Post-independence perspectives on ‘Irishness’ and identity

Published in Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2021), Volume 29

By Raymond M. Keogh

Above: President Michael D. Higgins—in 2012 he called for a ‘huge debate’ to redefine ‘Irishness’ in a manner that ‘is … appropriate for a real republic’. (Áras an Uachtaráin)

“For historians, the objective definition unburdens them of the impossible task of trying to reify Irish identity from the ever-changing narrative of its people or visualise it through the whims of shifting political and cultural perspectives over time.”

Four years before the anniversary of the Easter Rising in 2016, President Michael D. Higgins called for a ‘huge debate’ to redefine ‘Irishness’ in a manner that ‘is … appropriate for a real republic’. Why did he feel that this was necessary?

It only takes a cursory examination of the topic to understand why a redefinition of Irish identity is imperative. Whenever the subject is broached the responses are inadequate. This is true irrespective of whether the discussion takes place in a pub, through the media or in the halls of academia. If we don’t find answers now, the same questions will continue to be regurgitated and the same inadequate responses will be echoed back. There is, therefore, a pressing need to end—once and for all—this Groundhog Day cycle. Clearly, the president’s call requires an adequate response.

Disparate views

The visionary romantics of the early Irish state, as exemplified by Éamon de Valera, envisaged a singular Gaelic nation with one history, one faith and one language. The story of perspectives on ‘Irishness’ from independence to the present day could be summarised crudely as an ongoing war of attrition against the view of a pure unitary Irish race. Literary critic Declan Kiberd expresses this in his Inventing Ireland: the literature of the modern nation (1996). A change in metaphor summarises his entire thesis. The unitary green flag of the visionaries that wrapped Cathleen Ní Houlihan was replaced, in the minds of the writers, by a quilt of many colours.

Former patriotic romantics and Irish writers are not the only ones who have something to say about the country’s identity. Historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, social scientists, genealogists, journalists, contemporary politicians and the general public have all made contributions. Views differ widely.

Some archaeologists and genealogists still point to a basic underlying ethnicity. On the other extreme are anthropologists like Thomas Wilson and Hastings Donna, who in their 2006 book The Anthropology of Ireland express the view that Irishness can never be fixed. It must be negotiated, questioned and affirmed according to societal, historical and political contexts. What counts for Irishness depends on how the many different groups that make up the population of Ireland interpret its meaning. Irishness is fragile, shifting, relational, ambivalent and context-dependent, and each group comes with its own competing claim to authenticity.

Amongst the general public, views diverge in a different direction. At the time of the 1916 commemorations in March 2016, the Irish Examiner columnist Joyce Fegan provided a cross-section of opinions from a selection of Irish people. Several limitations were acknowledged, such as having continued poverty, homelessness and some marginalised groups in the country. Nevertheless, to be Irish, they felt, generally generates pride, pleasant memories, good feelings and great conversations. The Irish have a superior sense of humour. They don’t take anything too seriously. They are skilful in the use of everyday words, can speak on any topic and are hospitable and welcoming like no one else. They are known for fairness and acceptance of difference, are great with disabled people and are open to what’s going on all around the globe. They are the best sports supporters. They are well regarded and appreciated all over the world. They have a rich history; they promote peace; they build bridges—all in all, they are a sound bunch.

Time to reach for big green hats or to cringe in silence?

Cork hurler Seán Óg Ó hAlpín—‘… his father from Fermanagh, his mother from Fiji, neither renowned as hurling strongholds …’, as famously noted by sports commentator Mícheál Ó Muircheartaigh. Modern Ireland requires a radically new vision of ‘Irishness’ to accommodate a new society. (Irish Sun)

Search for a solid foundation

Individual citizens and professionals all place emphasis on different aspects of Irishness in accordance with what they understand the term to mean. When people encounter a statement about Irish identity it normally appears to make perfect sense. Unfortunately, all who delve into the subject are guilty of one glaring omission: nobody is willing to define what is meant by the expression.

