CONQUEST: Eleanor, Countess of Desmond (1545–1638)

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2021), Volume 29A forgotten heroine of the Tudor Wars.

By Anne Chambers

‘Out of every corner of the woods and glens they came creeping forth upon their hands for their legs could not bear them, they looked like anatomies of death, they spoke like ghosts, crying out of their graves … in a short space there were none almost left and a most populous and plentiful country suddenly left void of man or beast.’

So the English poet Edmund Spenser described the province of Munster in the year 1583. While the dreadful spectacle of famine, death and decay may have appalled his eyes, Spenser, together with his friends, such as the famous explorer Sir Walter Raleigh, had actively participated in and personally benefited from Munster’s ruin, as the English Crown wrested the province from the grip of its once-powerful overlord—Gearóid (Gerald) Fitzgerald, 15th earl of Desmond.

Dogs of war let loose

By 1579 the writing was on the wall for Desmond. He was rooted in the feudal tradition of a bygone era, from which he derived his status and wealth, but the world outside his Munster domain had moved on. Queen Elizabeth I of England viewed him as a threat to her power in Ireland, his intrigues with Spain as a threat to England’s security, and the vast acres under his control in Ireland as a potential goldmine. After years of prevarication, in 1579 Elizabeth finally let loose the dogs of war. Desmond was proclaimed a traitor, a price on his head and his lands and numerous castles up for grabs.

For three years a savage military campaign was waged against him by Elizabeth’s generals, aided by the earl of Ormond, Elizabeth’s Irish cousin and, ironically, Desmond’s stepson, as well as his bitter rival for power in Ireland. Abandoned by his Spanish allies, ill from dropsy and dysentery, too weak to even mount his horse, Desmond was hunted like a wild animal across the despoiled acres of his vast Munster lordship. Despite his overwhelming liabilities, however, he had one remaining asset—his countess, Eleanor.

Eleanor

Educated, intelligent, courageous and able, the daughter of Edmund Butler, Baron Dunboyne, from Kiltinan Castle, Co. Tipperary, Eleanor’s destiny was as a wife, mother and chatelaine. Instead, her marriage in 1565 to the earl of Desmond hurled her into the maelstrom of a bitter family feud, international political intrigue, a religious war, the enforced rebellion of her husband and, finally, social and political meltdown, destitution and ostracism.

With amazing skill, courage and diplomacy, Eleanor at first tried to negotiate with the English queen and her administration. Her letters are pragmatic, astute and knowledgeable, as she tried to keep at bay avaricious officials in the queen’s pay in Ireland, predatory English generals, disgruntled vassals of the once-powerful earl and power-hungry rivals from within his own family—all of whom hoped to profit from his downfall. During her husband’s previous lengthy imprisonment in the Tower of London she had single-handedly and capably administered his vast and far-flung lordship, stretching from the Decies in Waterford to Dingle in west Kerry. Enduring imprisonment herself, both in Dublin Castle and in the Tower of London, and exile in the slums of Southwark, her only son held hostage in the Tower, her mission—to save the house of Desmond, her husband, her children and herself from annihilation—became Eleanor’s obsession.

Above: Kiltinan Castle, Co. Tipperary, where Eleanor was born to Edmund Butler, Baron Dunboyne, in 1545. (Lord and Lady Lloyd Webber)

On the run with her husband

When her efforts as a mediator between her husband and Queen Elizabeth were overtaken by international events, and her husband declared a traitor by the English administrators in Ireland (with an eye to the potential advantages accruing to themselves from the confiscation of his extensive estates), Eleanor joined Gearóid on the run across the wastelands of his former Munster lordship. Enduring a knife-edge existence in desolate, hastily erected shelters in forests and mountains, she desperately tried to keep her husband alive until either the vacillating English queen called off her war dogs or help came from her husband’s fickle ally, King Philip II of Spain.

For three long years there was to be little respite for the ‘rebel’ earl of Desmond, his countess and their few remaining loyal adherents:

‘Like deere they laie upon their keepings and so fearfull they were, that they would not tarrie in anie one place anie long time but where they did dress their meate, then they would remove and eat it in another place to lie.’

With a price on her husband’s head, danger lurked everywhere. Constantly on her guard, Eleanor (an accomplished horsewoman) rode ahead of the little band of fugitives, ready to sound the alarm at the first sign of danger. To deter pursuing English scouting parties, like the lapwing she led them on many a wild goose chase away from her husband’s hiding place. ‘We had the Countesse of Desmond in chase two myles,’ the captain of the English garrison in Kilmallock (a former Desmond-owned castle) reported, ‘and myssinge herselfe took a great prey of three hundred kyne from her.’ From deep within the wilderness of the Glen of Aherlow and the Galtee Mountains to the outposts of the ancient Desmond palatinate of Kerry, the once most powerful man in Ireland and his faithful countess fled for their lives.

