‘Will the show go on?’

Published in Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2017), Volume 25The IRA’s Civil War campaign against Dublin’s cinemas and theatres

By Gavin Foster

Above: Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins—promised military protection and compensation for any damages if cinemas reopened and armed plainclothes guards for the Siki/McTigue fight.

The events of that evening were part of a broader anti-treaty campaign to enforce a moratorium on public amusements as a protest against Free State executions and mass internment of republicans. The ban encompassed myriad forms of public entertainment—sports, films, plays, dances, races and hunts—and was to be enforced across the country, at least as far as the IRA’s deteriorating military position allowed. But as the centre of Free State power, with a vibrant social scene drawing thousands of patrons to the movies every week, Dublin and its cinema trade became the boycott’s focus. The short-lived campaign ultimately did little to forestall the anti-treaty movement’s defeat and the rapid consolidation of post-revolutionary normality under the Free State. It did, however, succeed briefly in preoccupying the police and military while also creating tensions between the government and Dublin’s theatre and cinema owners, thereby exposing some of the contradictions in and limits to the new state’s ‘business as usual’ policy during the Civil War.

Revolution and social life

Politics and violence impinged on and interacted with the country’s social life throughout Ireland’s revolutionary period. In the pre-revolutionary years, the Gaelic Athletic Association, the Gaelic League, the literary revival scene and advanced nationalist groups like Sinn Féin provided alternative recreational outlets alongside their cultural and political raisons d’être. With the coming of the Great War, the Defence of the Realm Act (DoRA) gave the British government wide powers to proscribe organisations and events, provisions that were increasingly used against cultural and social activities linked to separatist nationalism. From mid-1920 the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act extended the terms of DoRA, while the escalating War of Independence increasingly disrupted everyday life, from commerce and transportation to the holding of popular recreations like dances, sports matches and hunts. Crown forces occasionally banned or disrupted social gatherings in the face of republican defiance, while in other instances the IRA interfered with recreational events, particularly hunts and other social activities associated with the Anglo-Irish gentry. With the 1921 Truce everyday life began to return to normal, the popular appetite for sports and other amusements continuing unabated into the summer of 1922, when the burgeoning treaty split began to affect the public’s access to entertainment.

Civil war

The Provisional Government’s opening assault on the IRA-held Four Courts on 28 June 1922 was followed by heavy fighting in northside Dublin’s shopping, entertainment and business district. In the wake of the battle for Dublin, the Freeman’s Journal described the fighting’s impact on the entertainment landscape: the Metropole was turned into a Red Cross station and the La Scala Theatre became an artillery battery for Provisional Government troops, while the Corinthian, the Grand Central, the Pillar and other picture houses were ‘situated right in the midst of military operations’. In a surreal twist, when the picture houses reopened by mid-July, patrons were entertained to newsreels of the fighting that had just raged on the streets outside. But while the cinema trade was not too adversely affected by the outbreak of war, ‘business as usual’ proved elusive. Taking advantage of the temporary closures caused by fighting, members of the cinema employers’ association refused to reopen until employees consented to a 25% wage cut first proposed in June. The ministry of labour succeeded in having the wage issue deferred until April 1923, but the wage dispute ultimately dragged on longer than the Civil War itself.

Above: Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins—promised military protection and compensation for any damages if cinemas reopened and armed plainclothes guards for the Siki/McTigue fight.

In the ensuing months, the heavy-handed methods employed by the National Army against stubborn pockets of IRA resistance, and the public’s apparent acquiescence to Free State policies, contributed to the hardening of republican attitudes towards civilians that underlay the IRA’s policy. Republicans were particularly aggrieved by the executions of captured Volunteers, a development that few public bodies vigorously denounced once the precedent was established. In early March 1923, the news that groups of republican prisoners were taken out and blown up with mines at Ballyseedy, Killarney and Cahirciveen, Co. Kerry, provided the immediate catalyst for republicans’ offensive against Irish social life.

