Von Ranke in Dublin

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2008), Volume 16

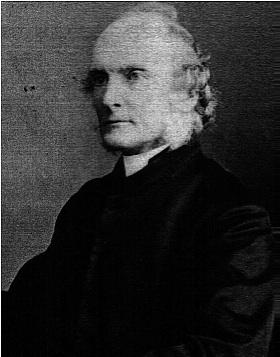

Leopold von Ranke—the father of archive-based ‘scientific’ history—in the 1860s. (Ranke Museum, Wiehe, Germany)

Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) was the most influential historian of the nineteenth century. He made important contributions to the emergence of modern history as a discipline and he has been called the father of ‘scientific’ history. Thanks to him, methodical principles of archival research and source criticism became commonplace in academic institutions, and he is generally credited with the professionalisation of the historian’s craft.

Marriage to Clarissa Helena Graves

In 1843 Ranke married Clarissa Helena Graves, born in Dublin in 1808 into a well-known Anglo-Irish family. The Graves family was highly educated, proud of its scholarly achievements and constituted an intellectual dynasty. Their roots went back to 1647, when Colonel Graves of Mickleton in Gloucestershire commanded a regiment of horse in the parliamentary army that volunteered for service in Ireland. After the Cromwellian settlement the Graves family acquired lands and public office in Limerick. Clarissa’s father, John Crosbie Graves (1776–1835), was chief police magistrate in Dublin. In 1806 he married Helena Perceval from Temple House, Co. Sligo. From 1814 the Graveses lived at 12 Fitzwilliam Square, Dublin.

After their marriage in Bowness, Windermere, England, chosen because Clarissa’s brother was vicar there, Ranke returned with his wife to Berlin. Clarissa soon became a well-known figure in Berlin society. She built up a social circle, known as the ‘Salon Ranke’, where Enlightenment thought and Romanticism were discussed, although the ideology of revolutionary movements was deliberately rejected. Even if Ranke’s house and the ‘Salon Ranke’ were dominated by conservative thought, several ‘revolutionary’ opinions of that time were discussed: the position of women, international cultural exchange and the nation-building of different states, such as Germany, Italy and the United States, as well as the role of religion in a changing society. As a well-educated poetess Clarissa was a cultural ambassador for her Anglo-Irish roots.

His History of England

Ranke had been working on an English history for a number of years. The first volume appeared in 1859 and the final one in 1868. Within this work Ranke also dealt with Ireland, and he wrote with discernible detachment. His experience in working with mainstream European history prompted him to explain why it was that nineteenth-century Ireland was characterised by a large Catholic majority ruled by a small Protestant minority, contrary to the general European experience. Unlike his contemporary

In 1843 Ranke married Clarissa Helena Graves. Born in Dublin in 1808, she came from a well-known Anglo-Irish family. (Count von der Schulenburg)

Macaulay, Ranke did not use the past to justify this situation: he used the past to understand it. Ranke, as a Continental scholar, was one of the first historians to try to explain, in an even-handed manner, a number of Irish events that were dealt with in a polemical way in England: for example, the Irish rebellion of 1641, the landing of Cromwell and his storming of Drogheda in 1649, and finally the years 1688 to 1691.

In the summer of 1865 Ranke left Berlin, with his youngest son Friduhelm, for a research trip aimed at completing this work. After spending a month in Paris, they arrived in London on 8 June. Clarissa’s youngest brother, Charles Graves, president of the Royal Irish Academy and fellow of Trinity College, Dublin, invited Ranke and his son to Dublin. It was under the auspices of Charles that Ranke had been awarded honorary membership of the Royal Irish Academy in 1849 and, after near completion of his History of England, with an honorary degree from Trinity in July 1865. Originally a month-long trip was planned. Clarissa’s brother Robert noted in a letter on 22 June that preparations went ahead for the ‘grand banquet in the Dining Hall at [Trinity] College at which of course Ranke will be one of the principal guests’. He also indicated that the lord lieutenant, Lord Wodehouse, had the intention of inviting Ranke to be a guest at the vice-regal lodge.

