The Hunger: the story of the Irish famine

Published in Issue 2 (March/April 2021), Reviews, Volume 29RTÉ1, 30 November & 7 December 2020

Tyrone Productions, directed by Ruán Magan

By Donal Fallon

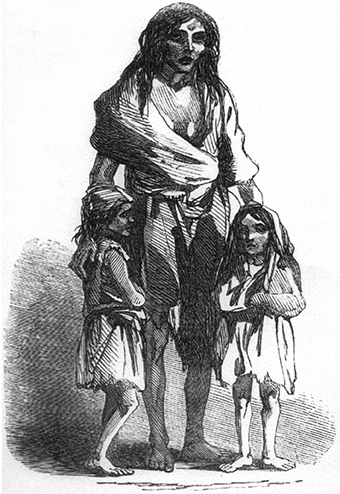

Above: Bridget O’Donnell and her children—one of James Mahony’s now-iconic and deeply familiar images of the Irish peasantry that shook the British public. (Illustrated London News)

The Atlas of the Great Irish Famine pre-dated the Atlas of the Irish Revolution by some five years, but the remarkable success of the latter has opened new doors for its forerunner. In many ways, The Hunger follows the same trusted formula of 2019’s The Irish Revolution, narrated by Cillian Murphy, which saw director Ruán Magan draw on the rich primary sources contained within that atlas, alongside a stellar line-up of historians, most of whom made the leap from printed word to screen.

Magan and Tyrone Productions had a more difficult task in telling the story of the calamity of the mid-nineteenth century. The archival vault, which produced British Pathé newsreels or moving images of a war-scarred Dublin for The Irish Revolution, was of little use in the telling of the story of the Great Hunger. And yet, in itself, this becomes part of the story early on. In some of the finest contributions to the two-part documentary, Emily Mark-Fitzgerald emphasised the importance of illustrations in shaping public discussion on the Irish crisis. In a rapidly changing media landscape, and in the days of the Illustrated London News reaching the peak of its political influence, James Mahony’s now-iconic and deeply familiar images of the Irish peasantry shook the British public—that is, until ‘famine fatigue’ set in.

That French rather than Irish is the second most frequently spoken language in this documentary says much about an editorial decision wisely taken; The Hunger sets the crisis in its British and European contexts, contrasting government policy here with that on the European mainland, where something in the region of 100,000 people lost their lives to the failure of the potato crop in the 1840s. This ensures that voices unknown to Irish ears, like that of historian Sylvie Aprile, bring totally new perspectives to the story. The Hunger works particularly well by bringing voices that are familiar to the table, too, like the authoritative Joe Lee, Christine Kinealy and Cormac Ó Gráda.

As UCC’s John Crowley has rightly noted, ‘television as a medium in ways demands an overarching narrative, one that always tidies away the messiness of history’. The Hunger, however, expertly manages to weave its way from London–Dublin politics to the reality of life on the ground in rural Ireland, utilising animated primary sources like the 1841 census to show the complexity and divisions of mid-nineteenth-century Ireland. There was not one collective experience of the crisis in Ireland; indeed, Breandán Mac Suibhne, author of the acclaimed The end of outrage: post-famine adjustment in rural Ireland, stresses the point that while many suffered, some profited.

Above: Emily Mark-Fitzgerald—emphasised the importance of illustrations in shaping public discussion on the Irish crisis. (RTÉ)

Liam Neeson—a naturalised American citizen since 2009—proves an inspired choice for a documentary that maintains international focus throughout, and undoubtedly will ensure significant international interest in the production. Neeson perfectly captures the tone throughout, as we hear his voice over Brian O’Leary’s shots of cityscapes and rural Ireland. The use of contemporary shots in historical documentaries has been more common in recent times, including RTÉ’s recent Bloody Sunday 1920. Here there is a function beyond just aesthetics in the use of drone and aerial shots, as the landscape of the crisis is still visible, and in sometimes surprising ways. From above we see stone walls, divided lands, mass graves and ‘famine roads’ (in many cases literal ‘roads to nowhere’, rooted in the economic thinking of the government, cross-examined throughout the two-part documentary)—reminders of the event still present.

Above: Joe Lee—a familiar and authoritative voice. (RTÉ)

The first part of The Hunger was billed as telling the story of the first three years of the crisis, but in truth it was as much an exploration of the road to 1845. It expertly traces the correlation between the arrival of the potato and rapid population increase in rural Ireland and explains Ireland’s place in the expanding British Empire. At a time of industrial revolution, Ireland was defined not by her industries but by the absence of them. An enormous peasantry, overly dependent on the potato, stood little chance in a jurisdiction where laissez-faire economic thinking came to dominate. There is a slower pace to the first episode, a masterful explanation of nineteenth-century Ireland in a broad sense, than to the second.

One crucial difference between The Irish Revolution and The Hunger was that, while the former was given three episodes in which to explain the journey to Irish nationhood, The Hunger attempts to tell the story of the pivotal event of modern Irish history in two. In just ten minutes of its closing episode, the post-Famine rise of the Catholic Church, the psychological effects of the crisis, the emergence of Irish America (including a snap of President Joe Biden) and the impact of the crisis on the revolutionary generation are briefly mentioned. It is difficult not to feel that the conclusion and impacts of the crisis are given less consideration than its origins.

Much discussion of The Hunger on social media centred on how it would address the issue of culpability. The inevitable but unenviable question of genocide in this case fell to Brendan O’Leary, professor of Political Science, who notes that while neglect, indifference to suffering and cold-heartedness to the fate of the Irish poor were present, the course pursued by the government of the day owed more to its unshakeable belief in free-market principles than to ethnic cleansing. O’Leary suggests the term ‘genoslaughter’ as perhaps more fitting.

An Gorta Mór scarred and shaped our island to a greater extent than any other event. As an event that brought some to the poorhouse and others to the White House, its impact is still felt in the contemporary world, but it is an event of such complexity as to be off-putting to even the most ambitious of documentary-makers. Ruán Magan has once again succeeded in bringing an enormous international story to our screens in a way that does not lose human emotion or the picture of life on the ground in rural Ireland.

Donal Fallon is a historian and the presenter of the ‘Three Castles Burning’ social history podcast.