenny in 1846 and was transported for seven years. The reporter commented that it was a ‘happy riddance for the city’. Bridget Hayes, who was transported for larceny in 1848, pleaded that she had been seduced by a young man who cast her off and that she ‘had to pursue a wicked life to keep herself from starvation’.

Prostitutes were most often charged with theft, being drunk and disorderly, vagrancy and sometimes murder. When convicted of soliciting the general sentence was a fine or, in default of payment, two weeks or longer in prison. In Kilkenny a prostitute who stole £200 from a farmer got six months with hard labour in 1871. The judge had little sympathy for the victim, observing that married men should not be ‘going about drinking with abandoned females’. It is also evident that many newspaper reporters used some of these court cases as a way to amuse their readers. For instance, two women who lived in a hovel in Ennis were charged with not paying their landlord rent. In evidence it emerged that both women, Fanny Crowe and Bridget Hogan, were ‘prostitutes of the most infamous character’ and considered a nuisance to the entire neighbourhood. Fanny Crowe was described as ‘a masculine looking woman with a Connacht accent’. Crowe, when asked by a solicitor if she was not a ‘quiet, mild and respectable woman’, answered, to the delight of the court, ‘I think it would be very hard for you to find a woman that you’d get the three in’.

Streets renamed

In the cities, renaming streets associated with prostitution was relatively common. Anderson’s Row in Belfast, noted as an area of immorality, became Millfield Place in December 1860, though this did not improve its reputation. In 1885 Lower Temple Street, Dublin, became Hill Street in consequence of a memorial to the Corporation from a number of inhabitants who ‘had suffered serious deterioration in the value of [their] property’ as certain houses in the lower end of the street were occupied by ‘immoral characters’. In 1888 Dublin Corporation renamed Mecklenburgh Street Tyrone Street to please the respectable working-class residents of the area.

Violence and abuse

‘White Slavery in Dublin’, The Irish Worker, 25 May 1912.

Women who worked as prostitutes left themselves open to violence and abuse. Mary Flanagan, for instance, an ‘exceedingly juvenile cyprian’, appeared before the court in Ennis in October 1845. She alleged that a client, Francis Kelly, had enticed her into a field and raped her at knifepoint over a period of three hours. Kelly was later acquitted when Flanagan refused to identify him. In Limerick, Mary Carmody, who admitted she had been a prostitute for four years, accused a young man of raping her. Her assailant, who said she was ‘a prostitute and she was bound to go with him’, told police she had taken a shilling and then told him to go to hell. Despite his claim he was convicted, as was a soldier whose excuse for raping a prostitute was that he had no money. Three men had attempted to drown a prostitute by throwing her off Pope’s Quay in Cork in 1839. A number of these women attempted suicide. Kathleen Dolan did so by jumping into the river in Galway, stating that she ‘would not put up with all the warrants and imprisonments’. A small number appear to have been committed to lunatic asylums. ‘K.D.’ was confined to Ballinasloe Asylum with ‘dementia’, having been imprisoned for attempting suicide. Ellen Byrne, a 26-year-old prostitute from Dublin, committed infanticide after being refused entry to the workhouse. Found guilty but insane, she was sent in 1893 to Dundrum Mental Hospital, where she died within the year.

Whatever their treatment by the courts or the public, prostitutes were not without some forms of resistance. It was a common practice for women to change their names to confuse the authorities. They formed a generally mobile population, migrating to towns and cities. With some groups of prostitutes there was also solidarity, seen particularly in the case of the Wrens of the Curragh. It was noted by a number of magistrates that when arrested the women were often ‘very violent, and threw themselves down and refuse to walk’. Sometimes the women committed crimes in order to go to jail and receive medical attention or a respite from their harsh life. For instance, in 1846 Mary Murphy pleaded guilty to breaking the windows of the mayor’s office in Kilkenny in order to be imprisoned.

By the end of the nineteenth century geographical limits were placed on where brothels and prostitutes might operate unhindered. Prostitutes, however, still roamed much more freely than the public or authorities wished. By the early twentieth century Irish nationalists argued that prostitution and venereal disease were symptoms of the British presence in Ireland and that it was only with Irish independence that they would disappear. Apparent rises in the rates of illegitimacy, venereal diseases and sexual crime in the 1920s suggest the simple-mindedness of that view.

Maria Luddy is Professor of Modern Irish History at the University of Warwick.

Further reading:

M. Luddy, Prostitution and Irish society, 1800–1940 (Cambridge, 2007).