At the end of June 1865 Ranke went to Cheltenham to visit his wife’s brother John, professor of mathematics at University College London. It was intended that Ranke’s one-week stay would be entirely devoted to relaxation rather than work. As it happened, however, Ranke discovered another archive on his first evening there. He described to Clarissa that he walked with Friduhelm through the fields and they ‘got involved in a little war with the youth in which we (which means me as well) threw hay toward each other’. While rolling down a field, Ranke came to a halt at a path, where he met Sir Thomas Phillipps riding a horse. Phillipps invited the Rankes to visit him the following day. Phillipps possessed a great library that contained c. 20,000 manuscripts. Very much to Friduhelm’s regret, as his father’s copyist, Philipps also possessed full parliamentary records from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This proved to be Ranke’s greatest discovery, and the next day he and his son searched through the manuscripts. In fact, Ranke became so absorbed that he almost forgot his arrangements to go to Dublin.

Honorary doctorate from Trinity College, Dublin

On the morning of 4 July 1865 Ranke arrived with his son in Ireland, in time for the conferring of an honorary doctorate by Trinity on the following day. The proposal for the honorary degree came from Charles Graves, who had become a senior fellow shortly before. Ranke, however, had earlier connections with Trinity. Walter K. Kelly of

12 Fitzwilliam Square, home of the Graves family for most of the nineteenth century.

Trinity had translated two of his works: The history of the popes into English in 1843, and The Ottoman and Spanish empires into Spanish in 1857.

For Ranke, this doctorate was very important. He wrote to his wife a few days later:

‘Here in the far west I became truly a doctor of both laws. I wear the hat of the university and the robe of a doctor. I was the only one who did not have to swear the usual oath because Queen Victoria is recognised as one’s queen.’

He received a diploma to bring back home. During the banquet Ranke sat beside Lord Clancarthy, with whom he had a long discussion about the world.

After the conferment Ranke had some spare time, and Robert showed him and Friduhelm the homes of the Graveses, ‘where the one or the other of you were born and grew up, where you lived as a little house mouse with the name Clarissa’. Friduhelm enjoyed the company of his cousins, who are described as ‘a couple of talented young folks; both of them enjoy jokes; the one more in conversation, the other one even writes small satires’. Charles is described more in relation to his profession. He was a senior fellow in Trinity, although ‘he does not have to lecture himself but he is always busy there; at the same time he is the spiritual counsellor [chaplain] to the viceroy, whose trust it seems he enjoys to the highest level’. With sorrow Ranke had to inform his wife that Archbishop Trench was not present. Because of Charles’s role as chaplain, Ranke was accommodated within Dublin Castle, and he noted that ‘the apartment we stay in belongs to the government and all of the furniture is roomy and comfortable’. He stressed that his apartment was opposite the viceroy’s. It was a special arrangement, so that the viceroy could discuss history and politics with Ranke until late into the evening, and Ranke only needed to cross the hall to go to bed. Ranke was also impressed by the setting: ‘On the wide stones which divide the middle of the court, the guards march up and down in their colourful costume’.

According to Friduhelm, the stay in Dublin was a continuous celebration: every night there were parties, honours, awards and tributes. He recalled that the Irish understood how to arrange things properly. He also had the feeling that the ‘author of the popes’ was a far more famous and popular figure in Dublin than at home.

Impressions of Dublin

Ranke was in Dublin not only to receive his honorary doctorate but also to visit the sights, meet historians and important politicians, and carry out research in Dublin’s archives. In addition, he went to an American art exhibition hosted by the Royal Dublin Society. He gave his impressions of Dublin:

The Royal Irish Academy, Dawson Street, which Ranke visited in 1865. (RIA)

‘Dublin is the only capital city in the world in which the majority of the population are Catholic, but is ruled by a Protestant minority. If one goes into a Catholic Church, one can see confessionals and people in silent prayer. If one asks the nearest neighbour on the street, he will claim to hate and reject all of Catholicism. The opposition of both confessions rules feeling and opinion. In the middle, stands the statue of William III on horseback, an object venerated by one side, detested by the other. The state which he founded still exists. It still governs.’

