Viscount Hugh Gough—an ‘illustrious Irishman’ and controversial British military commander

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2018), Volume 26The National Library of Ireland recently catalogued and made available the Gough papers, a collection relating to Hugh Gough and his family. The papers reveal much about the life of this ‘illustrious Irishman’ and his lengthy military career.

By Fionnuala Walsh

Above: Beheaded in 1944, blown up in 1957 and finally exiled from Ireland in 1986, the equestrian statue of Viscount Hugh Gough now stands in Chillingham Castle, Northumberland. (John Byrne)

Peninsular War

Hugh Gough was born in Limerick in 1779, the fourth son of a military officer. He joined the army at the age of thirteen and served at the Cape of Good Hope and the West Indies soon after. He married Frances Stephens in 1807. Their close relationship is evident in the many affectionate letters between the couple in the collection. For example, during the Peninsular War Gough wrote very regular letters to Frances, which describe in great detail his experiences in the military and give insights into his personal character. He was most disappointed that she could not join him in Spain in 1810. He also wrote of his conflict over the urge to seek honour and glory in the army versus his desire to be home with his wife and children. Their first child, a son, died at two years of age while Gough was serving overseas in 1813. A daughter, Letitia, followed in 1815 and eventually four more children.

Gough was seriously wounded twice in the Peninsular War and applied for a medical pension in 1815, citing his injuries. He spent the next few years on half-pay, but it is evident from his correspondence that financial worries were a significant concern for him and that, as a younger son, he felt obliged to work to earn a living. In 1819 Gough was given command of the 22nd Regiment of Foot, which was sent to Ireland in 1821. The regiment was based in Cork but was also active in Galway and Tipperary, where it played a role in suppressing the agrarian violence led by ‘Captain Rock’. The 22nd was sent to Jamaica in 1826 but Gough did not join it, unwilling to leave his young family. Instead, he leased Rathronan house and estate in Tipperary, where he and his family settled for the next eleven years. He served as a magistrate and immersed himself in the local community.

First Opium War

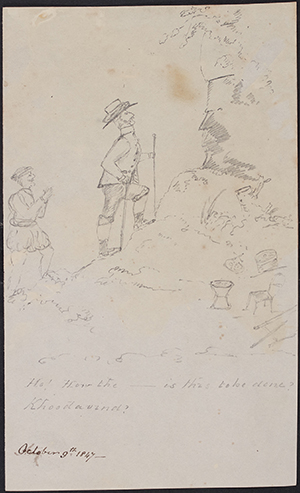

Above: A drawing of Gough in India by a family member, 9 October 1847. (NLI)

The Chinese papers in the Gough collection provide a rare insight into the Chinese perspective on the Opium War and the relationship between the British Army and the Chinese government. They include detailed correspondence between Hugh Gough and Karl Gützlaff, a German missionary to the Far East who served as an interpreter for the British diplomatic missions and acted as an essential intermediary between the British military and the Chinese population. The papers include Gützlaff’s translations of Chinese documents about the British military and government, as well as some documents in Chinese. It is interesting to read the Chinese perceptions of the British soldiers, describing them as ‘rebellious English foreigners’ and ‘barbarians’ and accusing them of rape and rapine.

Although Gough received praise and honours for his role in the Opium War, the war itself was the subject of some contemporary criticism. For example, William E. Gladstone denounced the war in parliament as ‘unjust and iniquitous’ for its promotion of the opium trade and argued that it would cover Britain with ‘permanent disgrace’. Hugh Gough himself addressed the question of the legality and morality of the war in a letter regarding prize money for the British soldiers. He was having difficulty securing the prize money to which he believed his troops were entitled owing to debate over whether the British government was in fact at war in China. Gough considered the issue to be quite simple. They were either at war, in which case the soldiers were entitled to prize money, or they weren’t, in which case he was a murderer: ‘if we were not at war with China, there is not a man in Europe more richly deserves hanging than myself. If we were at war I will fearlessly assert no army ever better merited every reward.’