The IRA’s campaign against public amusements

The campaign against public amusements was announced on 14 March in a proclamation issued by Patrick (P.J.) Ruttledge, minister for home affairs in the underground ‘Government of the Irish Republic’. Condemning Free State executions and mistreatment of internees, the proclamation obliquely referenced the ‘tragedies of Kerry’ when it accused the pro-treaty army of ‘daily violations of the usages of war’. To bring attention to these ‘crimes’ and out of respect for the feelings of republican prisoners and their ‘bereaved families’, it concluded by ordering an indefinite period of ‘national mourning’ to be observed by the suspension of all sports and amusements.

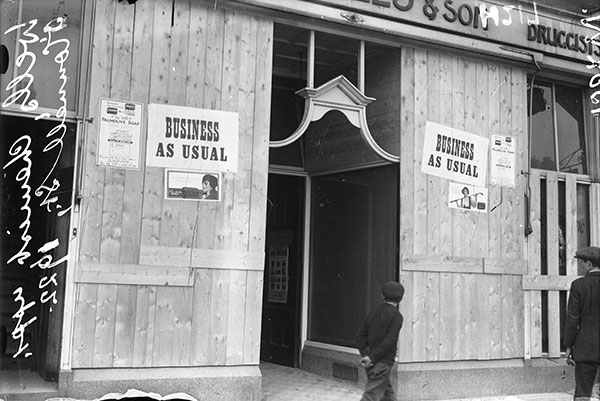

Above: ‘Business as usual’—a Dublin shop boarded up as a result of damage during the Civil War. It also sums up the policy of the Irish Free State. (NLI)

Several of the recreations singled out—horse-racing, hunting and coursing—have deep roots in Irish rural life, but a specific reference to picture houses reflects the increasingly urbanised, electrified and consumerist nature of Irish society by the early twentieth century. In 1923 there were over 100 cinemas and theatres with projectors in the 26 counties (57 more could be found across the border). Dublin alone was home to about three dozen of these. Typical cinema fare consisted of Pathé Gazette newsreels (pre-screened by a Free State Army censor), Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton comedies, Sherlock Holmes productions and popular melodramas. As this was the era of the silent film, showings were accompanied by live piano, organ or even full orchestra. Beyond cinematic fare, Dubliners had a wide menu of performing arts to choose from, including pantomime, juggling, comedy, ventriloquists, dance and dramatic performances.

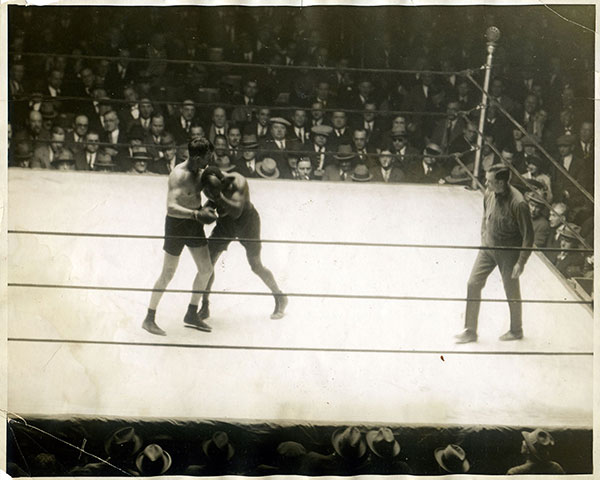

‘Battling Siki’ vs McTigue

The day after the boycott was publicised, a majority of the city’s cinemas and theatres failed to open. Instead, representatives of the theatre trade met with Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins, who promised military protection and compensation for any damages if cinemas reopened. With the light heavyweight world championship between Senegalese boxer ‘Battling Siki’ (a.k.a. Ahmadou ‘Louis’ Mbarick Fall) and Clare-born American fighter Mike McTigue scheduled for St Patrick’s Day at La Scala Theatre, O’Higgins also promised armed plainclothes guards for that event. A meeting of the Free State executive resulted in three further decisions: (1) the minister for defence would order the entertainment industry to continue ‘business as usual’ (including advertising), with fines for non-compliance; (2) republican prisoners would be punished with a suspension of ‘privileges’; and (3) the press would not be permitted to report on the IRA’s ban.

