Gregory and the Swanzy riots, 1920

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2020), Volume 28The contrasting fortunes of Lisburn’s two RIC district inspectors.

By Ciaran Toal

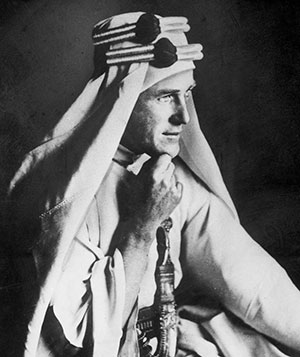

Above: County Inspector Vere Gregory, a cousin of Lady Gregory, the folklorist, writer and companion of W.B. Yeats. (Irish Linen Centre and Lisburn Museum)

On 19 August 1920, the magistrates for County Antrim gathered in Lisburn’s courthouse, gifted to the town by Sir Richard Wallace (1818–90), to present an inscribed plate to Mr Vere Gregory (1871–1957). For ten years Gregory had served as RIC District Inspector (DI) in Lisburn, witnessing strikes, elections, the rise of the Volunteers and even a bomb planted by local suffragettes (see HI 22.6, Nov./Dec. 2014, ‘“The brutes”: Mrs Metge and the Lisburn Cathedral bomb, 1914’). After a brief sojourn in Tralee, Co. Kerry, he had been promoted to the rank of County Inspector (CI) for Derry.

In making the presentation, the chairman, George H. Clarke, a prominent unionist and director of the Island Spinning Mill, praised the former DI for preserving one of the province’s most peaceful towns and filling ‘his important position without giving offence to anybody’. Local magistrate James McConnell wished Gregory well and expressed a hope that he would be spared and come through the present troubling times in Ireland, while Robert Griffith JP thanked the CI for the way he discharged his duty ‘without fear or favour’. Gregory was ‘an officer of outstanding ability’.

Last to address the crowd was the new DI for Lisburn, Oswald Ross Swanzy (1881–1920). He congratulated Gregory on his promotion and assured him that his former colleagues were ‘sorry to lose him’. In closing his brief remarks, Swanzy ‘considered Mr Gregory was lucky in the magistrates he had to deal with in Lisburn’. This innocuous remark won the room, which erupted in laughter and applause. But why?

The murder of Tomás MacCurtain

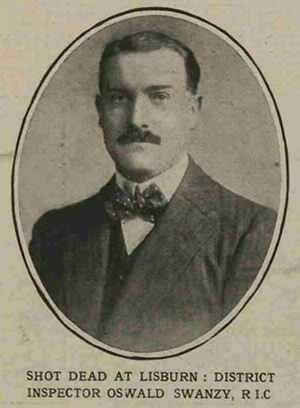

Above: District Inspector Oswald Ross Swanzy. Born in Monaghan, Swanzy joined the RIC in 1905 and served in Cavan, Limerick and Carlow before his appointment to Cork. (Irish Linen Centre and Lisburn Museum)

Swanzy had taken up his appointment in Lisburn in mid-June 1920 with a very public murder charge hanging over his head. In March the lord mayor of Cork, Tomás MacCurtain, had been murdered in his home by a gang of men with blackened faces, largely believed to be RIC, and Swanzy was DI for the North District of the city where the murder had taken place. An inquest was set up to investigate MacCurtain’s assassination, and after weeks of sensational testimony the jury delivered a verdict of ‘wilful murder’ against a swathe of agents, from Prime Minister Lloyd George down to DI Swanzy and ‘unknown members of the RIC’. MacCurtain’s death was believed to have been revenge for the increased targeting of RIC men in Cork.

Was Swanzy guilty? Did he send out a murder gang to assassinate the lord mayor? There is no smoking gun, although eyewitness testimony placing men from King’s Street RIC barracks in the vicinity of the murder, and the discovery of spent police cartridges and RIC buttons at the scene, points to a constabulary rifle having fired the fatal bullet. Shortly before the murder, the same body of men had been seen talking to a man fitting Swanzy’s description—5ft 8in. to 5ft 10in. in height, with a ‘pale complexion, dark moustache’, who ‘wore a dark overcoat with a velvet collar and soft hat’—close to the DI’s apartments on Patrick’s Hill. Swanzy gave an unconvincing performance at the inquest, while evidence from police in Cork was vague and evasive. The force was found to keep poor records. Barrack diaries, for example, failed to record parties of policemen who streamed out of local stations to attack several Sinn Féin clubs in Cork following the attempted murder of DI MacDonagh on 10 March 1920. Swanzy, it was publicly known, had led one of the raiding parties.