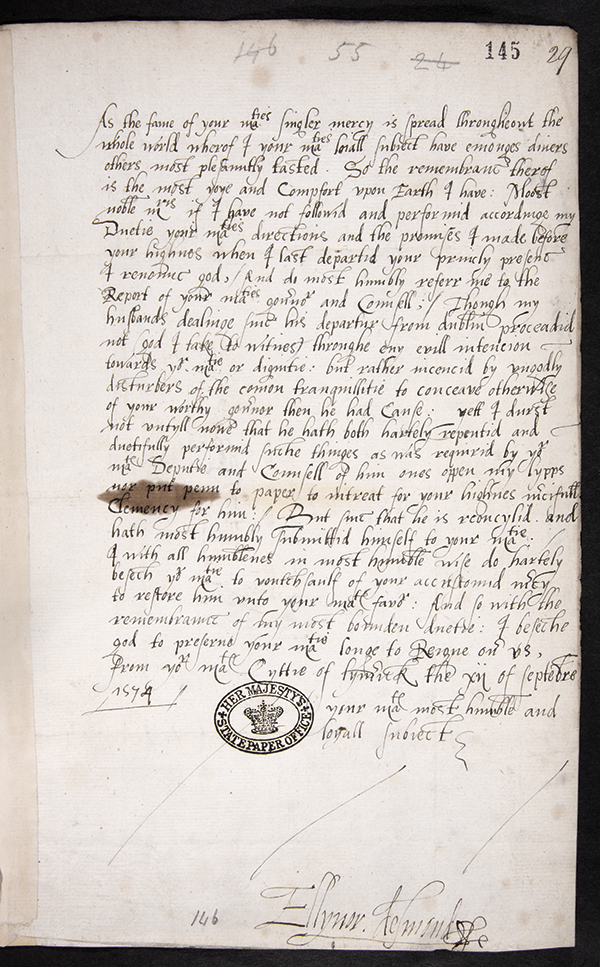

Above: A letter dated 12 September 1574 from Eleanor to Queen Elizabeth I, pleading that her husband’s escape from Dublin Castle the previous year was not ‘through any evill intencion to yor Majestie’. (State Papers, Public Record Office, London)

Run to ground and beheaded

When Gearóid was finally run to ground and ignobly beheaded in a lonely cave near Tralee, Co. Kerry, in the winter of 1583, his head pickled in a wine cask and sent to London to end up on a spike over the entrance to the Tower of London, Eleanor set out to salvage what she could from the ruins of her husband’s once-vast estates. Deserted as the wife of a ‘traitor’ by family and friends, a political and social outcast, pocketing her pride, she was forced to beg her bread with her five young daughters on the streets of Dublin. In one of her letters to the queen’s secretary of state, Lord Burghley, she described her extreme circumstances:

‘At the present tyme my miserie is suche that my children and myselfe liveth in all wante of met, drinke and clothes, having no house or dwellinge wherin I with them may rest, neither the aid of Brother or kinsman to relieve oure necessitie which is so miserable that I see my poore children in manner starve before me’.

At the English court

Above: Eleanor’s tomb, Sligo Abbey—she died in 1638, aged 93. (Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government)

Despite the concerted efforts of English officials in the Dublin administration, determined to protect their avaricious claims to Desmond’s confiscated estates and prevent his widow from presenting her case at the English court, towards the end of 1587 Eleanor, pawning everything she possessed, managed to escape to London to try and appeal her case directly to Queen Elizabeth. After experiencing humiliation and isolation in the outer environs of the Machiavellian Elizabethan court, her persistence and courage finally paid dividends when she was accorded an audience with the queen. Despite Elizabeth’s long-held animosity towards Eleanor’s late husband, the queen sympathised with her plight:

‘Wee having compassion of hir unhappie and miserable estate whereunto she is fallen, rather by hir said husband’s disloyaltie, than by anie hir owne offence, are pleased for hir owne reliefe to bestowe on hir a yearlie pension of two hundredth pounds sterling to be paid to hir yearlie out of our exchequer.’

It was also at the English court that Eleanor later found the love and protection of a new husband, Sir Donagh O’Connor Sligo, chieftain of County Sligo, to where she moved on their marriage in 1597. On Sir Donagh’s death in 1609 she was once again forced to defend her husband’s estates, this time to rebut the spurious claims made to his property in the courts of chancery, in both Dublin and London, by the new wave of English carpet-baggers and planters who descended like vultures on the unprotected lands of County Sligo after the fall of Gaelic Ireland in the years following the Battle of Kinsale (1601) and the Flight of the Earls (1607). With extraordinary courage and persistence Eleanor met the new challenge head-on, travelling on numerous occasions to Dublin and to London to defend, and mostly win, her case. She died in 1638, aged 93.

Conclusion

The life of Eleanor, Countess of Desmond, is testimony to the struggle of a courageous, spirited and enduring woman who refused to abandon hope in the face of immense personal tragedy against the background of an inexorable period of unparalleled destruction and upheaval in Ireland, which sucked an entire civilisation into its maw. In life Eleanor received few bouquets and in death oblivion from written Irish history, even from popular folklore. In the quiet ruins of Sligo Abbey her tomb, embellished with the heraldic emblems of her Butler, Desmond and O’Connor connections, stands as the only memorial to this unsung heroine of the Tudor Wars in Ireland. Its inscription reads:

‘Is that Penelope, Elinor, that second chaste Judith,

Indeed buried beneath marble stones?

I, Mother Irene, who with moistened cheeks stretch forth

My arms in redoubled lamentation.’

Held in archives in Ireland and England, however, Eleanor’s prolific correspondence with such iconic figures of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as Queen Elizabeth I, Sir Henry Sidney, Sir William Cecil, Sir Francis Walsingham, Sir John Perrot, Sir Robert Cecil and King James I bears witness to the character of this exceptional woman on whom fortune seldom smiled but who steadfastly refused to succumb to the dark shadows that relentlessly clouded her long life.

Her only son, James, a tragic prisoner in the Tower of London for almost all of his life and whom Eleanor was occasionally permitted to visit on her journeys to the city, died there in 1601, allegedly by poison, at the age of 30. Eleanor’s third daughter, Lady Katherine FitzGerald, married her first cousin, Maurice Roche, Viscount Fermoy. Through the Viscount Fermoy line Eleanor’s descendants include the late Princess Diana and her sons, Princes William and Harry.

Anne Chambers is the author of Eleanor, Countess of Desmond, 1545–1638 (Gill Books, 2011).