Whither the National Library of Ireland?

Published in Issue 1 (January/February 2016), Platform, Volume 24MINISTER HUMPHREYS ANNOUNCES A REFURBISHMENT PROGRAMME, BUT FUNDING FOR STAFFING AND DAY-TO-DAY OPERATIONS IS STILL INADEQUATE

By Felix M. Larkin

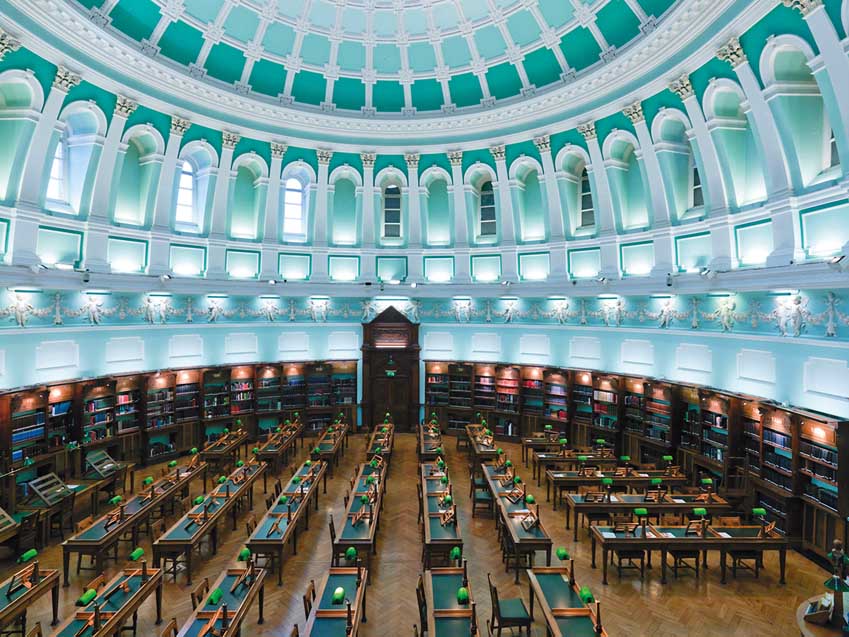

As a long-time critic of the neglect of the National Library by governments of all hues, it would be churlish of me not to welcome the recent allocation by the Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Heather Humphreys TD, of €10 million for work on the refurbishment of the Library’s iconic Kildare Street building, which dates from the 1890s. The priority will be to upgrade storage facilities for the Library’s collections and to meet other urgent needs, such as enhanced visitor and reader facilities and modern standards of health and safety. It is understood that the work will begin in late 2016 or early 2017 and that it will take about two years to complete.

Minister Humphreys’s announcement follows a damning valedictory letter sent to her in July 2015 by the outgoing board of the Library, in which they expressed their deep concern about the Library’s ‘inability to fulfil its statutory function of protecting and preserving the nation’s documentary heritage’. In particular, the board were concerned about the inappropriate nature of the library’s storage space, with specific mention of fire safety. Earlier, in June, Catherine Murphy TD had raised the question of the safekeeping and security of the Library’s collections in the Dáil. She stated on that occasion that she was ‘quite shocked at the lack of protection against fire and flood in the National Library’ and asked whether we had not learned from the 1922 fire in the Public Record Office in the Four Courts complex that ‘wiped out 700 years of history’.

Commenting on the outgoing board’s letter, the Irish Times in an editorial on 9 November reminded us that ‘there is an onus on each generation to preserve and protect the national cultural treasures in its care, to keep them secure for future generations’. This was not the first time that the Irish Times had been moved to comment on the Library’s difficulties. Some 46 years ago it published an editorial entitled ‘Unfair to books!’, in which it stated that ‘the condition of the National Library is one of the major scandals of our country’, and it highlighted that the Library was ‘deficient in space, staff and supplies’ and that ‘it does not buy all it should buy, partly because it has nowhere to put new acquisitions now, partly because it lacks funds’. It is depressing to note how little progress has been made in the intervening years.