This is not surprising; after all, the word ‘identity’ is suffering a crisis of meaning. And if it’s not possible to define identity, then it’s not possible to define the composite expression ‘Irish identity’. The only way to attain a comprehensive understanding of the term is to make a complete break with present approaches and return to the kernel of the problem. In other words, it is imperative to face the main challenge and to re-examine what—precisely—is meant by ‘identity’. This shifts the entire tenor of the debate and focuses attention on ‘identity’ itself.

There is no doubt that ‘identity’ is a complex matter and it is important to resolve its ambivalence. At stake are more than academic arguments. Identity goes to the heart of who we are, how we regard ourselves and how we behave. Our quest for identity is our most worthy undertaking because belief in who we are influences all we do and who we become. Therefore the problem can only be solved by deriving an objective definition of the term that is workable in practice.

Redefining identity

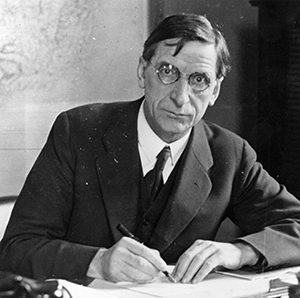

Above: ‘The Ireland that we dreamed of …’—visionary romantics of the early Irish state, like Éamon de Valera, envisaged a singular Gaelic nation with one history, one faith and one language. (Getty Images)

What makes you and me the same person over time despite all the transformations that we experience? We know that the chemical constituents of our bodies are continually changing. So, am I the same person as I grow? Social scientists find this to be an impossible conundrum to solve (consider the Ship of Theseus). Without doubt, in the quest for answers, we are seeking something that makes us unique. By implication, we also assume a component of constancy or ‘sameness’ at all times or under all circumstances in who we are, otherwise we would remain uncertain about our nature. Unfortunately, despite the origins of ‘identity’, which comes from the late sixteenth-century Latin identitas or idem, signifying ‘sameness’ or ‘same’, modern interpretations often diverge from this meaning. Professor of sociology Rogers Brubaker and historian Frederick Cooper in their seminal paper ‘Beyond “Identity”’(2000) acknowledge the awkwardness that arises when continuing to speak of identity while repudiating the implication of ‘sameness’ that it contains. Fortunately, relatively recent scientific discoveries have rescued the original meaning.

It is now clear that our individual DNA sequences are unique. Even so-called identical twins are not really identical. Besides, a DNA fingerprint is the same for every cell, tissue and organ of our body, with a few exceptions (like gametes, some white blood cells and brain neurons). Our basic DNA blueprint is present in our first cell (the zygote) and remains the same at every step of life until the death of the organism. In other words, DNA reveals what is meant by ‘sameness’ in who we are, were and will be despite all transformations. We are one and the same person at every moment of our lives.

Collective identity

Personal identity is the product of reproduction that generates new and unique DNA sequences. In other words, the identity of the individual emerges from a male and female who have—in their turn—originated from the wider human genome of our species. And the origin of that genome can be traced to a point some 200,000 years ago in Africa. Our forebears emerged from a critical bottleneck that marks the beginnings of the first modern humans. Our common origin within a relatively small number of people and the narrowness of the make-up of the genome itself (despite the possibility of some now-extinct Neanderthal additions) are marks of uniqueness in the human genome. In addition, our ability to reproduce universally confirms that there are no innate divisions in mankind. Reproduction is the unique characteristic that provides collective ‘sameness’ (i.e. identity) to the group. This conclusion has profound implications.

Collective or communal identity is fully satisfied at the species level and only at that level. Genetics is the new classifier. And human genetics do not correlate well with the normal divisions of humanity such as race, ethnicity, culture or nation. So-called ‘races’, ethnicities and cultures blur into each other when examined from the perspective of DNA. Nations are, by and large, artificial segments of territory on the globe’s land mass and contain few, if any, collective genetic traits that distinguish people within their borders from those outside.

