Wittgenstein’s Irish cottage

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2018), Volume 26It is remarkable that three noted practitioners respectively of the arts of painting, dialectic and poetry chose a modest Connemara dwelling as their base.

By John Hayes

One of the most eminent philosophers of the twentieth century, Ludwig Wittgenstein (b. 1889 in Vienna), made several visits to Ireland. The longest of these was from November 1947 to June 1949. For four months during that time he stayed in a cottage in Rosroe, Co. Galway, a dispersed settlement of six houses set between the mouth of Killary Harbour and a sea inlet called ‘Little Killary’. ‘Quay House’, on the village pier, was owned by Myles Drury (1904–87), elder brother of a former Wittgenstein student, Maurice O’Connor Drury (1907–76). Familiarly called ‘Con’, Maurice was a psychiatrist employed by St Patrick’s Hospital, James’s Street, Dublin. Before its purchase by Myles—an Exeter architect of Irish parentage—the cottage had been a coastguard station. In Connemara: the last pool of darkness (2008), Tim Robinson states that the painter Paul Henry (1876–1974), mostly based on Achill Island in the 1910s, had been an occupant. Drury’s interest in acquiring the cottage was probably influenced by prior knowledge of the district. His aunt, Pamela Elizabeth Drury, ran an evangelical school in Salruck, Cushkillary, probably under the auspices of the Irish Church Missions to the Roman Catholics. She died in 1918, aged 76, and lies buried in the local Church of Ireland graveyard.

Above: ‘Wittgenstein’s cottage in Ireland’—in Rosroe, Co. Galway—by Peg Smythies. (Daniel Smythies)

Three years after Wittgenstein’s stay from April to August 1948, the poet Richard Murphy (1927–2018) rented the cottage for five years from Myles Drury at £20 a year. In his memoir The kick (2017), Murphy described the accommodation. Heat came from a turf fire. The fuel was stored in a galvanised shed in the backyard, where there was also a chemical toilet. Candles gave light after dark. Drinking water had to be drawn by bucket from a nearby well. The kitchen furniture was made of deal. The beds were of cast iron with horsehair mattresses.

Wittgenstein’s first visit, 1934

Wittgenstein already knew the frugality that prevailed in Rosroe. He had spent a fortnight’s vacation in the cottage in September 1934 with his partner, Francis Skinner (1912–41), and Con Drury (then a medical student at Trinity College, Dublin). Scion of one of the richest families in Austria, Wittgenstein had disclaimed his rights to a share in the vast family fortune after his return from military service in the First World War. Inspired by the teachings of Leo Tolstoy, he resolved to live as simply as possible. During military service he had managed to write the only book he published in his lifetime, known by the abbreviated title of the Tractatus (1922). This offered a final solution to questions about what is expressible in language and was widely influential. Following a period away from philosophy, he returned in 1929 to Cambridge University, where he had studied with Bertrand Russell from 1911 to 1914. He and Con Drury, who was in his third year reading for the Moral Sciences Tripos, soon became close friends—a friendship that lasted until Wittgenstein died in 1951.

In a journal published in 1981, Drury gave some information about the first Wittgenstein visit to Rosroe. Wittgenstein and Skinner travelled from Galway by train on the Clifden line. They were met by Drury at Recess and driven the remaining twenty miles to the cottage. Wittgenstein found the countryside strikingly beautiful because of its ‘marvellous’ colours, but he thought the inhabitants’ dwellings ‘even more primitive’ than he had encountered in Poland, hitherto his standard for ‘rock bottom’. As it rained continuously, the friends spent much of their vacation within walls of ‘rough whitewash texture’, reading William H. Prescott’s History of the conquest of Mexico (1843) aloud to one another. They did get some fine days, however, and took advantage of the clement weather to walk by the sea and row to the Mayo shore. On coming across a local family, the Mortimers, saving hay, Wittgenstein suggested that they retreat, as ‘it is not right that we should be holidaying in front of them’. The Mortimers augmented their family income by seasonal salmon-fishing, landing their catch on the pier in front of the Drury cottage.

Second visit, 1948

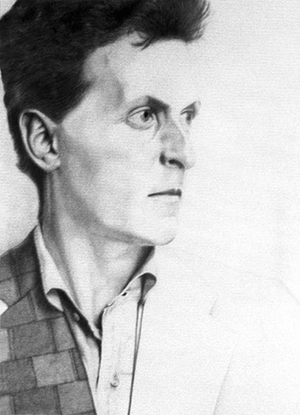

Above: Pencil drawing of Ludwig Wittgenstein by Christiaan Tonnis.