Sufficiently reassured, cinema/theatre proprietors agreed to resume business the following day, Friday 16th. Nonetheless, the military circulated its order against future business closures, pointing out that acquiescence to such threats only served to encourage the IRA’s ‘conspiracy to obstruct the working of the government’ and henceforth would be a punishable offence. Meanwhile, having received an IRA message threatening ‘serious consequences’ if Saturday’s prizefight went ahead, La Scala’s owners and both boxers were given police protection.

It is often assumed that the historic fight went ahead without incident, but in fact the IRA did attempt to disrupt it, albeit with negligible results. That night a powerful mine exploded behind the Pillar Picture House, throwing orchestra members from their seats and causing a stampede in Sackville Street. While the Pillar was assumed to have been the target, the Freeman’s Journal surmised that the mine was intended to damage underground cables supplying power to La Scala and/or to down wires relaying the fight across the Channel. The bombing caused only minor damage, however, and the Pillar resumed its programme, while McTigue defeated ‘Siki’ after twenty rounds (see HI 16.2, March/April 2008, TV Eye, pp 50–1).

Its moratorium on amusements so swiftly countered, the IRA escalated its threats against businesses. On the 19th, two men approached the Assembly Hall Picture House demanding to know why it had opened on St Patrick’s Day. Although the owner was shaken, the DMP convinced her to stay open. Such was not the case at the Bohemian and Blacquiere that night, and both remained closed the following night despite promising the authorities otherwise. The 21st and 22nd saw similarly mixed reactions: upon being served with a ‘final warning’ from the Dublin Brigade, two Camden Street proprietors stayed open with protection, but half a dozen other cinemas (including one on Talbot Street that was showing the Siki–McTigue fight) either did not open or closed hastily after receiving threats. Several of these ignored police orders to resume operations.

The man in the blue serge suit

Over the next week the IRA began backing up its threats with actual violence. On 23 March the Carlton Picture House on Sackville Street had a hole blown in its entrance. Alerted to flames crawling along the fuse moments before the explosion, a military patrol rushed to the scene and exchanged gunfire with two fleeing ‘Irregulars’. One of the perpetrators, described enigmatically as ‘a man in a blue serge suit’, escaped by shielding himself with a passerby, but his accomplice, identified as Volunteer Patrick O’Brien (26) of Clontarf, fell in a hail of bullets outside of the Masterpiece Picture House on Talbot Street. The only apparent fatality in the IRA’s campaign against Dublin’s picture houses, he reportedly uttered the cinematic dying words, ‘I think I’m done for … Get me a priest.’ On the 29th the Fountain Picture House was targeted with a similar attack, only this time in broad daylight. According to witnesses, two women arrived at the James Street Chapel around 7.30am and handed an attaché case to two waiting men. One of the latter was seen returning from the direction of the Fountain shortly before a petrol bomb exploded out front, causing minor damage. Other Dublin picture houses that were damaged in the IRA’s anti-amusements campaign included the Grand Central Cinema, the Pillar and the Stella.

‘Business as usual’?

Above: Advertisement for the Stella Cinema in Rathmines, Dublin. (Freeman’s Journal, 21 April 1923)

O’Higgins eventually relented on compensation claims. His initial response suggests, however, that anti-treatyites weren’t the only impediment to the normalisation of conditions desired by many civilians. This is reinforced by the republican movement’s attempt to revive its campaign against amusements in the summer/autumn of 1923 as a protest against continued internment months after the IRA dumped arms. This time the roles were reversed: with their agitation against renewed public safety measures, republicans were acting as the advocates of post-revolutionary normalisation, while the government’s insistence on maintaining a war footing meant that ‘business as usual’ would elude the Free State for some time after the Civil War ended.

Gavin Foster is Associate Professor in Irish Studies at Concordia University, Montreal.

FURTHER READING

‘Attempt by Anti-Government Forces to Prohibit Sports and Amusements’, JUS/H84/13, National Archives of Ireland.

T. Farmar, Ordinary lives: three generations of Irish middle class experience, 1907, 1932, 1963 (Dublin, 1991).

M. Walsh, Bitter freedom: Ireland in a revolutionary world 1912–1923 (London, 2015).