Why has there been such neglect, not only of the National Library but also of other national cultural institutions such as the National Museum? There was—and maybe still is—a certain antipathy towards them in the government sector, and especially in the Department of Finance, and it is more than just the default Department of Finance position of turning down all demands for money.

I fear that the reason is, to some extent, a pervasive anti-intellectualism on the part of successive governments and their civil servants. As Tom Garvin explained in Preventing the future, the dangers of human knowledge—rather than its possibilities—governed both education and cultural policy in Ireland for a long time. Religion and patriotism were the twin pillars of that policy—as evidenced in 1950 when the then Minister for Education, Richard Mulcahy, declared that ‘the foundation and crown of youth’s entire training is religion’ and stressed ‘the importance of seeing today our education work in the perspective of the nation and its history’. He expanded on the latter point as follows:

‘We want all our young people to love their country and loving her to serve her loyally and faithfully in whatever walk of life their lot may be cast . . . Education in this country has a task laid upon it in this connection that is almost unique. There is a breach which it has to fill, and any attempt to ignore that fact or belittle its importance would eventually, I think, be disastrous to the nation’s strength and character.’

The education and cultural sector was thus required to make good a perceived lack of patriotism, and the advancement of learning took second place to that. The remnants of such attitudes persist today.

Furthermore, there seems to me to have been a particular antagonism in government circles towards the Library and the Museum because they are Dublin-based—institutions of the Pale—rather than of the so-called ‘real’ Ireland. The fact that they are older than the state—ancien régime institutions, the products of ‘enlightened’ British efforts to kill Home Rule with kindness—is undoubtedly also a factor. They were not part of the Gaelic Revival and they never bought into the ‘Irish Ireland’ mythology, despite the presence of some fine Gaelic scholars on the staff over the years. Moreover, there was a tradition of strong directors of both institutions who knew their own minds and refused to take directions from mere bureaucrats or blinkered politicians.

Lest we rejoice too much that all that has changed following Minister Humphrey’s welcome announcement, let me emphasise that the money now being made available is strictly for capital work. It will not provide for the huge shortfall in funding for the operational needs of the Library. In their valedictory letter to the minister already referred to, the outgoing board stated unequivocally that the Library does not have adequate specialist staff and resources to enable it to collect and preserve Ireland’s documentary heritage. They told Minister Humphreys that a year-on-year budgetary increase in the order of at least €500,000, including an increase in the pay allocation, over the next two to three years is necessary to offer the kind of service that should be available.

In this regard, it should be noted that the Library’s latest Annual Review records that its funding, both current and capital, was €6.34 million in 2014, which represents a whopping 47% decrease in funding since 2008. There is a staff of 86, as compared to 113 in 2008. The staffing in the analogous National Library of Scotland and National Library of Wales is 280 and 277 respectively. In fairness, Minister Humphreys did secure extra funding of €600,000 for 2015 and again for 2016, but this is clearly inadequate for the Library’s needs. The €500,000 which the outgoing board have said is necessary would be additional to that.

The government’s niggardly treatment of the National Library stands in stark contrast to their lavish funding of the Easter Rising centen-ary commemorations. The Library is the key body for meaningful research in Irish history and culture, and the allocation of that level of funding for the 1916 commemoration while denying the Library adequate funds to enable it to carry out its essential functions means that the government is favouring commemoration over history. The Romans used to think that providing panem et circenses for their citizens would keep them happy. This government apparently takes the same dismal view. Its policy seems to be that it is better to have a spectacle in 2016—a patriotic circus—than a deeper understanding of our history. Government priorities have not changed much since Richard Mulcahy’s days as Minister for Education.

Felix M. Larkin is a former member of the statutory Readers’ Advisory Committee of the National Library of Ireland.