‘The Cliona, the Maev and the Macha, the pride of the Irish Navee’

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2021), Volume 29A brief history of the Irish Naval Service.

By Daire Brunicardi

The naval provisions were an important part of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. The British Admiralty was forceful in its recommendation to government to prohibit the Irish Free State from having a navy. This was modified in the finally agreed Treaty under Article 6, which stated that ‘Until an arrangement has been made between the British and Irish Governments whereby the Irish Free State undertakes her own coastal defence, the defence of Great Britain and Ireland shall be undertaken by His Majesty’s Imperial Forces’, and Article 7, which left the British in control of the harbours of Cork, Berehaven and Lough Swilly and ‘such other facilities as may from time to time be agreed’ as well as ‘In time of war—such harbours and other facilities as the British Government may require’. The most apparent result was the continuing presence of British forces in the forts defending the strategic harbours. In addition, two Royal Navy destroyers were located in Irish waters until 1938, with mooring buoys in Cork Harbour maintained by the OPW for their use. A conference was to take place five years after the enactment of the Treaty to discuss Irish maritime defences.

The Coastal and Marine Service

Above: Marine Service officer Lt. Billy Richardson. While he was overseeing the delivery of a motor torpedo boat (M2) from J.I. Thornycroft on the River Thames in 1940, the boat was requisitioned by the Royal Navy for the Dunkirk evacuation. Richardson went with it but it only got as far as Dover, thus avoiding the potential diplomatic furore that his capture by the Germans might have caused. (Richard Ridgeway)

The Civil War marked the first attempt to form an Irish naval service. Various vessels had been chartered by the National Army in its prosecution of the war, notably for the landing of troops in Cork Harbour and some other ports. Several coastal cargo steamers were chartered as patrol vessels and transports. These were used for supplying army units and for carrying prisoners from ports around the coast to Dublin.

The naval dockyard on Haulbowline Island in Cork Harbour was handed over to the new government in 1923, along with a few small vessels. The most substantial was the large Admiralty salvage tug Dainty, armed with a twelve-pounder gun. Twelve minesweeping trawlers were purchased, as well as four fast, large motor launches, one of which sank on its way from England. A hastily assembled group of men of various maritime backgrounds was recruited to man this fleet, with a comprehensive document laying down organisation, uniforms, bases, signalling and many other matters. Established in spring 1923, the Coastal and Marine Service was under the command of Major-Gen. Joe Vize, with Capt. (nautical) Eamonn O’Connor as Marine Superintendent. Photographs and accounts of this force would inspire little confidence in it as a disciplined military or naval organisation, but, in fairness to those who served in it, its roles and purpose were vague and it did not last long enough to settle down and properly organise itself. By 1924 it had been disbanded and the vessels sold off. The only official Irish government presence left in Irish waters was the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries research and patrol ship Muirchu, formerly the Helga.

Lack of Irish interest

A preliminary informal meeting to discuss an Irish naval force duly took place in London in 1927. The British delegation proposed a fleet of minesweeping trawlers to keep clear the routes between major ports in time of war; anything more sophisticated would be ‘beyond the Irish state in starting a navy’.

There was nobody in the Irish delegation with any maritime or naval experience to offer counter-proposals, although a document had been drawn up by a Capt. Johnson of the National Army with an elaborate ‘wish list’ of naval vessels and supporting infrastructure. According to the late Col. Dan Bryan, the Irish delegation had no real interest in the matter. Their position was that any Irish naval force must be accompanied by the handover of the forts (Cork Harbour, Berehaven and Lough Swilly). This, of course, the British refused, and Bryan felt that it had been cynically introduced to defeat the purpose of the conference. The formal meeting was deferred and in fact never took place.

The Muirchu continued her solitary patrols, increasingly frustrated by the difficulty of catching and prosecuting infringements of fisheries legislation by foreign vessels. Frequent letters to the papers and questions in Dáil Éireann brought no response until 1936, when new legislation was introduced and a second patrol vessel was acquired, the deep-sea trawler Fort Rannoch. British destroyers continued coming and going from their mooring buoys in Cobh Roadstead. They were frequently in other harbours and anchorages around the coast, but what they were doing other than maintaining a presence and reporting intelligence is difficult to determine.

With the handover of the forts in 1938, the army general staff drew up another ‘wish list’ for a maritime defence force, consisting of a substantial fleet of patrol vessels, minesweeping trawlers and a fleet of 50 motor torpedo boats (MTBs). This, of course, was eviscerated by the Department of Finance, and in early 1939, as war appeared increasingly likely, it was announced in the Dáil that the government intended to buy some minesweeping trawlers and MTBs. Six boats were duly ordered from J.I. Thornycroft’s yard at Hampton on the Thames.