Most locals regarded Wittgenstein as eccentric and he, for his part, shunned interaction with them. He was interested in the maritime birdlife and fed several birds daily. In a poem, ‘The Philosopher and the Birds’ (1953), Richard Murphy recorded their bathetic fate: after Wittgenstein’s departure in August to visit friends and family, ‘hordes of village cats … massacred his birds’. Wittgenstein had intended to return to Rosroe for the winter. Fearful, however, that he would be unable to access medical care if he fell ill, he lodged instead in Ross’s Hotel, Parkgate Street, Dublin.

Peg Smythies and the provenence of her sketch

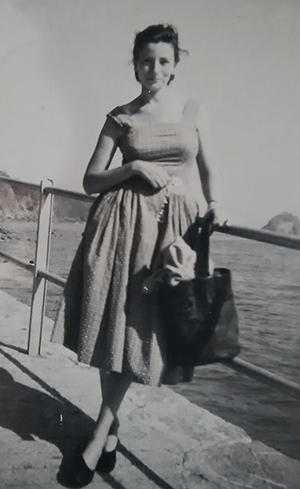

Above: The artist Peg Smythies—three of her four husbands were close friends of Wittgenstein. (Saskia Marjoram and Daniel Smythies)

A number of questions arise. First, why did Mrs Smythies make such a sketch at all? One obvious answer is that three of her four husbands were close friends of Wittgenstein. Born Margaret Britton in 1924 and trained at the Royal College of Art in Kensington, she worked both as a teacher and as a freelance designer for such purveyors of elegance as the Sandersons (wallpapers) and Charnos (lingerie) firms. In 1959 Peg married William Barrington Pink (1920–2006), who in that year took over one of three factory bays in the Shannon Free Trade Zone, established by a modernising Dr Brendan O’Regan. Pink’s project was to construct an ink-jet machine designed to mark fabric for cutting. The company failed and closed in 1961. On his return to England, Pink made major contributions to the education of special needs children, focusing on craft skills.

A decade earlier, Pink had met Wittgenstein in what was to be the last year of the philosopher’s life (1950/1). At that time he was a lodger in the Oxford home of Elizabeth Anscombe (born at Limerick’s North Strand in 1919 and later a philosopher of considerable stature). Anscombe was one of the few women whom Wittgenstein had admitted to his classes (under the rubric of an ‘honorary man’). She invited him to stay with her when he was dying from prostate cancer. Pink and Wittgenstein took walks together and had conversations of remarkable candour. Pink had the temerity to ask Wittgenstein whether his involvement in philosophy was connected with his homosexuality. He was met with the reply: ‘Certainly not’.

Above: A young Maurice ‘Con’ O’Connor Drury, whose older brother, Myles, owned the cottage. (Wittgenstein Archive, Cambridge/Michael Nedo)

Sometime after Yorick’s death in 1980, Peg married Rush Rhees (1905–89), a philosophy lecturer in Swansea. Wittgenstein appointed Rhees, Anscombe and the Finnish philosopher Georg H. von Wright as his literary executors. Rhees formed a close friendship with Con Drury, a record of which can be found in a voluminous correspondence now held in Mary Immaculate College, Limerick. He encouraged a diffident Drury to write what turned out to be the most intimate literary portrait of Wittgenstein by any of his students, ‘Conversations with Wittgenstein’, as well as a remarkable book, The danger of words (1973), casting a Wittgensteinian light on the practice of medicine, and psychiatry in particular. Peg Smythies’s acquaintance with Wittgenstein gives a context for why she might have made the sketch, although there is a further question as to whether it is representational or imaginative. A family member, Saskia Marjoram, believes that it was sketched on a visit to Rosroe, as Peg usually drew directly from life. A third question as to the dating of such a visit may only be answered with a conjecture—and I would suggest the latter half of the 1950s, with Pink as a companion.

Perched at the edge of an offshore European island, her sketch can stand as a symbol of a contrarian lifestyle. For Wittgenstein, at least, the very ‘form’ of modern culture was the siren call of ‘progress’, with its characteristic ‘sound of machinery’—a sound that quelled the silence necessary if all the potentials of the human spirit are to unfold.

Prof. John Hayes was formerly Dean of Arts, Mary Immaculate College, Limerick.

FURTHER READING

John Hayes (ed.), The selected writings of Maurice O’Connor Drury on Wittgenstein, philosophy, religion and psychiatry (London, 2017).

Brian O’Connell, Brendan O’Regan (Irish Academic Press, 2018).

Peg and Yorick Smythies, The Doves’ water barrow (Steve Ball, 1998).

‘Wittgenstein and Ireland’, in F.B. Flowers III & Ian Ground (eds), Portraits of Wittgenstein, Vol. II (London, 2016).