When Saxon strangers first came to Ireland: the raid on Brega, AD 684

Published in Features, General, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2011), Pre-Norman History, Volume 19 In AD 684 an episode unique in Irish history occurred: a major military expedition by Anglo-Saxon forces. As with all historical events of this period, the details are sparse. The raid was on the Irish kingdom of Brega (roughly present-day County Meath) and was a naval attack probably launched via the Isle of Man, then in Saxon hands. Contemporary Irish annals give few details, although the Annals of the Four Masters, compiled almost a thousand years later, state that there was a general devastation of the region and its churches, and that goods and hostages were carried off by the Saxons in their ships.The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for that year laments that churches were attacked and burned, and names the Saxon commander in the field as the ealdorman Berht. Bede in his Ecclesiastical history of the English people calls it an unwarranted attack on an innocent and Christian people, and criticises Ecgfrith, king of Northumbria, who planned and authorised the raid. Bede relates how clerics, including Ecgbert, a Saxon bishop working in Ireland, warned against such a course of action and that God would punish the Saxon king for such a deed. Another contemporary reference is given by the Irish annals, which show that in 686 Adomnán, the abbot of Iona, travelled to Northumbria to negotiate the release of 60 hostages seized from Brega and returned to Ireland with them. Nowhere in these sources is a motive or reason given for the attack, but perhaps we can gain clues from an analysis of the history of the period leading up to the event.In the seventh century the islands of Ireland and Britain were both composed of a shifting mosaic of kingdoms, where a powerful individual king or dynasty could emerge to claim dominance over his fellow kings. In Ireland the Uí Néills had emerged as the dominant dynasty, while in Anglo-Saxon England the most powerful kingdom was Northumbria, although in the latter half of the seventh century it was in decline, threatened from the south by the growing strength of the Saxon kingdom of Mercia.

In AD 684 an episode unique in Irish history occurred: a major military expedition by Anglo-Saxon forces. As with all historical events of this period, the details are sparse. The raid was on the Irish kingdom of Brega (roughly present-day County Meath) and was a naval attack probably launched via the Isle of Man, then in Saxon hands. Contemporary Irish annals give few details, although the Annals of the Four Masters, compiled almost a thousand years later, state that there was a general devastation of the region and its churches, and that goods and hostages were carried off by the Saxons in their ships.The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for that year laments that churches were attacked and burned, and names the Saxon commander in the field as the ealdorman Berht. Bede in his Ecclesiastical history of the English people calls it an unwarranted attack on an innocent and Christian people, and criticises Ecgfrith, king of Northumbria, who planned and authorised the raid. Bede relates how clerics, including Ecgbert, a Saxon bishop working in Ireland, warned against such a course of action and that God would punish the Saxon king for such a deed. Another contemporary reference is given by the Irish annals, which show that in 686 Adomnán, the abbot of Iona, travelled to Northumbria to negotiate the release of 60 hostages seized from Brega and returned to Ireland with them. Nowhere in these sources is a motive or reason given for the attack, but perhaps we can gain clues from an analysis of the history of the period leading up to the event.In the seventh century the islands of Ireland and Britain were both composed of a shifting mosaic of kingdoms, where a powerful individual king or dynasty could emerge to claim dominance over his fellow kings. In Ireland the Uí Néills had emerged as the dominant dynasty, while in Anglo-Saxon England the most powerful kingdom was Northumbria, although in the latter half of the seventh century it was in decline, threatened from the south by the growing strength of the Saxon kingdom of Mercia.

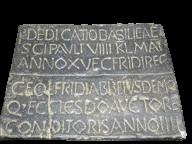

An inscribed stone dedicated to Ecgfrith, king of Northumbria, in St Paul’s Church, Jarrow, dated April 685, the month before the battle of Nechtansmere, his ill-fated venture against the Picts.

Aldfrith and the Northumbrian succession

To their north, the Northumbrians claimed lordship over the kingdoms of the Irish in Dál Riata, the British of Strathclyde and the Picts, who were often in open revolt. When Ecgfrith launched his attack on Ireland he had been king for fifteen years, but he had other problems besides external pressures on his kingdom: in a violent world, where kings often met their death on the battlefield, he had no heir. Two of his brothers had been killed in battles with Mercia, and he had no sons of his own. He had married Aethelthryth, the daughter of the king of East Anglia, but she had declared at their marriage that she was devoting herself to God and intended to lead a chaste and celibate life. Bede praises this decision; while Ecgfrith’s immediate reaction is not recorded, he spent the followingdecade bribing his bishops with grants of land to persuade her to change her mind. She refused to do so and after twelve years Ecgfrith eventually remarried. The only effective heir to Northumbria in the 680s was Ecgfrith’s elder half-brother Aldfrith, an Irish-speaking scholar and poet who lived in a monastery on Iona.

