William Smith O’Brien in Van Dieman’s Land

Published in 1848 Rebellion, 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1998), Volume 6

William Smith O’Brien (Currier and Ives)

Not many leaders of armed rebellions in Ireland during the centuries of English rule had the opportunity to mull over their actions in later days. One who did was William Smith O’Brien, leader of the abortive Young Ireland rebellion of 1848, who spent five years, most of them on ticket-of-leave, in what was then Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania.

Background

William, son of Sir Lucius O’Brien, was born in 1803 at Dromoland Castle, County Clare. Descended from Brian Boru, the O’Briens were one of the few families of Gaelic origin to become part of the Protestant landed elite. He was educated at the great English public school of Harrow where in later times Winston Churchill was a pupil. Smith O’Brien then went on to Cambridge University. In his years of exile, when corresponding with his wife Lucy about the education of their eldest son Edward, he set his face against the youth entering the same university, where, he said ‘I learnt…much that was evil and little that was good’. He urged that his son should enter Trinity College, Dublin. O’Brien himself retained from his early associations an English accent which distanced him from his associates in Irish political life, one of whom described him as having ‘too much Smith and too little O’Brien’.

Van Dieman’s Land

He was convicted and sentenced to death for his part in the rebellion of 1848, which was in fact a fiasco. But it was high treason nonetheless. The sentence was later commuted to transportation to the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land. Earl Grey, the Colonial Secretary, had decided that the best policy in regard to the Young Ireland prisoners was to consign them to gentlemanly oblivion. Sir William Denison, the governor, would have preferred to treat them as convicts. But he was obliged to offer O’Brien a ticket-of-leave.

Initially O’Brien refused because of the condition attached which would have prevented him attempting to escape. So while his fellow-revolutionaries, Patrick O’Donohoe, Thomas Meagher and Terence MacManus, were immediately set at large, O’Brien was sent on to Maria Island, the most remote outpost of the penal settlement. An attempt at escape was bungled and he was, in August 1850, transferred to Port Arthur.

Port Arthur

The cottage in which O’Brien was housed is now one of the preserved buildings of Port Arthur Historic Site. It is a pleasant enough dwelling, pumpkin-coloured, the front rooms set back from a pillared porch and with a garden at the rear. It occupies a commanding site on a ridge positioned above the main penitentiary buildings and parade ground. Just off shore in Carnarvon Bay may be seen the Isle of the Dead, burial ground of almost 2,000 convicts as well as officials, soldiers and their wives.

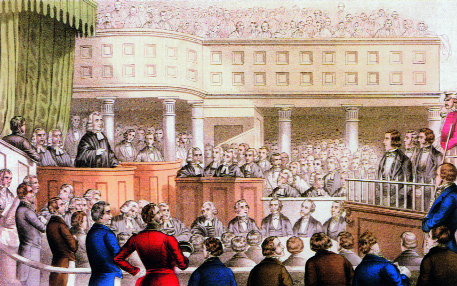

Sentence is passed on Thomas Francis Meagher, Terence B. McManus and Patrick O’Donoghue (standing in the dock to the right) at their trial at Clonmel, 22 October 1848. (Currier and Ives)

O’Brien was spared the worst horrors of convict life. His greatest hardship at Port Arthur was the isolation. But he had books, he tended the garden and started a journal for Lucy, as well as corresponding with family and friends. The journal and letters reveal him to have been a man of integrity, sensitivity and unswerving patriotism. He combined a gentleman’s sense of honour with an unshakeable conviction that the cause of his country was sacred. ‘No holier cause than that in which I was engaged ever led a patriot into the field or conducted him to the scaffold’ he wrote to his wife, who was less than enthusiastic about her husband’s politics.

Ticket-of-leave

After three months, urged on by sympathisers in Hobart, he successfully applied for a ticket-of-leave. The Young Irelanders in general benefited from the local anti-transportation and pro-representative movements of the time; local newspapers such as the Hobart Town Courier and the Launceston Examiner, described them as patriotic, if deficient in prudence. This was in marked contrast to the vitriolic outpourings of The Times of London.

