‘Keeper of the flame’

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2019), Volume 27Brian O’Higgins and the Wolfe Tone Annual, 1932–62.

By Patrick Maume

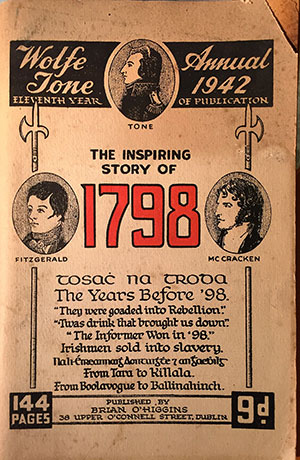

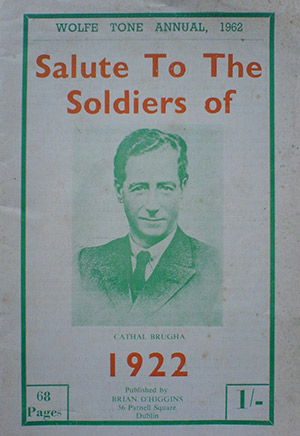

The Wolfe Tone Annual was published and largely written by the balladeer, postcard manufacturer and die-hard republican Brian O’Higgins (1882–1963) between 1932 and 1962, with illustrations by his business partners. O’Higgins used the Annual to comment overtly and covertly on recent history and current affairs to an audience extending well beyond his die-hard republican milieu.

Background

Brian O’Higgins was born in 1882, the youngest of fourteen children of small farmers at Kilskyre, Co. Meath. They claimed descent from a poor scholar wounded at the Battle of Tara in 1798. O’Higgins’s father was an IRB member, and O’Higgins recalled his grandmother describing Famine clearances and recalling many evicted individuals. O’Higgins was shaped by his family’s frugal Catholic piety and committed separatism; although anti-socialist, he equated republicanism with an egalitarian society of small farms and small businesses.

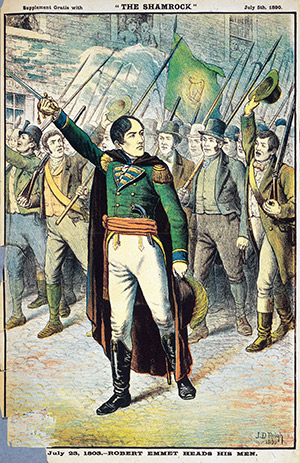

O’Higgins’s childhood reading was dominated by Young Ireland-influenced texts such as the Sullivan brothers’ Speeches from the dock and Irish penny readings, and the nationalist story papers The Shamrock and The Emerald. T.D. Sullivan’s satirical verse on current events (including the Land League agitation of the 1880s), as well as his more conventional heroic ballads, became O’Higgins’s poetic model. O’Higgins embraced John Mitchel’s angry resentment at the exploitation and humiliation of Ireland and his view of Ireland frozen in British malevolence until the Irish could break free through one supreme act of willpower.

O’Higgins’s combination of intense devotional piety and contempt for middle-class ‘Catholic Whig’ professionals and ‘Castle bishops’—political targets of the Parnellism of the early 1880s—was reinforced by the Parnell split.

Gaelic League milieu

After basic education at a national school, O’Higgins was apprenticed to a draper while writing for local newspapers. In 1901 he moved to Dublin and worked as a barman while entering the Gaelic League milieu. He went to Navan but returned to Dublin after clerical denunciations of Irish Ireland activists.

O’Higgins became a poorly paid professional Gaelic League speaker and organiser, a versifier (usually as Brian na Banban’) and stage entertainer at Gaelic League events, as a parody-shoneen lamenting the Gaelicisation of ‘Rawthmines’. In 1908 he married Teresa Kenny. Two of their seven children died in infancy and three entered religious life, while another was the Abbey actor and leftist Brian O’Higgins.

O’Higgins was active in the Irish Volunteers, and on the outbreak of war published the ballad ‘Who is Ireland’s Enemy?’, a list of English crimes ending with a call for revenge. He contributed verses to the commemorative brochure for O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral in 1915. He was in the GPO during Easter Week, and published The soldier’s story of Easter Week (1917). He represented West Clare in the First Dáil, helped to establish the local Sinn Féin courts system and then worked as a propagandist in Dublin.

Anti-Treaty

O’Higgins opposed the Treaty and was interned during the Civil War. His later denunciations of nineteenth-century clerical condemnation of nationalist revolutionaries, and of history as recounted by anti-national newspapers, reflect the Civil War era. In 1923 he was re-elected on de Valera’s surplus; he was defeated in June 1927 after siding with Sinn Féin. He was one of seven former TDs who in 1938 purported to transfer governmental authority to the IRA Army Council.

