What the witchcraft bishop did in Ireland: the controversial career of Francis Hutchinson, 1660–1739

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, 18th–19th - Century History, Early Modern History (1500–1700), Early Modern History Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2010), Volume 18

A man and his daughter by Flemish painter Jan Vierpyl. It is no longer thought to depict Irish-born moral philosopher Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), since at the time of its painting (1721) he was only 23, unmarried and could not possibly have had a teenage daughter. On the other hand, in 1721 Bishop Francis Hutchinson was 61, had a daughter in her early teens and was a committed book-collector (note the bookshelves in the background). Moreover, his considerable bishop’s salary meant that he had the money to commission such a portrait. (National Gallery of Ireland)

Francis Hutchinson was no ordinary clergyman. Posterity chiefly remembers him for his condemnation of witchcraft trials in his famous book An historical essay concerning witchcraft . . . (1718). He was one of the first members of the Dublin Society for the Improvement of Husbandry and Other Useful Arts, however, and wrote extensively on social and economic issues. He also developed and used a phonetic form of the Irish language to convert the Catholic, Gaelic-speaking population of Ireland to the Protestant faith. It is this conversion campaign that makes Hutchinson the perfect window through which to peer into a period of intense religious and political conflict and change—the early eighteenth century.

Hutchinson and witchcraft

Although there was legal provision for the prosecution of witches in early modern Ireland, and belief in witchcraft extended across denominational boundaries, witchcraft trials and executions were extremely rare. In contrast, when the last person in England was executed for witchcraft in Exeter in 1685, around 500 people, mainly women, had been executed during the preceding century. And this figure represents just over one per cent of the estimated 40,000 witches put to death in western Europe between 1400 and 1800.

Hutchinson began writing his book on witchcraft in the early eighteenth century while curate in a small country parish in Suffolk. Although by this time successful witchcraft prosecutions had slowed to a trickle in Scotland and had come to a halt in England, accusations continued to be made by members of the lower orders. Occasionally these led to trials, such as that of Jane Wenham in nearby Hertfordshire in 1712. After a particularly bitter and socially disturbing trial, Wenham was acquitted. All this occurred against a backdrop of decades of war between Britain and its allies and Louis XIV’s France.

Hutchinson was at Wenham’s trial and spoke to her afterwards on the estate of a wealthy local Whig magnate, Colonel Plummer. She had been placed there for her own safety, away from the angry mobs still convinced of her guilt. Largely unconcerned with the human cost involved, Hutchinson became convinced that witchcraft trials posed a serious threat to public order and thus to social and political stability, especially in times of crisis such as war. In Ireland, on the other hand, Hutchinson came to the conclusion, after much careful study, that unlike in England the threat to the status quo was negligible: belief in witchcraft existed but no trials arose from them.

The Irish language and conversion

![On arrival in his new diocese of Down and Connor in the early 1720s, Hutchinson noted down in his commonplace book instances of witchcraft and popular magic reported to him by locals: (fourth line) ‘One swore that [on] taking aim at a hare an old wo[ma]n rose up’. (PRONI)](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/76_small_1265286851.jpg)

On arrival in his new diocese of Down and Connor in the early 1720s, Hutchinson noted down in his commonplace book instances of witchcraft and popular magic reported to him by locals: (fourth line) ‘One swore that [on] taking aim at a hare an old wo[ma]n rose up’. (PRONI)

His faith in the converting power of Irish was out of tune with many of his contemporaries. Unlike them, he was convinced that Irish, not English, was the everyday language of Catholic Ireland. He also believed that by presenting the ‘true word of God’ in the vernacular he was releasing the benighted Irish from the bonds of religious ignorance and oppression. In short, he was carrying on the work of the first Protestant reformers of the Reformation. By the ‘true word of God’ Hutchinson meant the Protestant religious message as interpreted by the Church of England and Ireland.

The 1721 manuscript version of the Rathlin alphabet, included in modified form in the Church catechism in Irish. (PRONI)

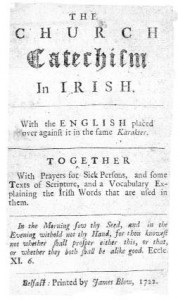

Hutchinson believed that he had found the answer to why conversion schemes using Protestant materials written in Irish had failed during the previous two centuries: the majority of Irish Catholics could read neither English nor Irish. Hutchinson thus reasoned that if he could enable Irish-speaking Catholic Charity School children to read Protestant religious material in Irish, he could convert them in large numbers. This could be achieved both quickly and easily by means of a new method of presenting the Irish language, first showcased in his Church catechism in Irish of 1722. Hutchinson’s catechism used a more phonetic writing system that bore a closer resemblance to English than traditional literary Irish. In Hutchinson’s opinion, English was the more linguistically perfect language, a modern improvement upon ancient languages such as Irish.

