Under the hammer blow

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2018), Volume 26, World War IIrish units facing the 1918 German spring offensive.

By Mark Phelan

By early 1918, after more than three years of bloody stalemate, the strategic situation on the Western Front was delicately poised. While both sides suffered the effects of war-weariness, Germany in particular struggled against low morale, as a combination of poor harvests and British blockading created severe foodshortages at home, while America’s entry into the war on the side of the Entente in April 1917 had greatly improved the long-term prospects of an Allied military victory. Elsewhere, however, the Central Powers had achieved significant successes, with the result that Germany planned to strike hard and fast in France with the full onset of spring.

Entente crises

Above: From late 1916, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg (left) and his domineering assistant, General Eric von Ludendorff (right), became de facto military dictators of Germany. Pursuing outright victory, they unleashed an epic offensive in the spring of 1918, with Ludendorff assuming operational command.

Profound crises rocked the Entente in 1917. A disastrous French offensive towards theChemin des Dameshad been followed by widespread mutinies that almost knocked France out of the war. To shore up the French war effort, the British in turn ploughed hundreds of thousands of men into the inconclusive Battle of Passchendaele (31 July to 10 November 1917). Across the Alps, meanwhile, Italy, which had joined the Entente in 1915, suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Caporetto. For more than two years Italian conscripts had attacked Austria-Hungary along the narrow front of the River Isonzo lowlands. By October 1917 the Italians were exhausted and fell easy prey to a surprise counter-offensive spearheaded by élite German troops that included the future ‘Desert Fox’ Erwin Rommel. Aided by Anglo-French reinforcements and showing impressive resolve in their own right, the Italians ultimately halted the enemy advance at the gates of Venice, and eventually recaptured all of the lost territory in late 1918; but for the moment this theatre posed no threat to the Central Powers. Neither did the Eastern Front, where Romania, which had joined the Allies in 1916, was overwhelmed by German, Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian and Ottoman forces. Simultaneously, the Russian war effort fell to pieces. In February 1917, military and industrial strikes led to the overthrow of the Tsarist system, to be replaced by a western-orientated parliamentary regime. In truth, real power lay with councils of soldiers and workers (‘soviets’), who no longer identified with the war. This period ofDuovlastie(‘dual power’) witnessed the complete collapse of Russian military discipline, which in turn facilitated rapid German breakthroughs toward St Petersburg and the overthrow of the Provisional Government by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in October 1917. At this point Russia’s war became a civil one, although the Bolsheviks did not sign a formal peace with the Central Powers until March 1918. In the interim, the Germans consolidated their control of the former Tsarist borderlands, and transferred nearly 50 experienced divisions to France and Flanders.

British forces targeted

Thus the stage was set for Germany’s second great gamble in the west. Now ade factomilitary dictatorship, Germany expected her armies of 1918 to atone for the flawed 1914 invasion of France, which had been thwarted at the First Battle of the Marne. Although the German parliament called for a negotiated peace in August 1917, the Russian Revolution impelled the general staff to stake everything on a war-winning offensive. In its conception the 1918 campaign targeted the British rather than the French. According to the Germans’ calculations, victory against the French would have little impact on British belligerence. Even if France succumbed, argued Germany’s chief strategist, Gen. Eric Ludendorff, the British and their allies could hold out in the north pending the culmination of the ongoing American build-up. Conversely, Ludendorff expected that if Germany overran the channel ports, and thereby knocked the UK out of the war, France and America would both seek terms.

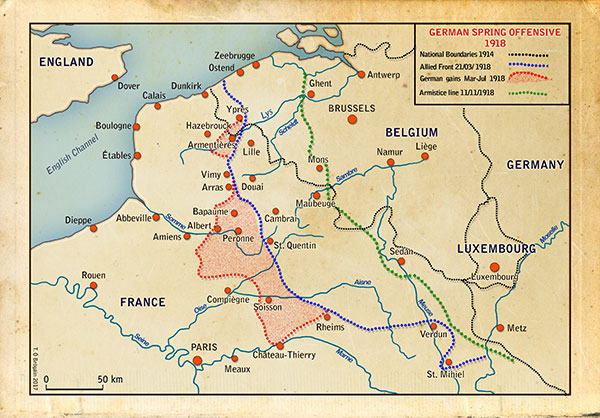

Although the British generals anticipated the main thrust of the German strategy, they wrongly expected the pending attack to follow a direct line from Ypres to Calais, Dunkirk and Boulogne. The Germans had a subtler plan in store. In short, Ludendorff authorised a series of linked offensives, with the first and largest blow (code-named ‘Michael’) falling upon the southernmost reaches of the British line. Intended to drive a wedge between the Anglo-French armies while drawing off the British reserves in Flanders, Operation Michael would set up a second strike (initially code-named ‘George’ but subsequently revised to ‘Georgette’) intended to roll up the British forces guarding the channel ports.