In 1924 O’Higgins founded a business with the artist Michael O’Brien, selling postcards, prayer-books, calendars and similar printed objects; O’Higgins supplied the text while O’Brien prepared illustrations, often brightly coloured stylised Celtic designs. O’Brien designed and illustrated the Wolfe Tone Annual until the mid-1950s, when he was replaced by Ailbhe Ó Monacháin.

O’Higgins was unimpressed by de Valera’s 1932–48 governments. In 1937 he established the Wolfe Tone Weekly to replace the recently suppressed An Phoblacht; the Weekly was suppressed in September 1939. During the war O’Higgins wrote to the papers (usually as ‘Brian Ó hUiginn’) expressing his views as far as censorship allowed. (On one occasion the censor published his letter with the name of de Valera—whom O’Higgins elsewhere called ‘His Majesty’s Prime Minister’—prefixed with ‘An Taoiseach’.) He regarded Garda detectives killed by the IRA as indistinguishable from Major Sirr, and celebrated the executed IRA chief-of-staff Charlie Kerins in a ballad. His autobiographical reminiscences written in the late 1940s claimed that Ireland was more Anglicised and less free than when he was young.

The 1944 Wolfe Tone Annual, which complained that the government’s economic mismanagement led to thousands of citizens emigrating to assist the war effort of ‘Ireland’s only enemy’, was suppressed by the censor. (O’Higgins republished it in 1945.) The suppression was raised in the Dáil by Denis Larkin. Seán McEntee insinuated (to O’Higgins’s indignation) that the question reflected a republican-communist conspiracy.

The Wolfe Tone Annual first appeared in 1932, raising funds for Tone commemorations; each issue dealt with an episode or individual in nationalist history. It marks O’Higgins’s realisation that his generation had been defeated, and his desire to transmit his version of recent history to prevent the next generation from being led astray by de Valera or rival nationalisms (usually Catholic-oriented) that disowned the republican tradition. It was a highly personal publication—O’Higgins sometimes confesses that he has overrun his allotted space and mentions topics that he had meant to address.

Ireland trapped in an eternal present

O’Higgins saw Ireland trapped in an eternal present in which the separatism of previous generations remained permanently valid. He followed Mitchel’s invocation of 1798, Griffith’s equation of himself with Mitchel and Redmond with O’Connell, and Pearse’s last pamphlets on the allegedly unchanging separatist tradition, quoted extensively in successive Annuals. Lord Edward Fitzgerald was ‘Commander-in-Chief of the IRA’ and Robert Emmet’s followers were ‘the IRA’. (The title was first used by the Fenians.) O’Higgins quoted Tone’s description of Newgate prison filled with United Irishmen before remarking:

‘Now that we have copied these words from a letter written by Wolfe Tone 155 years ago, the fear seizes us that some of the disaffected among our readers may alter “Newgate” to “Portlaoighise” and “United Irishmen” to something else, and attempt to apply them to the position and the prospects of Ireland in these our own delightful days.’

(Wolfe Tone Annual (1948), p. 92)

O’Higgins adopted Mitchel’s devil theory—that British oppression of Ireland over the centuries was simply a monolithic, ruthless, conscious and continuous conspiracy to exterminate the native Irish. He saw himself fighting an ‘English lie’ going back to Giraldus Cambrensis. Any Irish writer who disagreed with his definition of Irish nationality must be in conscious or unconscious bad faith and deserved no mercy. The historical figure to whom O’Higgins displayed the deepest hostility was Daniel O’Connell—‘Liberator of placehunters and Castle Cawtholics’. O’Higgins reiterated the republican claim that Catholic Emancipation merely created a class of ‘Catholic Whig’ job-hunters whose ability to manipulate the Catholic hierarchy would have damaged the faith of the Catholic people but for individual holy patriot priests. He was outraged by suggestions that O’Connell could not be blamed for not anticipating twentieth-century republicanism:

‘The silly statement has been made … that the Republic declared in 1916 had no connection whatever with ’98, ’48 or ’67 … and was fashioned on the American model; but any schoolboy who has read Irish history intelligently can give that statement the lie … the unbroken tradition has come down to us from unconquered Ireland of the long centuries since first our fathers gave resistance to the English invader.’

O’Higgins’s opponents here were contributors to the Catholic weekly Standard who advocated specifically Catholic nationalism and suggested that nineteenth-century clerics who criticised separatist links to Continental secret societies might have had some justification.

Any attempt by Irish nationalists to ally with elements in British society represented only humiliating subservience. Thomas Moore was excoriated for trying to arouse British pity for the defeated Irish, in contrast to the manly defiance of Young Ireland verse. W.B. Yeats was equated with Moore.