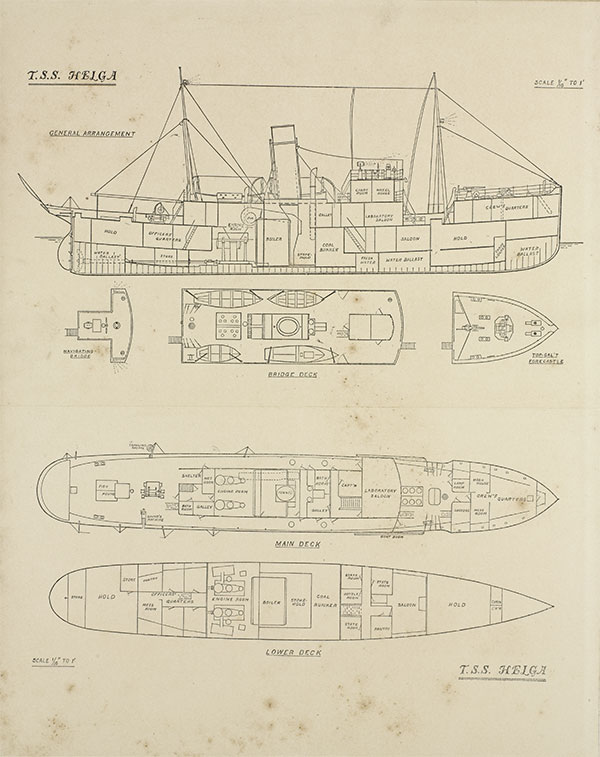

Above: Drawings of the Helga, which famously shelled Boland’s mill and Liberty Hall in 1916. In 1923 it was handed over to the Irish Free State’s Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and renamed Muirchu. From 1924 to 1936 it was the only official Irish government presence left in Irish waters following the disbandment of the Coastal and Marine Service, a motley collection of vessels and crew cobbled together during the Civil War. (NMI)

Irish Marine and Coast-watching Service, 1941

When war broke out in Europe in September 1939, the Irish state hastily had to put in place measures to comply with the Hague Convention for a neutral state in time of war. Apart from controlling shipping into its ports, it was obliged to prevent the use of its waters by belligerents. This required a naval or military force with government-commissioned ships commanded by commissioned and gazetted officers. Once again a hastily formed force was assembled from people with naval and marine experience. It was different this time, however, as a military cadre from the army gave it an organisational and disciplinary structure, and several ex-naval officers and NCOs provided the professional expertise. One of these was Seamus Ó Muiris, who had retired from the Royal Navy in 1922. He took command of the force in 1941. A coast-watching service was also established; these were grouped together as the Marine and Coast-watching Service but were separated in 1942.

By the time war broke out, none of the Irish MTBs had been built. One boat nearing completion, originally intended for Estonia, was instead sold to Ireland and named rather mundanely as M1. It arrived in Dún Laoghaire in spring 1940. Two others were nearing completion as the German armies rampaged into France. During the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk, M2 was requisitioned from the builders by the Royal Navy to evacuate some VIPs from France. An Irish Marine Service officer, Lt. Billy Richardson, went with it. One can imagine the political and diplomatic furore that would have arisen if he had been captured by the Germans. As it happened, the boat never got beyond Dover and was duly returned to the yard for completion and handover to the Irish. M3 was completed in summer 1940, but on her way to Ireland she was bombed by German aircraft near Portland Bill. Luckily, she sustained only minor damage and no injuries.

The two Department of Agriculture vessels, the Muirchu and the Fort Rannoch, were taken up by the Defence Forces in December 1939 and commissioned with the peculiar designation of ‘Public Armed Ships’. Their officers were commissioned and crews enlisted. Both were fitted with a twelve-pounder gun, some lesser weapons and radio, with extra crew for this.

This tiny force, which eventually consisted of six MTBs, two patrol vessels, a ‘mine planter’ (a small cargo ship) and a sail training ship and was manned by a force of about 300 officers and ratings, performed remarkably in the five years of the Emergency. One of its most critical and dangerous tasks was dealing with the large number of drifting mines from the extensive minefields laid by the British in the waters south of Ireland. There was a naval reserve of about 1,000, called the Maritime Inscription, located in the various ports.

Above: The LÉ Deirdre alongside three minesweepers, with crews formed up on the quay, after the arrest of the gunrunning ship Claudia off Helvic Head in March 1973. (Irish Naval Service)

Irish Naval Service, 1946

At the end of the Emergency the government and the Department of Defence had to decide what to do with the Marine Service. Morale had deteriorated as the war years progressed, and the chief-of-staff’s report on it in 1945 was scathing, but the experience of the war years prompted the government to take two initiatives in the maritime sphere—to maintain a ‘strategic fleet’ of merchant ships and to provide a proper naval force.