Hutchinson argued that many of the letters in written Irish words were not pronounced when spoken and thus should be deleted. He went on to suggest that the traditional Irish alphabet proved difficult to learn because it had ‘neither h in its proper sound, nor k, nor i consonant, nor v, nor w, nor x, y, z’. He consequently increased the number of letters in the Irish alphabet from 18 to 26, making it identical to its English counterpart. He also ensured that the translation used the dialect of the region in which it was intended to be used. He provided the reader with a short grammatical introduction, a vocabulary, and some useful snatches of conversation presented in the form of a series of questions and answers: ‘K[est]. In lavirin tu Bearl?’ (‘Question. Can you speak English?’). Finally, he printed the Irish translation in a Roman typeface instead of using the traditional Gaelic one. The Roman typeface was not only far cheaper to produce but would also, he hoped, familiarise those who learned to read Irish using it with written English. In common with many Irish Protestants, he hoped that English would eventually supplant Irish as the common tongue.

Aware that there was little regard within the country at large, especially among Charity School enthusiasts, for proselytising in Irish, he believed that if he could demonstrate the effectiveness of his new Irish in his own Charity School, other schools would soon start to use it. Hutchinson chose Rathlin Island as the site for a pilot scheme because it was one of the few places in his diocese where a large concentration of Irish-speaking Irish Catholics lived. In the early eighteenth century the counties of Antrim and Down, in which the diocese of Down and Connor lay, possessed the smallest proportion of Catholics of all the counties in Ireland. There was also no Catholic priest resident on Rathlin to object to his plans for the island.

Title-page and pages 8 and 9 of the pamphlet at the core of Hutchinson’s ‘Rathlin scheme’, The church catechism in Irish, with the English placed over against it in the same karakter . . . (James Blow, Belfast, 1722).

In 1722, despite the timely intervention of a priest from the mainland, Father Dominick O’Brallaghan, Hutchinson was able to confirm 40 Catholic schoolchildren from Rathlin in the Anglican faith. It is uncertain, however, whether it was the promise of new clothes or the effectiveness of the catechism that effected the children’s ‘conversion’. It is also unclear how permanent their switch of faith was. In any case, Rathlin was the only place the Church catechism was ever used and was the only one of his planned phonetic devotional aids to be published. It was the linguistic innovation of the Catechism that plunged the Rathlin project into controversy and ultimately failure: conversion schemes were something few clergymen could publicly deny to be worthwhile, but altering the way languages were written was quite a different matter. This was at every turn mocked and condemned by members of polite society, his clergy and the episcopate.

In any case, by the early 1730s Hutchinson had become convinced that only a small proportion of the Irish Catholic population were committed to a bloody rebellion and slaughter of Protestants. The experience of living among Catholics on his estate near Portglenone between 1729 and 1731 had convinced him of this fact. His new, lower sense of political threat drained his conversion schemes of their rationale. Thus, by that time, he showed little or no interest in supporting them, far less developing or implementing them. As a result of this change of outlook, Hutchinson’s view of the Catholic problem had become similar to that held by the majority of his fellow Irish Protestants.

Hutchinson died on 23 June 1739 and was buried two days later under the chancel at the Portglenone chapel of ease that he had built at his own expense a few years earlier. The fact that he did not want to have his body sent back to Derbyshire to be buried, unlike his sister Mary, attests to the affection he had by this time for his new homeland. HI

Andrew Sneddon lectures in history at the University of Ulster.

Further reading:

M. Brown, C. I. McGrath and T. P. Power (eds), Converts and conversion in Ireland, 1650–1850 (Dublin, 2005).

P. McNally, ‘Irish and English interests: national conflict within the Church of Ireland episcopate in the reign of George I’, Irish Historical Studies 39 (1995), 295–314.

A. Sneddon, Witchcraft and Whigs: the life of Bishop Francis Hutchinson, 1660–1739(Manchester and New York, 2008).