KINDRED LINES

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2020), Volume 28Tracing Black, Asian, Minority-Ethnic (BAME) and mixed-race people in Ireland c. 1700–1922, part I

By Fiona Fitzsimons

From at least the eighteenth century there were BAME people in Ireland and Britain. Recent scholarship has begun to ask questions about who these people were, where they came from and how they circulated. From the Classical Age the Mediterranean was a cross-cultural space; after 1450, overseas exploration and colonial traders created pathways between Europe and other continents. By 1700 BAME people in Europe had more than one origin: many were Europeans descended from an earlier generation of immigrants who assimilated; others were visitors travelling directly from their home countries for work, pleasure or opportunity (diplomats, travellers, merchants, skilled tradesmen in high demand); some were settlers or descended from settlers in British overseas territories, ‘returning’ to the home countries, of which Ireland was one; and some were slaves, transported with the household appurtenances as the families they served moved about.

W.A. Hart estimates the numbers of BAME people in Ireland at between 1,000 and 3,000 in the second half of the eighteenth century, and he reckons that most of these were servants or slaves. Hart’s figures are taken from a representative survey of contemporary newspapers and Church of Ireland parish registers in towns and cities, including Dublin, Belfast, Cork, Kinsale and Waterford, with an inevitable selection bias towards Ireland’s city-ports.

Digitisation has delivered a dividend of tens of millions of records published online. We can search quickly and accurately across a wider range of sources than Hart used. It’s possible to find further evidence of BAME people in Ireland living outside the cities in a wider set of circumstances.

We still have a problem in that in Ireland and Britain most historical records don’t inquire into race or ethnicity, with the notable exception of the books of ‘Negro Pensioners’ (1702–1876) in the Royal Hospital, Chelsea. So how do we find people of colour in the records? One method is to use cultural signifiers—name, religion and country of birth. It’s highly probable that Ayah Kumaria (a Hindu born in India), Kwasyuen Tsan (no religion, born in China) and Haroon Batmazian (a Congregationalist born in Turkey) were not white Europeans, but what happens when cultural exchange and assimilation eliminate difference, when Wai Ming Tai becomes Bernard Tighe?

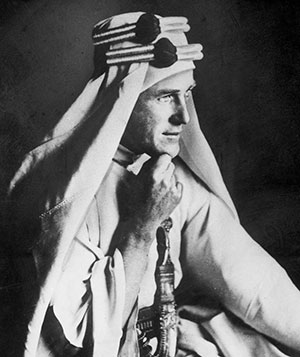

Above: The archives of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) have probably the most complete evidence for the presence of activists, including Frederick Douglass, in Ireland.

We find BAME people in Ireland in the records of the armed services, as well as in institutional records (hospitals, workhouses, prisons), which provide a physical description of every recruit or inmate. They are documented in the records of people who became denizens. If we extend our search of church records, we find them in Catholic registers, including country parishes. In the Registry of Deeds we find evidence of families involved in plantation slavery, including many of Irish and mixed-race heritage. The archives of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) show organised opposition to slavery—and have probably the most complete evidence for the presence of activists, including Frederick Douglass, in Ireland. Finally, given our history of emigration, we find Irish-born people of BAME heritage in overseas records.

The reality is that Ireland was an integral part of the British Empire. Empires are multi-cultural and extremely diverse. It’s possible that Ireland was more diverse in the two centuries before independence than after 1922.

In the next issue, I’ll consider some case-studies.

Fiona Fitzsimons is director of Ennaclan, a Trinity campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.