Strangely, Commander Ó Muiris was not brought into the discussions on the form of the new navy. Most of the Marine Service personnel were discharged, with only a small group of those who had joined for the war period retained. Also retained were the ex-Department of Agriculture and Fisheries personnel, as they had permanent government employee status, but the officers were sidelined and removed from the promotional structure within the new service.

The Naval Service was established in 1946 as a component of the permanent Defence Forces. A former Royal Navy officer, Commander H.J.A. Jerome, was employed to head the new service, with the rank of captain (equivalent to colonel in the army). Several other ex-Royal Navy personnel were also employed. Merchant service officers were recruited and sent for training in the UK. An option on six Flower-class corvettes was taken with the British Admiralty, three to be provided immediately. Vigorous recruitment and training took place to man the ‘new’ ships and operate the weapons systems fitted. Morale was high and the future looked bright. There were also plans for a hydrography survey vessel and a training ship.

Above: The LÉ Macha, one of the Flower-class corvettes acquired from the British Admiralty in late 1946, at sea in the late 1950s. (Luke Cassidy)

Hostility and indecision

The euphoria, however, didn’t last long. Changes in government and actual hostility to the new service within the Dáil, along with general indecision within government and the Department of Defence, resulted in a long period of decline. The additional corvettes were never acquired, never mind any other ships. The corvettes were in poor condition when purchased, but it is to the credit of the small naval dockyard in Haulbowline that they were overhauled and maintained and several substantial improvements made. Recruitment and retention were ongoing problems, even among the officer corps.

By 1968 most of the weapons, by now obsolete, had been removed from the corvettes. The ships were now purely fishery protection vessels. At this stage the army was undergoing a boost in morale and general conditions on the strength of United Nations service in the Congo and elsewhere. This boost, if anything, served to worsen the situation for the navy. Emphasis in defence spending was even more focused on army needs, and service in the Defence Forces for young men was more attractive in the army. It is to the credit of the remaining officers and non-commissioned officers of the Naval Service in those years that they continued to fight for their service in the face of neglect, apathy and even ridicule (e.g. the lyrics of the Dubliners’ 1968 song, ‘The Irish Navy’, referenced in this article’s title). There was even consideration being given to disbanding the service altogether. By the late 1960s the corvettes were being condemned one by one. Replacements were proposed and discussed, but foot-dragging and prevarication within government and the civil service led to the farcical situation where eventually there was only one serviceable ship. When this was undergoing refitting, the State’s territorial waters were ‘protected’ by an officer with a pistol aboard the fishery research vessel Cu Feasa.

Turn-around from near extinction

In 1971 three minesweepers were bought from the UK as a stopgap measure to replace the corvettes while new ‘all-weather’ patrol vessels were being built. The first, the Deirdre, was launched that year. Recruitment improved and officers from the merchant service were offered ‘direct entry’ commissions for three years with the possibility of permanency. With the commissioning of the Deirdre, the navy now had, and could man, four seagoing units. The minesweepers also provided a return to a naval function for the service, introducing a diving unit; while the minesweeping role lapsed, the naval diving unit became an essential part of the service. Credit for this rapid turn-around from near extinction goes to the late Commodore Thomas McKenna and the dogged persistence of his colleagues in the service.

The expansion of the navy was fortuitous, given the worsening situation in Northern Ireland and the spillover to the rest of the island. The arrest of the gunrunning ship Claudia off Helvic Head in 1973 brought home forcefully the need for a navy. Joining the EEC in 1973 was to have the greatest impact on the fortunes of the navy, and the new International Law of the Seas pushed the area of maritime responsibility out to 200 miles. New ships built in Ireland in the late 1970s and ’80s, and two purchased from Britain, saw the fleet size increase to eight vessels. In due course a government commitment was given to maintain the fleet size at not less than eight and this has been maintained, with older ships being replaced as necessary. Several seizures of illegal drugs and the thwarting of another high-profile gunrunning attempt reinforced the positive attitude towards the service.

The fortunes of the Irish Naval Service continue to fluctuate, but it is now accepted as a well-established and professional State service. It confirms ownership of the large area of the North Atlantic which Ireland claims and for which it has responsibility. It also helps to extend Ireland’s influence abroad, with ships ‘flying the flag’ as far away as China, Japan, the United States and South America. The Navy’s recent participation in the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean and its deployment in assisting in dealing with the COVID crisis demonstrated its professionalism and versatility. It is a far cry from the sad days of the 1960s. The Dubliners’ satirical ballad has been well and truly put to rest.

Daire Brunicardi is a retired Senior Lecturer in the National Maritime College of Ireland, MTU.

FURTHER READING

T. McGinty, The Irish Navy: a story of courage and tenacity (Tralee, 1995).

A. McIvor, A history of the Irish Naval Service (Dublin, 1994).