This Pictish carved stone at Aberlemno Church, five miles from the battle site, is a near-contemporary depiction. Ecgfrith is shown in the lower right-hand corner, being attacked by ravens. (Barbara Ballard and Martin McCarthy)

Aldfrith’s father was Oswiu, a Saxon prince who lived in exile in Dál Riata with a number of his brothers and followers during the 620s and 630s; one of his brothers, Oisric, is recorded in the Annals of Tigernach as falling in battle in Ireland in 632 while fighting alongside the king of Dál Riata. While in exile, Bede tells us, these pagan Saxon princes received Christianity from their Irish hosts. Oswiu, who would later become king of Northumbria, fathered a child with an Irish princess, Fín, the daughter of Colmán Rímid of the northern Uí Néill, who is listed as a high king of Ireland. Their son Aldfrith, with Irish and Saxon royal blood in his veins, is remembered in the Irish sources as a poet and was not a warrior like his forefathers; he is never recorded as having fought in battle.In Ireland, where he was known as Flann Fína, he was recognised for his writing and learning, and Adomnán, the abbot of Iona and heir to the tradition of St Columba, regarded him as a friend of great learning and a man held in high esteem by the Irish church. His image in Saxon England was somewhat different. Bede felt that he was illegitimate at best and cast doubt on his being a son of Oswiu, while a sister of Ecgfrith confided in the Saxon bishop Cuthbert that she doubted the very existence of the shadowy figure of her Irish half-brother.Despite lacking an heir, in 684 Ecgfrith was planning a campaign against the rebellious Picts, but he first launched an attack against the southern Uí Néill kingdom of Brega, which was ruled at the time by the high king Fínsnechta Fledach. What was the motivation for such a venture, since Bede claimed that the Irish were no threat to Ecgfrith? Was Aldfrith preparing to move against Ecgfrith with the support of his Uí Néill relatives and did Ecgfrith wish to seize hostages to prevent this (to ‘get his retaliation in first’)? Everything we know about the character of Aldfrith casts doubt on this, but Ecgfrith did know the value of holding hostages; as a child, he had himself been held hostage by the Mercian king Penda, and was only released when his father killed Penda in battle. If Ecgfrith now wanted Irish hostages, surely it was to prevent Irish kings from supporting the Picts, whether that support came from Ireland itself or from the Irish kingdom of Dál Riata.

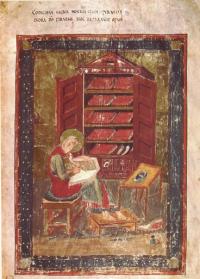

Aldfrith—an illustration added to the Codex Amiatinus, produced in Northumbria during the reign of Aldfrith. The image is of the Old Testament prophet Ezra, but it is also seen as a representation of Aldfrith studying in his library. (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence)

How did Aldfrith become king of Northumbria?