In summary, what may be called objective, scientific or universal identity can be defined as the sameness of a person or group at all times or in all circumstances; the condition or fact that a person or group is itself and not something else (based on the Oxford English Dictionary).

Benefits

Above: Identity goes to the heart of who we are, how we regard ourselves and how we behave.

The change in paradigm is fundamental because it shifts perspectives of identity from subjective views of ourselves to an objective foundation based on human genetics. For starters, it raises the question: if our personal identity is a function of our DNA sequences and our communal identity is defined at the species level, where does the notion of ‘Irish identity’ fit in? The simple answer to the obstinate question ‘What is Irish identity?’ is that there is no such thing.

‘National identity’ does not exist in strict terms because it defies the ability to be defined. Nations are conceptualised within artificial geographic borders. They are subject to change in terms of the individuals and groups (read ‘sub-groups’) that inhabit them, as well as their associated characteristics. In other words, no innate ‘sameness’ exists at all times or in all circumstances within national frontiers. Problems always arise when those who belong to a nation, like Ireland, try to find some unchanging or common characteristics that identify the whole group within its synthetic borders. It is a futile exercise and can only lead to endless unresolved discussions, as is currently the case.

Despite the need to make an initial and profound mental adjustment, the benefits of applying the objective meaning of identity are enormous. The overwhelming benefits accruing from this change are compelling arguments in its favour: the standardisation of the meaning of ‘identity’ across all disciplines; linguistic precision; the achievement of an important inroad against subjectivity in the social sciences; knowledge that every person has a unique unchanging identity that cannot be removed despite the vagaries of life (we may experience difficult times but we cannot have an ‘identity crisis’ or lose our identity); and reinforcement of the notion of oneness in the entire human family.

The universal definition of the term represents a change in paradigm of several orders of magnitude and gives us power to create an ‘identity landscape’ that correlates perfectly with our human condition rather than depending, as we now do, on ever-changing subjective views, feelings and opinions about the people amongst whom we exist. This does not mean that we cannot interweave our emotions (including our historical perspectives, feelings of comradeship, familiarity, fraternity, patriotism etc.) into the nation to which we belong, but emotions and perspectives have little to do with identity.

For historians, the objective definition frees them from the impossible task of trying to reify Irish identity from the ever-changing narrative of its people or to visualise it through the whims of shifting political and cultural perspectives over time. The universal definition is a revolutionary answer to the president’s call and a far cry from traditional viewpoints. On the other hand, Ireland prides itself in being a progressive nation. It has welcomed radical cultural change in recent times. Besides, the scientific view of identity is the culmination of a historical trend that has been taking place since the middle of the twentieth century at least. The shift from the insular vision of a unitary Irish race in the early years of the state to a fully cosmopolitan view on the anniversary of independence reaches its ultimate expression in universal identity. It forces us to replace Kiberd’s patchwork quilt with a more inclusive metaphor. His multicoloured rug should be superseded by a modern Venn diagram of national and international influences.

Perhaps the greatest advantage of the new perspective is that it provides a revolutionary way to understand and accept the modern phenomenon of migration. Within the objective view of identity, ‘Irishness’ can never be threatened by an injection of migrants because universal identity implies that human culture itself is singular but diverse. Furthermore, the universal view of identity is robustly accommodating and is therefore appropriate for understanding our society in whatever way it may develop in the long term. In addition, it challenges the most insidious forms of ‘identity politics’. In short, its logic helps us to live together in tolerance of each other, something that is badly needed in our contemporary world.

Raymond M. Keogh is director of Our Own Identity and author of Shelter and shadows (2016).

FURTHER READING

R.M. Keogh, ‘DNA and the identity crisis’, Philosophy Now 133 (2019).

P. Logue,Being Irish: personal reflections on Irish identity today (Cork, 2001).

J. Waters, Was it for this? Why Ireland lost the plot (London, 2012).