Letting sleeping dogs lie

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2018), Volume 26James W. Upton’s unpublished silver jubilee history of the Gaelic Athletic Association.

By Tony Keating and Mark Reynolds

On 27 April 1932, the annual congress of the GAA approved a request by the association’s central council to advertise for expressions of interest from ‘suitable’ authors to write an official history of the GAA, to mark the association’s upcoming silver jubilee in 1934. An advertisement was placed in the Irish Press in July 1932, and in September the council selected the veteran republican and Gaelic games journalist James W. Upton as the author. Upton’s manuscript was never published, however, for reasons never accurately explained by the GAA or publicly commented on by Upton. Indeed, until recently Upton’s history was thought to have been lost, but the recent discovery of a surviving copy of his manuscript, combined with the thin trail of archival material, provides a fascinating insight into how the realpolitik of the day clashed with Upton’s journalistic ethics to ensure that the history was never published.

Above: James W. Upton (right) at Bodenstown c. 1920s with a close friend, Canon Hackett. Born in Waterford in 1872, Upton had a lifelong commitment to Gaelic games, republicanism and socialism. (Upton family)

James W. Upton was born in Waterford in 1872 and had a lifelong commitment to Gaelic games, republicanism and socialism. He embarked on his career as a journalist at the Waterford Star in 1904, having established an excellent reputation as a freelance provider of Gaelic games copy while pursuing a career in the wine and spirit trade. By the early 1900s Upton was politically active in nationalist circles, becoming a friend of Arthur Griffith and providing copy for the Sinn Féin newspaper. Because of his political activities, Upton was forced to resign his post at the Waterford Star in 1914. He subsequently took up employment as editor of the Kilkenny Journal, where he was to remain until 1922.

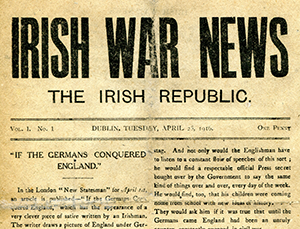

Upton also enjoyed a friendship with Joseph Stanley, the proprietor of the Gaelic Press, which published several titles that Upton wrote for or edited, including the Gaelic Athlete, Scissors and Paste, Honesty and The Spark, the latter two edited by Upton under the pen-names Gilbert Galbraith and Ed Dalton respectively. When the British confiscated the Gaelic Press printing presses on 24 March 1916, Stanley and Upton defiantly produced The Spark in Liberty Hall, guarded by the Irish Citizen Army. Upton subsequently played a role in the Easter Rising, assisting Stanley, writing copy for Irish War News and helping to distribute the bulletins. Following the end of the Rising, Upton returned to Kilkenny to continue his work at the Kilkenny Journal and for the republican cause.

In February 1925 Upton edited a relaunched Honesty for Stanley’s Gaelic Press. The new Honesty had a much wider focus than the original; still avowedly republican, it focused on the social evils of the Irish Free State and provided open access to diverse social and political opinion. Upton’s policy of open access was, in 1929, to bring him into conflict with the Fianna Fáil leadership, who used their influence to ruin his business. Consequentially, Honesty closed in February 1931. Upton quickly launched a new publication, Publicity, in May 1931, but it failed after just eight months of publication in March 1932, thereby ending Upton’s career as an editor.

Above: Irish War News, 25 April 1916—during the Rising Upton wrote copy and assisted with its distribution.

Upton delivered the history in late 1932 and copies were distributed to council members for their observations. By January 1933 they were expressing disquiet at some of its content. The details regarding the source of this conflict are frustratingly thin, outside of the assertion in the council minute book that ‘many detailed matters could be omitted’. Upton informed his family, however, that the sections to which the council had objected related to the Catholic Church. The records show that in March 1933 the history was shelved.

Given the scant records and the believed loss of all of Upton’s manuscripts, it seemed likely that the mystery of its non-publication would remain just that. In June 2013, however, a two-volume copy of what was originally thought to be an ‘unpublished thesis on the GAA’ was donated to the GAA Museum’s library and archive by the veteran GAA administrator Tom Woulfe (now deceased). While no author’s name was attached to the volumes, in 2015 they were definitively identified as Upton’s ‘lost’ work, facilitating an investigation into the reasons why the GAA shelved its publication that would reveal how Upton’s history became entangled in the complex choreography of Fianna Fáil–Vatican relations and the GAA’s organisational imperative of preserving its status and influence with Fianna Fáil and the Church, both of which were woven through the GAA’s ‘DNA’ and exercised considerable influence on its ability to pursue its ambitions.

Following Fianna Fáil’s success in the general election of 9 March 1932, de Valera immediately set about establishing its credibility with the Vatican, embedding and developing the hard-won diplomatic relations established by the previous Cumann na nGaedheal government. A central focus of de Valera’s strategy was to allay any Vatican concerns that Fianna Fáil was not a credible or safe party of government. He and his government, however, laboured under the difficulty of being perceived as a militant and potentially left-wing revolutionary party, with clearly identified links to the IRA.