O’Brien received an ovation on his arrival in Hobart but was not allowed to settle there, moving on to New Norfolk. He took lodgings in Elwin’s Hotel, now the Glen Derwent, a pleasant rural inn on the river Derwent, where he remained for two and a half years, later moving to Richmond. As a matter of government policy the Young Ireland prisoners were required to live in separate districts. Thomas Francis Meagher was at Campbell Town and Ross, John Mitchel at Nant Cottage, Bothwell.

Funds were sent from Ireland to Smith O’Brien from his Cahirmoyle estate. As was the case with most of the other transported Young Irelanders, private means alleviated the hardships of exile. During the Crown proceedings against him O’Brien had placed his estate in trust to forestall possible confiscation. But his correspondence from New Norfolk indicates that he regulated his day-to-day affairs punctiliously.

Political principles

The Young Irelanders had been inspired and heartened by the 1848 French Revolution, especially by the fact that the revolutionaries had been able to get rid of King Louis Philippe while leaving property intact. The Irish leaders thought of a middle class revolution as a bulwark against a peasant uprising, a subtlety which the British government failed to grasp. Smith O’Brien himself was no doctrinaire republican. He wrote on 20 August 1850 to T. Chisholm Anstey, an English supporter of Young Ireland:

As for personal loyalty to the sovereign, I am not aware that I have ever during the course of my life uttered a word disrespectful to the queen and though in the event of a national war between Great Britain and Ireland I should have acquiesced in the establishment of a republic as the only form of government which circumstances have permitted. Yet my political principles have never been republican and I should have much preferred to any novel experiment a restoration of the ancient constitution of Ireland: the Queen, Lords and Commons of Ireland.

Smith O’Brien’s cottage, Port Arthur, Tasmania. (C. Heaney)

Disillusioned by the inadequacy of British government policies towards Ireland during the Famine years, he simply wanted self-government under the Crown for Ireland. He had harsh things to say about the government’s policies during the Famine ‘which they have permitted if they have not caused’. Ireland, he claimed, was undergoing greater loss of life from British mismanagement of famine than might result from an Irish revolution.

Smith O’Brien’s critics, on the other hand, accused him of a total disregard of reality in expecting the people to participate in an uprising after years of starvation. It is a truism of history that successful revolutions take place not when things are at their worst for the oppressed but when they are getting better. It would be a long time after 1848 that things began to get better for the Irish people.

Daily life in Van Dieman’s Land

Initially, O’Brien’s impressions of the Tasmanian countryside were coloured by homesickness. Van Diemen’s land might have its Avoca but he longed for the Vale of Avoca in County Wicklow, immortalised in song by Thomas Moore. Reading of his impressions, one has the feeling that he was in fact influenced by romantic balladeers like Moore rather than by objective observation of the magnificent semi-wilderness of the Tasmanian bush. And of course, like most of his contemporaries, he was totally blind to the spiritual significance with which the aboriginal people had invested the environment. But as a landowner himself he was keenly interested in farming conditions and local husbandry. He even considered following John Mitchel’s example, investing in a farm and bringing out his family (he had seven children) but ultimately decided against this course. ‘Nothing has yet shaken my determination to abstain in whatever sacrifice to myself from placing my wife and children under the control of the brutes who govern the prisoner population of this colony’, he wrote.

Although O’Brien suffered because of the separation from his family and friends in Ireland he did not lack for company or social life. His journal and letters record the routine existence of a country gentleman. He studied classical authors, wrote of his impressions, rode and walked about the countryside, and went to St Matthew’s Anglican church, where he struck up a friendship with the Revd. Seaman. For a short time he moved to the Avoca region to become tutor to the young sons of Dr. Brock, an Irish naval surgeon.