In his letters to his wife Ranke indicated that an artist would find good studies in the people of Dublin, as he ‘recognised a lot of genuine figures and expressive faces, which were sometimes beautiful, other times ugly, but always worth watching’. He remarked with regret that nobody seemed to show any interest in ‘genuine Irish art’. Further on, Ranke mentioned three people he had met: Dr Petrie, Sir Thomas Larcom and Lord Wodehouse. George Petrie (1790–1866) was a historian and archaeologist whom Ranke described with much respect. Sir Thomas Larcom was under-secretary for Ireland (1853–68), and John Wodehouse, earl of Kimberley (1826–1902), was lord lieutenant of Ireland from 1864 to 1866.

Archives and artefacts

As a historian, Ranke’s main interests were the archives of Dublin. The first one, located in the Custom House, ‘which has documents concerning finance and property’, was described as an archive with vaulted rooms that were free of all haze and of the smell of dust. The archivist William Harding(e), who worked there for 30 years, was described as very helpful and competent, and able to find any document at any time. Harding was so excited to have a famous historian present that he showed Ranke the ‘more exceptional documents’ and repeatedly said: ‘We have this, and I have the original of that and of that as well, would you like to see it?’ The more political and genealogical records were kept in the Record Tower of Dublin Castle. Ranke noted the ‘attractively furnished’ tower and remarked that the vaults were clean and aired. This archive was run by Sir John Bernard Burke (1814–92), who was also the Ulster king of arms. It is understandable that Ranke spent a lot of time in this archive, so close to his own apartment. During his Dublin visit Ranke was confronted with several old books that he was interested in but unable to read, ‘because they were written in the Old-Irish language’. With pity Ranke concluded that the knowledge of the Irish language would disappear soon ‘because only a few study it’.

While sightseeing with Charles he was shown the large collection of Irish antiquities in the Royal Irish Academy. Of particular interest were the ogham stones, which Charles was able to translate. Indeed, Charles Graves had been one of the first Irishmen ever to translate the ogham script. After that they followed the development of millstones from the oldest rough form to the more recent ones. Ranke noted that these were without any doubt the oldest native stones but he suggested the possibility of some Roman influence. The tour included the examination of jewellery and ornaments, which made a great impression on Ranke. He noted: ‘They are heavy, pure gold, and the smaller ones delicate originality’, and they were reproduced on copies of brooches. With interest Ranke viewed the weapons, mainly made of bronze, and discussed with Charles their suitability to resist the Roman sword. Arriving at the section on Christian antiquities, Charles had to leave and a younger guide took over. While discussing with Ranke the treasures in the Academy, he stressed his fear of being killed someday while protecting the treasures. With astonishment and fascination Ranke examined the Christian antiquities, commenting that ‘there were monuments of Christian ancient times with greatest strangeness mixing symbols of superstition with religion. In fact a number of the monuments had more of an oriental and Greek influence than a Roman one’. With regret Ranke noted in his letter that Catholics shared no interest in such treasures.

General election

Charles Graves (1812–99), fellow of Trinity College, president of the RIA and bishop of Limerick. (Count von der Schulenburg)

While Ranke was in Dublin there was a general election, which in Ireland returned 58 Liberal MPs against 47 Conservative. He thought that it was influenced by religious feelings, and the Presbyterian spirit, especially, astonished him. In Dublin the religious confrontation was much greater than in England:

‘During the last days in Dublin one heard of nothing else other than the elections for the next parliament. The parties remain in sharpest contrast more precipitously than anywhere else. Down in the bank, in the old parliament building, not far away from the statue of King William, we find pictures of his victory at the Boyne and of the heroes of that time (Schomberg and Walker) who freed the country of the tyranny of Catholicism. In the town hall O’Connell is especially glorified along with some of his ancestors who were able to shake the power of Protestantism. Between these oppositions the country is still moving.’

Ranke was interested in the election campaign. In England he had witnessed the speeches of several candidates but he soon realised that only religious questions evoked interest. Ranke described the Conservatives in England as the most ardent Protestants, while the Liberals were more papist. He attended a speech in a provincial town in southern England where every word of the speaker, a Mr Harper, against the Liberal ministry and the financial support of Catholic institutions, such as the college at Maynooth, was welcomed with applause. In a letter to a friend Ranke noted that ‘it seems like the times of King James are back again’. Overall, his observations suggest that Ranke had a greater interest in the cultural, historical and political development of Ireland than that of England.