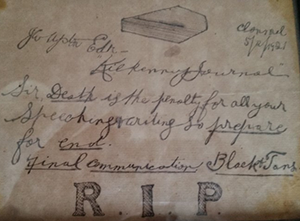

Above: A Black and Tan ‘death warrant’ issued against Upton in 1921 as a result of his Sinn Féin activism.

The Vatican’s concerns regarding the Fianna Fáil government and the IRA were twofold. Firstly, the Vatican was wary of the potential impact of Fianna Fáil’s more confrontational stance regarding Britain and the Treaty than that of its Cumann na nGaedheal predecessor and the impact that this could have on the Vatican’s relationship with Britain if it were seen to enjoy friendly relations with the Fianna Fáil government. In this regard, the Vatican was particularly concerned about any development that might compromise its policy objectives relating to establishing Catholic interests within the British Commonwealth of Nations.

Secondly, the Vatican had very real concerns regarding the IRA’s ideological affiliations in the 1930s. Elements within the IRA had developed links with the Soviet Union, developments that gave the Vatican cause for concern about the desirability of a Fianna Fáil government, given its IRA associations. The Irish hierarchy had condemned the IRA in a joint pastoral in October 1931 for attempting to ‘impose upon the Catholic soil of Ireland the same materialistic regime, with its fantastical hatred of God, as now dominates Russia and threatens to dominate Spain’.

From Fianna Fáil’s perspective, it was vital that the Vatican understood that it was a responsible political party, an exercise that would require consummate diplomacy. De Valera, in furtherance of this end, set about heading a delegation to Rome for the ‘Holy Year’ celebrations in May 1933. De Valera’s proposed visit was fraught with diplomatic complexity, as Vatican officials were concerned that he was seeking to use the Holy Year for propaganda that could damage Anglo-Vatican relations. It was during the febrile diplomatic activity building up to de Valera’s trip and his calling of the snap election in January 1933, which consolidated Fianna Fáil’s hold on power, that Upton delivered the draft of his history to the GAA council. The importance of not opening old wounds between republicans and the Church was not lost on the council, and to this end pressure was put on Upton to redact the sections of his history that could resurrect earlier memories of nationalist/Church conflict.

The offending section

While there is no chapter-and-verse ‘smoking gun’ documentation in the GAA’s archive outlining the council’s motivation in not publishing Upton’s history, Upton’s statement that it related to comments that he had made about the Church facilitated an examination of the text for any offending sections. The subsequent analysis identified only a small number of paragraphs that could have shaken the political antenna of the council on religious grounds—or, for that matter, on any other. Barring a few paragraphs in which Upton refers to his republican activity (which would not have caused the council any concern) and a couple of paragraphs referring to historic tensions between the Church and nationalist movements, the work is a romanticised hagiography of Gaelic games and the GAA, typical of the GAA journalism of the day. Indeed, even the few paragraphs that explored nationalist–Church tensions would not normally have raised the hackles of the council. When framed in the context of de Valera’s proposed diplomatic visit to Rome, however, Upton’s comments moved from a historical detail to points of contention that could impact on the realpolitik of the day.

Above: Cardinal Cullen—although Upton did not name him in his history, he was implicitly critical of the cardinal’s support for Sadlier and Keogh in the 1850s. (Irish College, Rome)

Later in the chapter, Upton went on to develop the theme of Church hierarchical collusion in anti-nationalist causes by denouncing Cullen’s successor, Cardinal McCabe. McCabe had been a deeply unpopular archbishop as a result of his stance against the Irish Parliamentary Party and its leader Parnell, whose work, he had warned, had ‘brought this country face to face with revolutionary and communistic doctrines’. Upton declared that McCabe’s attack on Parnell and the Land League was indicative of his loyalty to the British Crown over loyalty to Ireland, a loyalty that Upton asserted was a motivating force in McCabe’s hostility to the founding of the GAA. McCabe, while deeply unpopular domestically, like Cullen enjoyed very real popularity with the Vatican and the British establishment.

Notwithstanding the passage of time, the council feared that Upton’s attack could have served to reopen old wounds, wounds that had a contemporary resonance in the delicate negotiations going on between the Fianna Fáil government and the Vatican, and thereby potentially damaging the GAA’s political capital with Church and state. Ultimately, these considerations led the council to ask Upton to remove the offending sections, which he refused to do. He was unwilling to sacrifice what he viewed as truth in favour of the expedience of the political choreography of Church–state relations. Hence the council decided not to proceed with the publication of the history. Nevertheless, the events surrounding its non-publication, facilitated by the ‘rediscovery’ of this ‘lost’ text, tell us far more about the real history of the GAA than the ‘official history’ contained in the vast majority of its pages. James W. Upton died in Waterford in 1956, aged 83.

Tony Keating is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Health and Social Care, Edge Hill University, Lancashire; Mark Reynolds is the archivist at the GAA Museum, Croke Park.

FURTHER READING

- A. Keating, ‘A politically inconvenient aspect of history: the unpublished official history of the Gaelic Athletic Association of 1934’, Sport in History 37 (4) (2017), 448–68.