Intelligent criticism

O’Higgins’s criticisms of individual historical writers are often intelligent. His separatism made him conscious of the influence of liberal apologetic on memoirs and histories of Irish rebellion—for example, the contrast between Edward Hay’s claim that there was no United Irish organisation in Wexford in 1798 and Myles Byrne’s demonstration that there was. He criticised depictions of Ann Devlin and the women of Young Ireland as lovelorn maidens rather than committed activists. He showed extensive knowledge of Irish historical literature, and rarely seemed to engage in conscious falsification (an exception being his reference to Sarah Curran’s marriage without mentioning that her husband was a British officer), but he was ultimately a rationaliser and an authoritarian rather than a historian. To criticise Tone was, for him, to be complicit in Tone’s death. O’Higgins reiterated that Ireland would only be free when anyone who criticised national heroes, opposed compulsory Irish or the GAA ban on foreign sports, or supported partition was so severely punished that no one would dare to repeat the offence.

Holocaust denial

The writings of his favourites were not contextualised but treated as self-evident—Tone’s statement at his trial that he always opposed British rule was sufficient to disprove claims that he was an imperialist in his youth, and Mitchel’s claim that the Famine was produced by a British plot dating back to 1829 required no further proof. Similarly, O’Higgins’s legitimate criticism of evasions of the violent and catastrophic aspects of British rule in Ireland, coupled with his view that Britain was ‘Ireland’s only enemy’, led him to holocaust denial. In a Wolfe Tone Annual on the 1798 Rising, he wrote:

‘These [atrocities by Crown forces in 1798] were only some of the atrocities that came under the notice of an eyewitness; there were scores of others even more terrible, but they would scarcely be believed by the superior and enlightened people of our day who, since the conclusion of World War II, have been rushing from cinema to cinema in search of the atrocity films manufactured by certain “peace-loving nations” as part of their war of revenge on defeated peoples, their successful propaganda for the blackening of their enemies and the spread of the idea that they themselves would never, under any circumstances, be guilty of brutality or inhumanity. One not used to their ways, in peace and in war, would imagine there had never been Black and Tans in Ireland, nor Yeomen, nor Hessians, nor crowbar brigades, nor poorhouses, nor pitchcaps, nor gibbets, nor midnight burnings, nor planned famine, nor enforced exile, nor defamation of the dead, nor any of the barbarities that have at all times accompanied the campaign of conquest of the English invaders here in Ireland. If the horrified cinema “fans” would stay at home for a while and read the history of British rule in Ireland it might make them a little less credulous when the silver screen presents to them the savagery and inhumanity and brutality of all who have been or are at war with peace-loving, Christian, chivalrous honourable England … [O’Higgins goes on to describe the burning alive of rebel patients in a hospital in Enniscorthy and a loyalist historian’s “excuse” that it accidentally caught fire while the patients were being shot] … If the like had been depicted as having taken place at Belsen or some other “torture camp”, how our doped and unthinking cinema addicts would raise their eyes in horror.’

(Wolfe Tone Annual (1948), pp 94–5)

Advertisements

The Annual may well have been profitable; its advertisements note a scheme for sending gift copies as presents to friends overseas, and its lists of available back issues make it clear that the majority had sold out. It advertised such Irish-made products as Kennedy’s bread, Solus lightbulbs, Ancient Irish Vellum notepaper and Urney sweets. O’Higgins, however, did not see the enterprise primarily in financial terms; in 1959 he ceased publishing advertisements, since they were the most laborious aspect of the publication and old age made it difficult for him to carry on the work. The same Annual criticises Dr Philbin, bishop of Clonfert, for saying that the founder of a factory may be a patriot of equal merit with one who dies for the country; O’Higgins objected that the factory-owner was driven by self-interest, whereas the martyr sought no personal gain.

Brian O’Higgins died suddenly on 10 March 1963 at St Anthony’s Church, Clontarf, where he had been a daily attender. The Irish Independent published an obituary; the Irish Press did not, possibly because his criticisms of de Valera and Fianna Fáil cut too close to the bone. O’Higgins’s insistence on the undying relevance of Mitchel and Tone to mid-twentieth-century Ireland reflects a quest for social, personal and intellectual fulfilment as intense, if less sophisticated, than that of his contemporaries explored by Roy Foster in Vivid faces, a genuine anger at the injustices of Irish society and a hatred shading into monomania.

Patrick Maume is an editorial assistant with the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

FURTHER READING

P. Maume, ‘O’Higgins, Brian (1882–1963)’, in Dictionary of Irish Biography.

B. O’Higgins, Wolfe Tone Annual (1950): ‘1916, Before and After’.

B. O’Higgins, The soldier’s story of Easter Week (ed. C. O’Higgins) (Dublin, 1966).

P. Ó Tuile, Life and times of Brian O’Higgins (Navan, 1965).