The initial blow of the spring offensive would fall upon a 70km front between Arras and La Fère. The ground here was firm in comparison to Flanders, and dried up faster in springtime; the Germans expected, therefore, to avoid the boggy conditions that had blighted the British drive on Passchendaele. Furthermore, the British had only just assumed responsibility for this front from the French, and in extending their lines southwards became dangerously stretched. Meanwhile, the discreet policies of Prime Minister David Lloyd George compounded the British manpower shortage in the crucial sector. Aghast at what he perceived to be the pointless expenditure of British lives in 1917, and intent upon forcing his generals onto the defensive pending full-scale American deployment, Lloyd George conspired to retain large numbers of conscripts in the UK and to divert others to the Palestine campaign.

Irish forces in the firing line

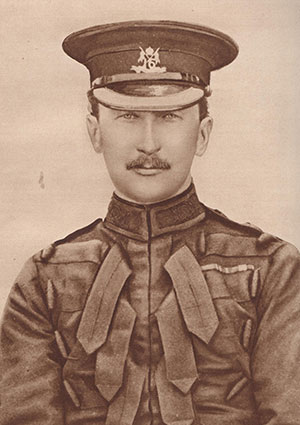

Above: Commander of the British Fifth Army General Hubert Gough. Cashiered for incompetence while the retreat was still underway, Gough was a high-profile Irish casualty of the subsequent analysis into the Fifth Army’s performance.

Consequently, the Germans enjoyed a seven-to-one manpower advantage in the pending combat zone, the larger part of which was manned by Gen. Hubert Gough’s battered Fifth Army. This force included the 16th(Irish) Division, with its core of nationalist volunteers, and the predominantly loyalist 36th(Ulster) Division, both of which lined up directly opposite the pending German steamroller. Assigned to the VII Corps, the 16th(Irish) Division defended a 6km front between Epéhy and Ronssoy. This sector guarded the southern flank of the Flesquières salient, a key target identified by the Operation Michael planners. Meanwhile, the Ulster Division joined the XVIII Corps, which guarded Saint-Quentin, an important rail junction and therefore also a priority objective of the Germans.

As spring approached, the Irish divisions remained constantly in the front line, where they worked desperately to implement a doctrine known as ‘elastic defence’. This involved three zones of operation. Each divisional front incorporated a forward, battle and rear zone. Theoretically, the forward zone consisted of supporting redoubts manned by a handful of companies, which would disrupt the German onslaught before falling back in good order upon the battle zone. Here, several kilometres behind the front line, the bulk of the defenders would be ready to repulse the suitably bloodied German assault troops, while reserves held back in the rear zone would deal with any breakthrough. In practice, the manning and preparation of the various zones was erratic and subject to the poor judgement of local leaders such as the head of the VII Corps, General Sir William Congreve. Backed by his consistently wasteful superior, Hubert Gough, Congreve insisted on concentrating the bulk of his battalions in the forward zone, thereby pursuing a strategy that ignored every hard lesson imparted by the battles of 1916–17, and which left the 16th(Irish) Division in particular facing an impossible task.

Poor visibility

The storm finally broke at 04.40hrs on 21 March 1918. Marking the high tide of artillery concentration during the First World War, c. 10,000 guns and trench mortars provided a crushing overture to the great attack. Although it lasted only five hours, the preliminary bombardment expended 1.16 million shells, compared to the 1.5 million fired by the British in an entire week before the 1916 Battle of the Somme. Weather conditions accentuated the impact of the shellfire, with a thick fog smothering the forward zone of the Fifth Army. Even without the artificial elements of smoke canisters and poison-gas rounds that featured heavily in the barrage, the natural fog greatly hampered exposed units such as the 16th(Irish) Division, which relied upon accurate machine-gun fire to protect the scattered outposts near the front line. When the German storm troops moved forward at mid-morning, they rapidly swamped Irish redoubts that had somehow survived the bombardment but could not support each other owing to poor visibility.