In the spring of 685 Ecgfrith made his move against the Picts and personally led an army deep into their territory. It ended in disaster. On 20 May, at the battle of Nechtansmere, the Saxon army was obliterated and Ecgfrith and the cream of the Anglo-Saxon nobility perished on the battlefield. Bede claims that Ecgfrith’s fate was divine retribution for his unwarranted attack on the Irish and their churches, and that he had ignored clerical warnings from both Ireland and England not to attack the Picts. The sequence of events that followed the battle is unclear but somehow Aldfrith became king of Northumbria, and in 686 his friend Adomnán visited him and arranged for the hostages from Brega to be freed. Some months appear to have elapsed between Ecgfrith’s death and the accession of the new king, so how did the Irish-speaking scholar with no known military experience come to assume the crown when he was not held in high regard in Northumbria?Some twelfth-century English chroniclers wrote of a tradition that after Nechtansmere Ecgfrith was buried on the island of Iona, a place of burial for saints and kings. Irish, Pictish and Scottish kings were interred there over the centuries, and in our own time John Smith, the Scottish leader of the British Labour Party, was laid to rest there in 1994. But there is no obvious or logical reason why a Saxon king who had devastated churches in Ireland before attacking the Picts should be buried in such holy ground, and the idea has been largely dismissed. Perhaps it is not so fanciful, however.Towards the end of the eighth century the monks of the monastery of Tallaght compiled a martyrology of the saints of Ireland, drawing their names from various sources, one of which was apparently a list of the holy men buried on Iona. As well as the expected names of Columba, Adomnán and other abbots, the name of the aforementioned Saxon bishop Ecgbert appears, and his death while living at Iona is independently recorded. There is, however, an intriguing entry for 27 May: Echbritan mac Óssu [Ecgfrith son of Oswiu], someone whom the monks at Tallaght, over a century after his death, must have presumed to have been a saint because of the location of his grave. What is more startling is that when Micheál Ó Cléirigh compiled a list of the saints of Ireland in the 1620s and used the Martyrology of Tallaght as a source for his Donegal Martyrology, he directly transcribed Ecgfrith’s feast-day as 27 May, yet we know that Ó Cléirigh, the driving force behind the Four Masters, was familiar with Bede and might have been expected to know exactly who Ecgfrith was.

Iona, traditional burial place of Irish and Pictish saints and kings. How and why might Ecgfrith, the Saxon king of Northumbria, have been buried there amongst his sworn enemies? (Neilston Webcam Photo Gallery)

Who might have buried Ecgfrith on Iona?

If we accept that Ecgfrith was buried on Iona, how did his remains get there, who transported his body and why? His followers who survived the battle could have done so, knowing that his heir, Aldfrith, was living there, but this is unlikely. Bede relates that Ecgfrith’s forces at Nechtansmere were annihilated, with many survivors being taken into slavery and only a few making their way south to safety. They would not first have headed west through difficult and hostile territory to the remote island of Iona. Would the Picts have been responsible for carrying the corpse of their bitter enemy to a site where Pictish kings were buried in order to grant their hated overlord a Christian and respectful burial? Again, this is unlikely.This leaves the possibility that it was Irish soldiers who had fought at Nechtansmere who transported the body of a dead Saxon king across the mountainous spine of Scotland and presented it to their kinsman, Aldfrith. He then gave his half-brother an honourable funeral before travelling south to Northumbria to claim his inheritance. There is no record of who travelled with him or whether a Saxon delegation came to meet him, only that it was some months before he became the new king of Northumbria. The only definite fact is that Adomnán, the leading Irish churchman of the time, was in the Northumbrian capital the following year, arranging for the Irish hostages to be freed. The contemporary Irish sources, including Adomnán’s Life of Columba, say little about these events, in an almost aloof manner, while English sources are equally silent, almost as if the whole affair was something of an embarrassment. Even Bede is unusually reluctant to flesh out the details, which he must have known as he lived through these events. He is content to comment that Northumbria’s borders and sphere of influence were now reduced and that Aldfrith’s reign would prove to be a peaceful one.The apparent conclusion is that Ecgfrith had been correct in his intention of attacking Ireland to prevent Irish support for the Picts but that the manner of the attack backfired on him in a spectacular way. In moving against the southern Uí Néill in Brega and seizing hostages from them, he picked the wrong target; prospective Irish support for Aldfrith would have come from his close kinsmen, the northern Uí Néill. Dál Riata, anxious to throw off the yoke of Northumbrian overlordship, would have had every motivation to assist in such a venture.It is an intriguing thought that the blood of an Irish high king might have flowed, via Aldfrith, through the veins of the English royal line, but this was not to be. Two of Aldfrith’s sons succeeded him, but his line became extinct. In fact, the lineage of Irish kingship in the British monarchy came from the Stuarts, with James VI of Scotland, later James I of England, acknowledging Fergus Mór mac Eric, a king of Dál Riata at the beginning of the sixth century, as his direct ancestor. It was as a direct result of Nechtansmere that Anglo-Saxon acquisition of Scottish lands failed and that a kingdom of Scotland could later emerge from the integration of Dál Riata and the Pictish people. HI

Anthony Cronin is a postgraduate history student at University College Dublin.

Further reading:

F.J. Byrne, Irish kings and high kings (Dublin, 2001).T.M. Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland (Cambridge, 2000).J. McClure & R. Collins (eds), Bede—The Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Oxford, 1994).