Although initially he felt cold-shouldered by the local gentry, by November 1852 he was able to write to his wife of ‘visits to the settlers in whose houses I feel that I am not only welcome but a cherished guest!’ The Fenton family residence, in particular, became a second home for O’Brien. Captain Fenton, Irish and Protestant, like O’Brien himself, had served in the Indian army. His wife Elizabeth and their daughters found much in common with their guest in a shared taste for literature and music. The Young Ireland movement had stimulated a prolific crop of patriotic verses and song to which Smith O’Brien no doubt introduced his hostess and her daughters. In September, 1852 he asked Lucy to send ‘a copy of Bunting’s Irish melodies and the quarto edition of the Songs of the Nation which I have promised to Mrs. Fenton’.

Captain Fenton had a more substantial reason for cultivating the company of his fellow-Irishman. He was a member of the Tasmanian Legislative Council and a leading advocate of Tasmanian self-government. O’Brien had represented his native Limerick in the House of Commons in London for seventeen years so had invaluable expertise to impart. In later years Fenton became Speaker of the Tasmanian legislature and was a member of the committee to draft a constitution for Tasmania. O’Brien for his part drafted a model constitution and worked on his ‘Reflections in Exile’, published after his release as Principles of Government.

Pardon

Well-wishers, not only in Ireland but also in England and America, campaigned ceaselessly for a pardon for O’Brien. In his time he was a celebrated figure in many countries. A conditional pardon finally came through in the summer of 1854. Writing to his wife, O’Brien rejoiced not only in the pardon, but that he was not asked to retract or apologise for his actions. ‘I had firmly resolved’, he wrote, ‘not to say or write or do anything which could be interpreted as a confession on my part that I consider myself a “criminal” in regard to the transactions of 1848.’

The gold cup presented to William Smith O’Brien at Melbourne in 1854. (National Museum of Ireland)

Before Smith O’Brien departed from Tasmania after his five-year sojourn, he was feted at a series of functions and presented with congratulatory addresses at Hobart and Launceston. In Melbourne ‘Long John’ O’Shanessy, later Sir John and premier of Victoria, organised a testimonial dinner for O’Brien and his comrades. Various local communities also honoured him, including the inhabitants of the Bendigo goldfields.

His final pardon came through in 1856, expedited because so many of those serving with distinction in the Crimean campaign were Irish. He was then free to return to Ireland, having spent the intervening years in Brussels. Home at last, he was again honoured and feted. And in America he received a hero’s welcome and met President James Buchanan.

His final years were less happy. His health failed and in 1861 his beloved wife died. He himself died at the age of sixty in 1864. He is buried in Rathronan churchyard in County Limerick.

Monument

Six years later the statue which stands in O’Connell Street, Dublin, just north of the O’Connell monument, was unveiled. John Martin, MP for Meath, another veteran Young Irelander and former Tasmanian exile, performed the ceremony. Neither Edward, the Smith O’Brien son and heir, nor Lord Inchiquin, head of the family, was present. It had been a constant preoccupation with Smith O’Brien in exile that his children should be educated to take pride in their Irish heritage and to serve their country. But, he had written to Lucy, ‘I have never endeavoured to force patriotic feeling upon the minds of our children’. Presumably Edward availed of his prerogative to disagree with his father’s politics. But the father’s spirit of service was nobly carried on by his daughter, Charlotte Grace (See HI 4.4), who devoted her life to improving conditions of travel and settlement for thousands of young Irish women emigrants to the United States at a time when social services were minimal or non-existent.

Carmel Heaney is a retired civil servant.

Further reading:

R. Davis, The Young Ireland Movement (Dublin 1987).

B. Touhill, William Smith O’Brien and his Irish Revolutionary Companions in Penal Exile (Missouri 1981).

D. Gwynn, Young Ireland and 1848 (Cork 1949)

T.F. Sullivan, The Young Irelanders (Tralee 1944).