Despite these disadvantages, the 16th(Irish) Division fought fiercely on 21 March 1918. On the left side of the Irish front, the battalions of 48 Brigade (1/Dublin Fusiliers, 2/Dublin Fusiliers and 2/Munster Fusiliers) wrote another page in their illustrious histories by holding on east of Epèhy. While each of these units contended with overwhelming odds, the actions of the 2/Dublins, who sacrificed themselves at ‘Ridge Reserve’ trench, were particularly noteworthy, as they prevented flanking German stormtroops from enveloping 48 Brigade completely. The threat of encirclement occurred because 49 Brigade (2/Royal Irish Regiment, 7/Royal Irish Regiment and the composite 7/8Inniskilling Fusiliers) had been driven out of Ronssoy in short order. The German barrage caught and smashed the Royal Irish battalions, who nevertheless mounted a furious if hopeless defence of Lempire, a north-eastern extension of Ronssoy itself. Meanwhile, a flood of stormtroops crashed into Ronssoy from the nearby ‘Cologne Valley’ and swept away the amalgamated 7/8 Inniskillings.

As the forward zone cracked and crumbled, 47 Brigade (6/Connaught Rangers, 1/Munster Fusiliers, 2/Leinster Regiment) received orders to counter-attack. When it transpired that the battle zone had been lost, the divisional HQ cancelled the attack. This counter-order reached the Munsters and Leinsters but not the Connaught Rangers, who advanced in isolation and without artillery support in the direction of St Emilie. Tragedy followed, with the Rangers—most likely the only unit of the BEF to advance on 21 March 1918—fighting their way into the outskirts of Ronssoy Wood, where the Germans captured the hapless survivors when their ammunition expired. At nightfall, a handful of Rangers returned safely to the makeshift defences of the ‘Brown Line’, which was the scene of further brutal fighting on 22 March. Here the Rangers’ remnants linked up with the 1/Munsters, the 2/Leinsters and scratch details of engineers, signallers and military police, all of whom fought gallantly against overwhelming odds. In the event, however, breakthroughs elsewhere rendered the Brown Line position untenable, and so a general retreat, not fully halted until mid-April, began.

Ulster Division

Above: Portrait of Major-Gen. Oliver Nugent, GOC of the 36th Ulster Division for most of the war, by William Conor. Nugent wisely chose to locate a proportionate number of his battalions in the forward, battle and rear zones on his front, with the result that the Ulster Division was better deployed than the 16th (Irish) Division.(Belfast City Council)

Further south, the Ulster Division likewise suffered heavy losses on 21 March 1918. The Ulstermen held a 5km front along an east–west axis across the southern suburbs of Saint-Quentin, with the forward zone anchored on hilly terrain well suited to defence. Moreover, unlike Congreve of the VII Corps, the commander of the XVIII Corps, Gen. Sir Ivor Maxse, left his divisional commanders to their own devices when it came to battlefield deployment. Given latitude, the Ulster Division commander, Gen. Oliver Nugent, wisely chose to locate a proportionate number of his battalions in the forward, battle and rear zones on his front, with the result that the Ulster Division was better deployed than the 16th(Irish) Division. In theory, the Ulstermen also enjoyed solid protection from eastward-projecting flanking divisions, which meant that the Germans would need to achieve deep breakthroughs elsewhere before they could threaten the Ulster rear area. Unfortunately, because the main weight of the attack toward Saint-Quentin fell on a British division thathadopted for a risky forward concentration, this is precisely what happened.

On21 March, German stormtroops quickly infiltrated the Ulster forward zone. Taking advantage of the especially heavy fog at Saint-Quentin, they surrounded and bypassed the shrouded redoubts, most of which surrendered with little resistance. The heroic stand of ‘C’ Company, 12/Irish Rifles, stood out as a notable exception, with the doomed Belfast unit stoutly manning Foucard Trench until late afternoon. Elements of a sister unit, the 15/Irish Rifles, also showed immense courage at the strongpost known as Racecourse Redoubt. From Comber, Co. Down, the local commander at Racecourse Redoubt, Lt. Edmund de Wind, only received his commission into the Irish Rifles in 1917. As a pre-war emigrant to Toronto, de Wind had first enlisted as a private in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, wherein he saw extensive action at the Somme and in Flanders, which marked him out for the leadership role he played during the opening act of the Michael Offensive. ‘For seven hours’, noted his Victoria Cross citation, de Wind held his ground ‘and, though twice wounded and practically single-handed, he … continued to repel attack after attack until he was mortally wounded and collapsed’.

Having lost its three forward zone battalions (2/Inniskillings, 12/Irish Rifles, 15/Irish Rifles) on the first day, the 36th(Ulster) Division courted complete disaster on 22 March. Dangerously, Gen. Gough had issued confusing guidelines about the feasibility of withdrawing in certain exceptional circumstances. Misinterpreting these guidelines, Maxse ordered the XVIII Corps to fall back toward the Somme River, nearly 15km behind the battle zone. Consequently, his shattered corps had to break cover and retreat in broad daylight, with numerous English battalions being shot to pieces while executing this dubious manoeuvre. Maxse’s solorun also contributed to the destruction of the 16th(Irish) Division, for the Saint-Quentin withdrawal meant that the limited British reserves at Epèhy-Ronssoy had to shift south in order to avert a putative rout.