Gough appears to have been less interested in diplomacy or the political ramifications of his actions than in military action itself. In India, he wrote in a letter home that the governor-general was anxious not to fall into the trap of ‘making war without ample cause for doing so’. He stated that such an attitude might be ‘all right politically, but it hampers me, so as to give perfect security to all points’.

Anglo-Sikh Wars

In 1843 Gough returned to India, where he was appointed commander-in-chief of the British Army and where he spent the next six years. He was in command during the Gwalior campaign in 1843 and the Anglo-Sikh Wars of 1845–6 and 1848–9, which were fought between the British East India Company and the Sikh Empire. The collection contains numerous documents, such as field returns, maps and plans of attacks relating to these wars, of particular value to those interested in military strategy and tactics. It also includes a number of despatch and letter books containing copies of hundreds of official letters between Gough and various correspondents, including the duke of Wellington, the earl of Ellenborough, Lord Fitzroy Somerset and Sir Frederick Currie, resident at Lahore. Initially Gough’s success in the Anglo-Sikh Wars earned him praise and accolades such as the ‘saviour of British India’, while the Battle of Subraon in 1846 was described as the ‘Waterloo of India’. He himself wrote in glowing terms to his son George of their victory in December 1845 as ‘glorious’ and the hardest-fought action that ever took place in India. He believed that he was doing God’s work and cared little for criticism at home for the losses sustained: ‘the fearful losses will in their estimation be laid to my rashness, but whatever they may say believe this one fact, that but for that apparent rashness India was lost’ (16 January 1846). He wrote of the difficult position in which he found himself in India: ‘It is rather hard my actions in China were not accounted of any moment because they were effected without much, indeed very little loss. In India I am a reckless savage devoid of stratagem and military knowledge because my loss is severe.’ He was confident of his decisions: ‘Posterity will do me justice and the stoutest of my maligners may yet learn that my confidence in my army went far to serve India’.

In 1843 Gough returned to India, where he was appointed commander-in-chief of the British Army and where he spent the next six years. He was in command during the Gwalior campaign in 1843 and the Anglo-Sikh Wars of 1845–6 and 1848–9, which were fought between the British East India Company and the Sikh Empire. The collection contains numerous documents, such as field returns, maps and plans of attacks relating to these wars, of particular value to those interested in military strategy and tactics. It also includes a number of despatch and letter books containing copies of hundreds of official letters between Gough and various correspondents, including the duke of Wellington, the earl of Ellenborough, Lord Fitzroy Somerset and Sir Frederick Currie, resident at Lahore. Initially Gough’s success in the Anglo-Sikh Wars earned him praise and accolades such as the ‘saviour of British India’, while the Battle of Subraon in 1846 was described as the ‘Waterloo of India’. He himself wrote in glowing terms to his son George of their victory in December 1845 as ‘glorious’ and the hardest-fought action that ever took place in India. He believed that he was doing God’s work and cared little for criticism at home for the losses sustained: ‘the fearful losses will in their estimation be laid to my rashness, but whatever they may say believe this one fact, that but for that apparent rashness India was lost’ (16 January 1846). He wrote of the difficult position in which he found himself in India: ‘It is rather hard my actions in China were not accounted of any moment because they were effected without much, indeed very little loss. In India I am a reckless savage devoid of stratagem and military knowledge because my loss is severe.’ He was confident of his decisions: ‘Posterity will do me justice and the stoutest of my maligners may yet learn that my confidence in my army went far to serve India’.

Above: Scenes from India during the Anglo-Sikh Wars, 1840s, possibly painted by Viscountess Gough. (NLI)

The victory at Goojerat ensured that Gough was made a viscount on his return to England and received a generous pension, as well as many other honours. He returned to live in Dublin, and died in 1869 at his home in St Helen’s, near Booterstown, Dublin.

Fionnuala Walsh is a Teaching Fellow in the School of History, University College Dublin.

Read More:

FURTHER READING

M. Barthorp, Queen Victoria’s commanders (Oxford, 2000).

D.G. Boyce, Nineteenth-century Ireland (Dublin, 2005).

R.S. Rait, The life and campaigns of Hugh, first Viscount Gough, Field-Marshal (London, 1903).