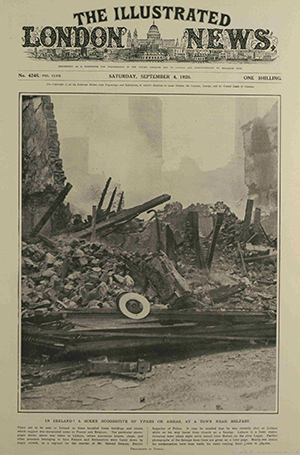

Above: ‘A SCENE SUGGESTIVE OF YPRES OR ARRAS AT A TOWN NEAR BELFAST’—Lisburn in the wake of the Swanzy riots of August 1920. (Illustrated London News, 4 September 1920)

Swanzy in Lisburn

Following the inquest Swanzy was a marked man, and he was moved north to Lisburn, a unionist town, for his own safety. CI Gregory had also served in Munster. In his address to the gathered magistrates on 19 August 1920, he recalled that in his short time in Kerry he had on three occasions had to view the body of one of his men who had been murdered for ‘doing their duty’. This, he claimed, was in stark contrast to south Antrim, where there ‘never was the slightest conflict between the police and any section of the community’. Gregory used his presentation to congratulate Swanzy on his appointment and wished him well.

The new DI, however, had little luck in Lisburn. Three days after the presentation, Swanzy was assassinated in the centre of the town by Volunteers of the Cork IRA. In the days that followed, Gregory’s ‘peaceful town’ was raked by vicious rioting, local businesses were burned and looted, and several hundred Catholics fled, some never to return. The army was called in to quell the rioting, which spread to Belfast. The burning of Lisburn came at the tail-end of a tumultuous summer in east Ulster, in which loyalist rioting in Banbridge, Dromore and Newtownards reflected a growing anxiety that the Protestant north was under attack.

The aftermath

DI Swanzy’s cortège quietly left Lisburn for burial in Mount Jerome Cemetery, Dublin, on the morning of the third day of riots. The funeral was small and poorly attended in comparison to the noise and violence provoked by his death.

By contrast, CI Gregory served in Derry until 1922 and was chairman of the RIC Officers’ Representative Body. He argued for full disbandment of the RIC after the Truce and was concerned with the well-being and livelihoods of the rank and file. After retiring to Donegal, and later England, he earned his LLD from Trinity College, Dublin, and published the genealogical-biographical The House of Gregory in 1943. The book reflected, in part, on his career in the RIC, particularly his experience in the West during the 1916 Rising and policing during the War of Independence—‘a black chapter’ in the history of the British Empire. Curiously, Gregory made no mention of the burning of Lisburn or the assassination of his successor. He only wrote of his regret at the war’s ‘competition in murder’.

Gregory’s quiet retirement contrasts sharply with the legacy of DI Swanzy. In Cork, Swanzy’s name became synonymous with a dirty war of State murder and reprisals, while in Lisburn the spectre of the riots still looms large in the collective memory—‘Swanzy’, ‘pogroms’ or the ‘troubles of the ’20s’ are still whispered under the breath in parts of the town to this day. His murder also cast a long shadow over the local police. Following the removal of a tricolour by the RUC in Aghalee, outside Lisburn, in 1935, the RUC received a handwritten letter from the local IRA urging them to ‘Remember the shooting of Swanzy in Lisburn. We got him and we will get you all.’

Ciaran Toal is Research Officer with the Irish Linen Centre and Lisburn Museum.

FURTHER READING

P. Lawlor, The burnings (Cork, 2009).

C. Magill, Political conflict in east Ulster, 1920–22—revolution and reprisal (Belfast, 2020).