By the banks of the Boyne

Ranke wished to see the place where he believed the fate of Ireland had been decided: the location of the Battle of the Boyne (1690). His interest is understandable since his latest volume of the History of England dealt with the years 1689–92, within which the Battle of the Boyne formed a central point of Irish and English history. Together with Charles and Robert Graves, Ranke made a trip to the Boyne on Saturday 8 July 1865. On their way they passed by the Hill of Tara, which ‘was the residence of the old kings whom all clan chiefs served’. When arriving at the River Boyne, which was, in Ranke’s opinion, ‘the centre of old Irish history’, they saw on the other bank the monument of Newgrange, ‘an artificial hill made from stones with a narrow entrance’. Charles explained to Ranke that in the centre was a large burial chamber. He knew of it because in his younger years he had entered it, although he admitted that no burial remains were to be found any more. He added that ‘it is here that St Patrick did his first conversion with the help of the river’, which was also ‘the scene of Old Irish poetry, which often included speeches between heroes and priests’. Ranke noted in his letter to his wife that ‘this, however, was not my main interest; rather I wanted to know more about the battle of the Boyne, which was to seal the fate of Irish history many years later’. At the river Ranke and Charles were welcomed by Mr Coddington, a relative of Charles’s who owned several fields in the area of the former battle. It was a warm, sunny day, and Ranke enjoyed the valley as ‘one of the most beautiful sights’ because ‘the trees lining the graceful river and the green meadows were unlike any I have ever seen before’. Together the visitors were shown the site of the battle, and they followed up the different movements of the armies on a map kept by Coddington. For Ranke this exercise was also history: following up his knowledge of the facts with a map and the actual site itself. Although ‘the area has since been altered by the building of a canal’, it was easy for him to follow the movements of the armies and to find ‘the forts, which were defended by one army and occupied by another’. Ranke was shown ‘the hill from which King James watched the battle and made a dash for freedom; the graves of the defeated, and the monument of the victors’. Besides this, Coddington related how the father of his great-grandfather’s carpenter had told of how he brought the corpse of Schomberg on his cart to Dublin, where he was laid to rest in St Patrick’s Cathedral. Ranke commented to his wife that such explanations were ‘a thread of a living tradition that was passed down to us from that time. I had good reason to often discard what I heard and somehow managed to convince my companions’. Ranke and Charles returned satisfied to Dublin.

Ranke visited many sites in Dublin. Friduhelm probably saw even more as he had more time to spare. His uncles Charles and Robert Graves showed him around Trinity College, Dublin Castle, the Royal Irish Academy, the Custom House, the old Parliament, the Royal Dublin Society, City Hall, the equestrian statue of William III, Fitzwilliam Square, Merrion Square and some churches. Ranke also recorded that he walked through a number of parks. A note in the visitor book of Marsh’s Library made by the keeper, Thomas Russell William Cradock, for Thursday 13 July records: ‘Two strangers to see Ly [Library]’. It is possible that these two strangers were Ranke and his son.

The plan to travel around Ireland and to Scotland was dropped, and Ranke returned to Cheltenham to continue copying documents. At this point the true historian showed his face: Ranke was not willing to let his latest and most precious treasure go that easily. During their second visit to Cheltenham, Ranke stayed almost all the time in Phillipps’s house examining documents. Friduhelm was asked to copy as much as possible, a task he very much disliked. The research trip to England and Ireland undertaken in 1865 is another example of Ranke’s constant search for ‘historical truth’, which actually postponed the printing of his appendix volume of the History of England by three years because of the new manuscripts in the collection of Sir Thomas Philipps.

The honorary degree from Trinity was of great personal significance to Ranke. He received many honorary degrees throughout Europe, but the first place in which he was honoured abroad was Ireland, the home of his wife’s family.

Andreas Boldt lectures in German and history at NUI Maynooth.

Further reading:

A. Boldt, The role of Ireland in the life of Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886): the historian and historical truth (Lampeter, 2007).

G. G. Iggers and J. M. Powell, Leopold von Ranke and the shaping of the historical discipline (Syracuse, 1990).

L. Krieger, Ranke, the meaning of history (Chicago, 1977).

L. von Ranke, Das Briefwerk (Hamburg, 1949).