Sexual violence and the Irish Revolution: an inconvenient truth?

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2019), Volume 27The Irish Civil War is universally described as a war of ‘brother against brother’, but such a gender-exclusive metaphor cannot represent the particular violence that women experienced and which is a feature of all known wars.

By Linda Connolly

Rarely is the Irish Civil War described as a case of ‘brother against sister’ or vice versa. Moreover, a revisionist-style presumption that women in Ireland suffered less brutality than men has taken hold. Influential texts have therefore defined the violence of the Irish Civil War and War of Independence as gendered by focusing primarily on men’s experience, or have presumed that because these conflicts are considered ‘low rape’ wars there is little to address in the arena of sexual assault in particular.

Above: Black and Tans forcibly cut the hair of Sinéad (Orla Fitzgerald) in a scene from The Wind that Shakes the Barley. Forced hair-cutting was a common form of punishment for women during the Irish Revolution. (Joss Barratt/Sixteen Films)

Women in Ireland were in fact profoundly affected by the violence of both the War of Independence and the Civil War, despite being killed in relatively small numbers. Forced hair-cutting, frightening night raids in homes, beatings, verbal abuse, sexual harassment, invasive body-searching, destruction of homes, humiliating practices (such as stripping women in front of men) and psychological trauma caused by witnessing violence inflicted on others (including loved ones) were prevalent in areas of the country where violence was intense. Sexual policing of women, associated coercion and assaults were perpetrated by all sides and are widely reported in key sources (including the Bureau of Military History witness statements). Women’s bodies and sexuality were targeted in numerous ways. Seamus Babington from Carrick-on-Suir recalled one such assault in his witness statement:

‘… a rather wild sort of young woman, a native of Kilsheelan parish, was employed in Turner’s chemist shop and, like many other girls had a grádh for men in uniform. She ignored warnings and most dangerous at the time, used visit the barrack after the shops closed and then proceed home. This had to be stopped so two Volunteers from the Kilsheelan end of the town were ordered to be on the road … If they had exercised full intelligence they should have done nothing that night, after being seen. However, they carried out the order and, without over-description, gave the lady a thorough searching from head to foot without missing any of her inside garments. It was so thorough and minute that she did not dare call on the barrack again, but lost no time in reporting.’

Maggie Doherty

Above: Minister for Defence and head of the army Richard Mulcahy—directed that a court martial should be held in relation to the gang rape of Maggie Doherty by National Army soldiers, who were subsequently acquitted.

Evidence of different types of sexual violence, including gang rapes during the Civil War, arises in cases where women were publicly named and had their anonymity waived. One of the most horrific cases of sexual assault documented in the Military Service Pensions Collection (published on-line in 2018) is that of Margaret Doherty of Curanarra, Foxford, Co. Mayo. Margaret (known as Maggie) was born in 1896 and is listed in the 1911 census as aged fifteen and a scholar. In 1911 her father, Martin (a farmer), was 62 and her mother, Catherine, was 60. Margaret is the only daughter listed amongst seven sons. Three of the Doherty sons later joined the British and American armies; one of them was killed in Flanders.

Maggie Doherty’s military history and biography were very different to those of her three brothers who fought in World War I. In 1933 Mrs Catherine Doherty made a written application for a pension based on the loss of her daughter Maggie. The file details Maggie’s republican activism in Cumann na mBan from 1920 to 1923 but also refers to subsequent ill health from 1923 on. Because Catherine was paralysed on one side of her body, she was wholly dependent on Maggie and is described in the application as an invalid, unable to do anything.

At about 2am on the night of 31 May 1923, according to a letter submitted by her mother, Maggie ‘… was dragged from her bed and stripped naked and raped’. Her hands were tied, she was held at gunpoint and then ‘outraged’ (raped) by three men in succession. Prior to that night ‘… she was in perfect health and had never been ill. After that date she gradually failed, physically and mentally … She was totally incapacitated from 31/5/23 until death.’ Maggie never recovered from the psychological and physical injuries inflicted, and was institutionalised before she died prematurely, a young woman. The written medical evidence of three doctors who treated Maggie reveals that she ‘suffered from insomnia and depression’. One of the doctors wrote: ‘From her history, it is my opinion, her trouble was due to hellishly barbaric treatment at the hands of the Free State soldiers in 1923’. Maggie died on 28 December 1928 ‘in the mental hospital’ in Castlebar. She had stopped eating and had also developed tuberculosis-like symptoms.

