Was the War of Independence necessary?

Published in Issue 4 (July/August 2019), Letters, Volume 27Sir,—It is good that Padraig Yeates (Letters, HI 27.3, May/June 2019) ‘would largely concur’ with my analysis and with Martin Mansergh’s observation (Platform, HI 27.2, March/April 2019). However, two points in his letter deserve further consideration.

Firstly, there is Dr Yeates’s suggestion that a campaign of civil disobedience in Ireland might have achieved the country’s self-determination by itself because ‘not alone were the Irish white and Christian but also they were citizens of the United Kingdom, a liberal middle-class urban democracy in which public opinion and the rule of law mattered’. The facts speak differently. Certainly, British liberal constitutionalism would kick in after months of guerilla struggle in 1921. In 1918–19 it was less alert. The level of IRA activity was far lower than in the next two years (in County Cork, eight attacks; in County Tipperary, four, plus Knocklong). On the other hand, the colonial regime refused to notice the vote of Irish democracy.

The republican movement held back from initiating a national military campaign, seeking to negotiate with the British, preferably at the peace conference. In contrast, the United Kingdom government banned Dáil Éireann, as well as the Volunteers, prepared a Better (!) Government of Ireland Bill, more restrictive than its Home Rule Act, and recruited Freikorps to enforce its will. It was out to smash the republic militarily. However, that republic responded.

Of course, as Padraig Yeates says, Britain had been weakened by its part in the world war, but so had everybody else, apart from the United States. Indeed, the UK had gained territory. Its rulers had reason to believe that they could crush the Irish as they had done in the past when England was, if anything, weaker.

It can be said that Britain underestimated the seriousness of republicanism, seeing it as a police problem. Similarly, as Padraig Yeates shows, it overestimated the Bolshevism of Irish Labour, seeking to keep it appeased. However, had Labour been leading Ireland’s struggle, even by civil disobedience, it would have had to turn to the gun, if only to defend itself against Britain’s anti-Bolshevik crusade. Nonetheless, its fight would have been for a better future than that projected by Sinn Féin.

This leads to a second point. Along with Tony Canavan (in the same issue), Padraig Yeates brings to your pages the case of the 1919 Belfast engineering strike. He remarks that the UK government was more afraid of it than it was of the armed struggle represented then by Soloheadbeg. He notes, too, that the strike was a bigger affair than the Limerick Soviet. The question posed by all this is: why was the great strike forgotten, even after memories of the soviet had been revived over the last 50 years? The answer lies with Belfast Labour, just as Limerick Labour publicised its city’s battle. Of course, the Belfast workers had bigger problems with which to contend, but commemorating a non-sectarian fight might have helped them deal with them.

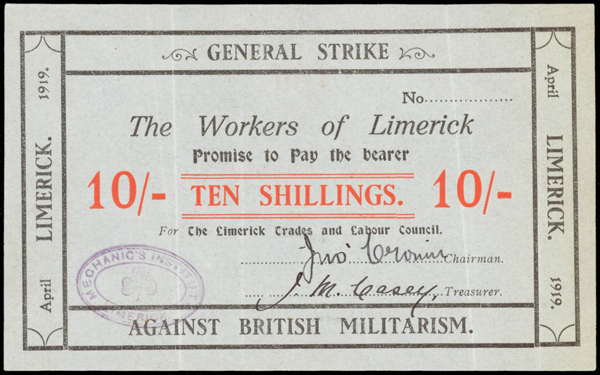

Above: A Limerick Soviet money voucher. ‘They [Limerick workers] declared proudly their soviet status, organised civil life independent of the bourgeois institutions and demanded that Irish Labour turn their struggle into a national general strike.’

D.R. O’CONNOR LYSAGHT