‘The Champion Kiely’—Ireland’s greatest athlete?

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2019), Volume 27His personal bests remain competitive in the 21st century.

By Christopher Warner

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Tom Kiely, possibly Ireland’s greatest athlete. His sporting career included 53 national wins, two world titles and an Olympic gold medal in the ‘all-around’ (forerunner of the decathlon), while setting numerous world records along the way. In addition, his versatile talents saw him captain the Grangemockler Gaelic football team and represent Munster in hurling—all of which contributed to his well-deserved moniker, ‘the Champion Kiely’.

Thomas Francis Kiely was born on 25 August 1869 in Ballyneale, just outside Carrick-on-Suir. As the oldest son of William Kiely and Mary (née Downey) in a family of ten children, young Tom grew up working on the farm, building strength and stamina that would later serve him well. He also benefited from top-notch mentoring by fellow Tipperarians the Davins, Ireland’s ‘first family’ of athletics, led by Maurice Davin, a founding member of the GAA. After finding success in local competitions, Kiely’s breakthrough season came in 1892. He captured his first Irish Athletic Amateur Federation (IAAF) championship in the all-around, a gruelling multi-event competition contested in one day. A month later, he entered the GAA championship at Jones Road (now Croke Park) in Dublin and won an unprecedented seven individual crowns.

Kiely’s prolific run would continue for the better part of two decades, as he amassed over 1,000 medals, trophies and prizes. Although governed as an amateur sport, athletics took centre stage as the country’s premier spectator sport, aided in part by gambling to increase its popularity. Additionally, prizes awarded to the athletes tended to be practical (and valuable), such as clocks, suits of clothes, teapots, silver bowls and other items that a farmer like Kiely could use. It’s worth noting that at the time Irish-born athletes held the majority of throwing and jumping world records during their turn-of-the-century ‘golden age’—and held a virtual stranglehold on the hammer-throw for nearly 50 years.

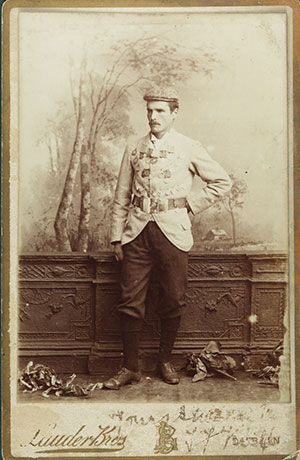

Above: A bemedalled Tom Kiely at the height of his sporting career in the 1890s. (Tipperary County Museum)

Kiely’s skills were not limited to the sporting arena. An article from the Waterford News and Star in 1895 reported:

‘He can take the floor and dance an Irish jig with a grace of expression that a professional might envy, and what is more can tune the fife to discourse most excellent music and has done so it may be said at many meetings where dancing competitions formed part of the programme’.

The Tipperary man’s striking good looks and tall, muscular build further augmented his larger-than-life persona. Poems were written in his honour and large crowds flocked to watch the famous sportsman. Kiely had little interest in celebrity or adulation, however, preferring instead the thrill of competition. In 1895 at Glasgow’s Celtic Park, the first dual meeting between Ireland and Scotland produced yet another layer to his towering legend. As he dressed in his tent after finishing his scheduled events, Irish officials hurriedly scrambled to find a last-minute replacement in the long-jump—the final contest to determine the meeting winner. Their man would be given only one attempt—and that’s all he needed. Without even lacing his shoes, Kiely sprinted down the runway and took flight, smashing the Scottish record and propelling his country to victory.

The following year saw the revival of the quadrennial Olympic Games in Athens, a competition deemed far less important at the time than the spectacle it would later become. It had little interest for Kiely and other premier athletes; the British Isles and America provided the most prestigious arenas of the day and the stiffest competition. Moreover, Kiely had no interest whatsoever in representing any country other than Ireland, despite being under British rule. In the summer of 1904, however, the allure of a combined Olympics and world championship in St Louis proved irresistible.

He set sail for New York on the steamship RMS Teutonic (built in Belfast by Harland and Wolff), paying his own way to maintain affiliation of his own choosing. The New York Times ran a headline on 3 June declaring, ‘IRELAND’S CHAMPION THOMAS KIELY HERE TO COMPETE IN OLYMPIC GAMES’. The all-around took place on 4 July (America’s Independence Day) during a torrential downpour. In the rain-soaked field the Tipp man was right at home. The ten disciplines comprised the 100-yards, shot-put, high-jump, 880-yard walk, hammer, pole-vault, 120-yard high hurdles, 56lb-weight throw, long-jump and mile run. Wearing a shamrock on his jersey, Kiely slogged through the mud and easily dispatched his rivals to win the gold medal.

For the next three months he enjoyed an extended victory tour in the US, where Irish-Americans fêted one of their own with a series of gala celebrations. The conquering hero finally returned to Ireland on 7 October at Queenstown (now Cobh); he was mobbed by large crowds and hailed by the GAA as a ‘living embodiment of our Gaelic manhood’. Kiely returned to the US in 1906 to claim another all-around world title, winning by an even bigger margin on a much dryer track in Boston.

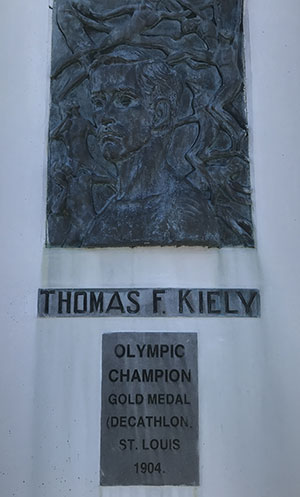

Above: The bronze memorial at Ballyneale, Co. Tipperary.

Over the years, much debate has centred round whether his 1904 St Louis victory had been officially part of the Olympics because it had occurred two months before the start of the other sports. The athlete himself was unconcerned. In a postcard to his family afterwards he wrote, ‘Well, I won the world championship’. An Olympic title back then would have been considered a lesser achievement in nearly all sporting circles and merely added another feather to Kiely’s well-adorned cap.

After retiring from athletics in 1908, he settled down with his wife on a farm at Fruitdale, near Dungarvan, where they raised eight children. He remained involved in sport as a mentor to young athletes before passing away in 1951. Remarkably, his personal bests remain competitive in the 21st century. His record in the triple jump would have ranked him third-best in Ireland last year, and he would have earned a top-ten placement in the long-jump, hammer and shot-put.

Today his namesake, Tom F. Kiely, a spry 83-year-old Clonmel resident, regales visitors with stories—and corrects the legion of apocryphal tales as well—about his famous grandfather. He confirmed the often-told accounts regarding his loyalty to country: ‘Grandfather took a green Fenian flag with the gold harp and planted it wherever he went to compete’. In his book Gold, silver and green, Kevin McCarthy adds: ‘Indeed, given the flux and state of torpor that Irish politics found itself in during these last years of Tory rule, it is not unrealistic to argue that he was a national hero in ways beyond the sporting field too’. A bronze memorial to ‘the Champion Kiely’ can be found outside St Mary’s Church and cemetery in Ballyneale, Co. Tipperary.

Christopher Warner is an Irish-American writer and actor, and has written extensively on sports history.

FURTHER READING

T. Hunt, Little book of Irish athletics (Stroud, 2017).

Kevin McCarthy, Gold, silver and green (Cork, 2010).

F. Zarnowski, All-around men (Lanham, 2005).