The decision to grant a pension was dated 25 November 1936. Catherine received a partial dependant’s gratuity of £112 10s. in 1937, four years after her initial application, under the Army Pensions Act in respect of her daughter, referred to as ‘Cumann na mBan Intelligence Officer, Margaret Doherty’. Catherine died soon after, on 30 April 1938. The action of Catherine Doherty and her family in pursuing a pension inscribed in the State’s public archive a very explicit account of what happened to her only daughter. This has served to preserve Maggie’s personal story as well as a very uncomfortable aspect of National Army violence in 1923. The Dohertys’ pension application reveals that certainly between 1933 and 1937 the gang rape of Margaret was not concealed or covered up by her family or wider community. Letters of support were provided by the local headmaster, Church of Ireland rector and parish priest. Furthermore, according to a letter signed by Maggie’s brother (Patrick), dated 16 September 1935, a sworn inquiry by ‘Officers of the Free State Army’ was held into the attack. The family was obviously aware that the National Army took steps to investigate the atrocity but no further details were provided.

Court martial

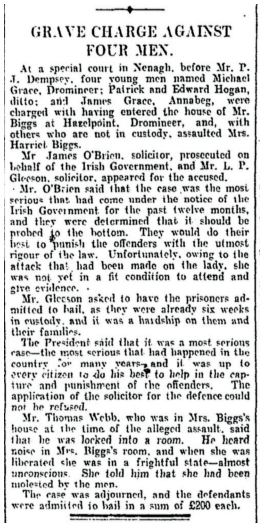

Above: The attack on Eileen Biggs was so prominent that it was publicly documented in the newspapers at the time, such as this report in the Irish Times, 9 August 1922, and referred to by Churchill in the House of Commons.

The late David Fitzpatrick has correctly observed in relation to the practice of terror that ‘Historians’ … primary function is to explain what occurred by assessing events from the perspectives of victim, perpetrator and onlooker alike’. Yet analysis of wartime sexual crimes often focuses on female victims and neglects the researching of perpetrators and any quest for prosecutions, justice or redress. Such evidence does exist. An Army Inquiry Committee was announced in the Dáil on 12 March 1924 in response to a potential mutiny by the National Army. It is apparent that the rape and assault of women was a core concern within the army leadership and Executive, led by W.T. Cosgrave. Critical records referring to a court martial held in Claremorris after the attack on Maggie Doherty are included in an Army Inquiry Committee (1924) report in the Mulcahy papers, held in the UCD Archives. Specific details regarding this case are included in the statement of Major-General Cahir Davitt, judge advocate general. Three perpetrators of the assault were named in the statement and it is clear that the Minister for Defence and head of the army Richard Mulcahy directed that a court martial should be held. The question of whether enough evidence existed to justify a conviction was doubted from the outset:

‘In the statement submitted to the Commission by the Minister for Home Affairs, mention is made of the case of LIEUTENANTS WATTERS, BENSON, and MULHOLLAND who were tried by General Court Martial at CLAREMORRIS on the 22/7/’23 for rape. I have available my files dealing with this matter.

- An abstract of the evidence available at the time, in this case was submitted me by the A.A.G. (2) with a request to be informed whether the evidence then available was sufficient to justify a conviction.

- COLONEL McCarthy of my staff replied on my behalf on the 3/7/23 in the negative.

- On the 7/7/’23 the Adjunct General wrote the Minister submitting the file for a direction.

- On the 10/7/’23 the Minister replied directing a Court Martial.’