Fortunately, the rump Ulster Division survived the daylight retirement without incurring further heavy losses. The Ulster’s three reserve zone battalions (2/Irish Rifles, 9/Irish Fusiliers, 9/Inniskillings) had escaped the previous day’s onslaught with only minor losses, and were thus in good shape to fight a running rearguard. Another battalion, the 1/Inniskillings, suffered 50% casualties defending the battle zone on21 March, yet the survivors still played a critical role in covering the retreat, beating back relentless attacks by Prussian Guardsmen and thereby covering the crucial first stage of the divisional withdrawal to the Somme.

Suspicions of ‘political disaffection’

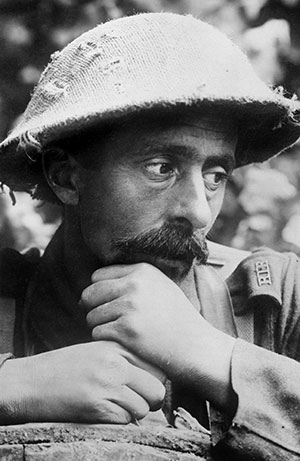

Above: A soldier of the Royal Irish Rifles taken prisoner by the Germans in March 1918. (IWM)

Cashiered for incompetence while the retreat was still under way, Gen. Gough was a high-profile Irish casualty of the subsequent analysis into the Fifth Army’s performance. In a different context, the 16th(Irish) Division also became something of a convenient scapegoat, with suspicious minds raising bugbears about ‘political disaffection’ and a concomitant poor fighting spirit on the part of the Irish rankandfile. The facts told a different story. In total, the 16th(Irish) Division lost nearly 3,000 men during the opening 48 hours of the Michael Offensive, while the Germans also took very few prisoners on the Irish front. This loss has to be understood in the context of the unit’s pre-battle strength of c. 5,400 rifles. In fighting so determinedly, the 16th(Irish) Division effectively sacrificed itself on behalf of the wider Fifth Army. Admiring German combat reports rightly acknowledged the role played by the Irish battalions. These accounts contrasted sharply with the tone of Field Marshal Douglas Haig’s wartime diary, which effectively slandered his ‘southern’ Irish troops.

The Ulster Division incurred a similar number of casualties, while hundreds more entered captivity as POWs. Unlike the 16thDivision, however, the Ulster losses did not include significant reputational damage. For this reason a rebuilt 36th(Ulster) Division retained its ethno-political identity until the war’s end. Conversely, the high command, pointing to the dearth of Irish volunteers, reduced the battalions of the 16th(Irish) Division to training cadre status, or otherwise struck them from the army list. Other options existed but went unexplored. By welding the limited Irish reserves to several Irish battalions withdrawn from Palestine in June 1918, it would have been possible to restore the 16th(Irish) Division in rough accordance with its original constitution. By now, however, the upper echelons of the military had no desire to play to Irish national sentiment, and so no steps were taken to retain a force heavily identified with the struggling Home Rule project.

Failure

The Michael Offensive shook the BEF to its core, but it did not split the Anglo-French armies, nor did it create the conditions for a German victory in Flanders. Even so, Ludendorff unleashed a follow-up offensive toward Amiens in April 1918, before switching south to the Aisne in May. In each instance the Germans scored spectacular early successes. These, though, came at an enormous cost, and the attacking divisions had insufficient logistical resources to exploit their initial gains. Steadily augmented by the American deployment, the French and British also belatedly mastered the art of defending in depth and sacrificed useless ground in order to curtail the Germans at a location of their own choosing. By midsummer, therefore, the German gamble of 1918 replicated the failure of 1914, with a great salient from Verdun to Ypres threatening Paris but with the Allies preparing to turn the tide on their exhausted enemy.

Mark Phelan lectures in history at NUI Galway.

FURTHER READING

- M. Laffan,The resurrection of Ireland: the Sinn Féin Party 1916–1923(Cambridge, 1999).

- D. Ó Corráin, ‘“A most public spirited and unselfish man”: the career and contribution of Colonel Maurice Moore, 1854–1939’,StudiaHibernica (2014).

- M. Wheatley,Nationalism and the Irish Party: provincial Ireland 1910–1916(Oxford, 2005).