The file states that it was considered advisable to invite the local civic guard and the parish priest of Foxford who reported the attack, Canon Henry Forde, to the trial, even though an acquittal was the presumed outcome before it even began. The government and the army were explicitly concerned to block any public commentary that might suggest that the court martial was not a serious attempt to secure justice. Protecting the reputation and public image of the army by being seen to hold a ‘trial’ was the stated priority. As predicted, ‘On the 23/7/’23 the officers were tried and acquitted. CANON FORD was in attendance.’ The trial was widely known about in the town, yet the chief superintendent in Castlebar, O’Hara, and the local inspector in Claremorris did not even attend, and speculation as to whether this was their choice, the result of an order or due to a lack of adequate communication on the date of the inquiry ensued:

‘COMMANDANT WALL who was the Command Legal Officer at CLAREMORRIS at the time states that the Civic Guard at CLAREMORRIS could not but be aware of the date and place of trial some time previous to the trial, as the same was general knowledge in the town of CLAREMORRIS. He never got any communication whatever from the Civil Guard with reference to the case.’

The actual proceedings of the court martial have not been publicly released to date and remain closed in the Military Archives, Dublin. The release of this file would enable a more in-depth understanding of this important case. The Army Inquiry file also outlines in detail how another horrific attack in June 1922 on two sisters (Flossie and Jessie McCarthy) in Kenmare, Co. Kerry, by members of the National Army was deliberated on extensively by the Executive, the attorney general and the army, and ultimately was covered up.

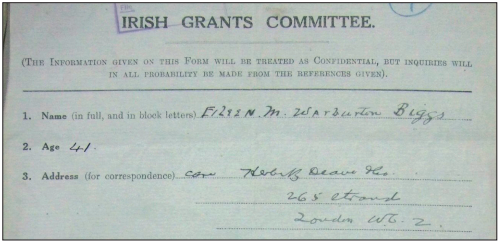

Eileen Mary Warburton Biggs

Another documented attack, which began around 9pm on 16 June 1922, involved the horrific gang rape of a Protestant woman near Dromineer, Co. Tipperary, by local anti-Treaty IRA men. Eileen Mary Warburton Robinson was born in Dublin in 1879. Her father, Robert Henry Robinson, was an army surgeon who had served in the Boer War. In the 1911 census Eileen is listed at her sister Grace’s marital home, ‘Bellevue’, Borrisokane, Co. Tipperary. Grace Mary Robinson (born in ‘S Africa’) was married to George Washington Biggs, of a landed military family. Eileen married George’s brother, Samuel Dickson Biggs, in 1918 at Kilbarron Church, Borrisokane, when she was 33.

In an Irish Grants Committee compensation claim application dated 2 December 1926, Eileen stated:

‘… several men came to the house. The men were in IRA uniform. They ransacked the house. Two men came into the room where I was, threw me on the bed and criminally assaulted me. Other men came in from time to time and did the same thing.’

Above: The Irish Grants Committee claim of Elizabeth Mary Warburton Biggs, who was awarded the notably large sum of £6,000.

Eileen was reportedly ‘outraged’ eight or nine times and was found in a state of collapse. She subsequently went to England with her husband and was awarded a notably large sum of over £6,000 in compensation. Eileen Biggs suffered life-altering physical injury and a mental breakdown after the attack. Her husband also had a nervous breakdown and suffered ill health until he died in Monkstown Hospital in 1937. The shame that resulted from the assaults perpetrated was palpable: ‘We cannot hold up our heads amongst friends and acquaintances’. This attack had a devastating impact on Eileen Biggs and her family. Eileen, Samuel, her sister Hilda and her mother Elizabeth Joyce Robinson had an address in Longford Place, Monkstown, Co. Dublin, by the 1930s. Like Maggie Doherty and other women who suffered trauma in the Civil War, Eileen died in a psychiatric hospital, St Patrick’s in Dublin, in 1950. She is buried in Mount Jerome cemetery with her sister, Grace Mary Biggs, in an unmarked grave. Neither was buried with their husbands in the Biggs plot in Kilbarron graveyard, Borrisokane.

The Biggses and Robinsons were military families, with members of both having served as officers in the Boer War and the First World War. Eileen’s brother, Major Robert Harvey St Clair Robinson, served in the 1916 Easter Rising with the 5th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, which took a prominent part in the battle of Cork Hill. He subsequently sat as a waiting member of the general court martial of Eoin MacNeill and others in May 1916. Whether this was known locally in Dromineer or was a possible motive in the attack on Eileen is unclear. Historians have documented local hostilities towards Protestants in the area more generally in this period. This attack was so prominent that it was publicly documented in the newspapers at the time and was referred to by Churchill in the House of Commons. Named perpetrators appear in a number of sources, including in the Irish Times on 9 August 1922:

‘At a special court in Nenagh before P.J. Dempsey, Dromineer: Patrick and Edward Hogan, ditto; and James Grace, Annabeg, were charged with having entered the house of Mr Biggs … and with others who are not in custody assaulted Mrs Harriet [i.e. Eileen] Biggs. Mr James O’Brien, solicitor, prosecuted on behalf of the Irish government.’

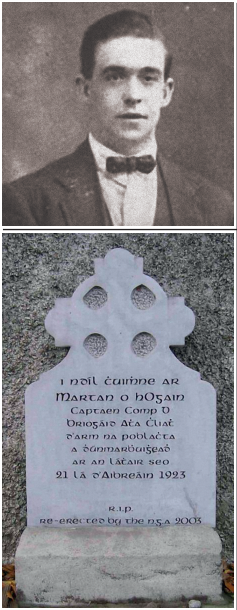

Captain Martin Hogan

Top: Captain Martin Hogan, leader of the Volunteers charged with the gang rape of Eileen Biggs in June 1922, who fled before the trial, and his memorial (above) on Grace Park Road, Dublin, re-erected in 2003.

The leader of the gang reported to have committed this atrocity, Captain Martin Hogan, brother of the Patrick and Edward who were charged, all Volunteers of the 1st Tipperary Brigade, had already fled. Similar to the Doherty case, those arrested and tried had impunity and were released. Hogan was subsequently engaged in military operations in Dublin city. On the evening of 21 April 1923, he was reportedly picked up by a Free State group operating out of Oriel House. His bullet-riddled body was discovered in a ditch at Drumcondra the following morning. It is believed that he was tortured before he was killed, aged 28.

The re-erection of two monuments honouring Captain Martin Hogan on Grace Park Road in Dublin, where he was shot, and off Banba Square, Nenagh, by the National Graves Association in 2003 has received no publicity or comment from Civil War historians despite his association with such a controversial gang rape. The separation of a documented gang rape from heroic remembrance raises very provocative questions in a moment of national commemoration from the perspective of both acknowledging transgressive sexual violence in the Irish Revolution and respecting the memory of female victims of the Civil War. Martin Hogan’s revolutionary story is also currently documented on an Irish schools’ website: https://www.scoilnet.ie/threads/stories/story/4/page/3. ‘Threads’ is an on-line initiative that provides a space for schools to store and share their students’ oral history projects. Sexual crime, however, is not mentioned as a topic requiring further analysis in the case-study.

Other such attacks in this period include the rape of Mary M., revealed by Lindsey Earner-Byrne, and the gang rape of the publican Mrs McGuill by three members of the B-Specials in Altnaveigh on 14 June 1922, which Robert Lynch has described:

‘A doctor who later examined her in Newry claimed that he had never seen so many bruises and cuts on one body before. She also had a fractured skull from repeated kicks in the head by her attackers.’

The role of gender-based violence, including cases of horrific rape perpetrated by offenders on both the pro- and anti-Treaty sides, is a largely unexplored aspect of the history and politics of the Irish Civil War and its aftermath. Perpetrators were not brought to justice and the attitude of the State to these cases requires further scrutiny. The stories of women who experienced the violence of the Civil War as sexual violence cannot be avoided either in the domain of ethical remembrance or in studies that seek to fully understand all of the violence that cast a shadow over the birth of the Irish state.

Linda Connolly is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Maynooth University Social Sciences Institute.

FURTHER READING

L. Connolly, Towards a further understanding of the violence experienced by women in the Irish revolution (MUSSI Working Paper Series, no. 7): http://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/10416/(2019).

L. Earner-Byrne, ‘The rape of Mary M.: a microhistory of sexual violence and moral redemption in 1920s Ireland’, Journal of the History of Sexuality 24 (1) (2015).

S. Hogan, The Black and Tans in North Tipperary: policing, revolution and war 1913–1922(Dublin, 2013).

R. Lynch, ‘Explaining the Altnaveigh Massacre, June 1922’, Eire-Ireland 45 (3–4) (2010).