An Misean sa tSín [The China Mission]

Published in Issue 4 (July/August 2017), Reviews, Volume 25Esras Films (funded by the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland)

TG4, 13, 20, 27 March, 3 April 2017

By Peter Kelly

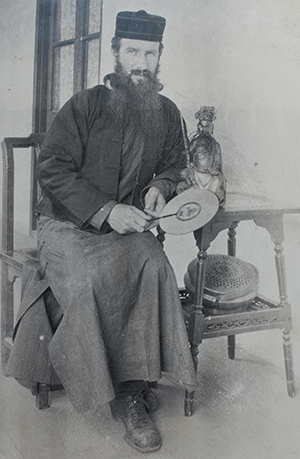

The tall, balding young Irishman at the centre of the photograph is Fr Thomas Quinlan. From Tipperary and a passionate devotee of Gaelic games, Quinlan set up a hurling team at the Columban College in Hanyang, China. He was one of seventeen newly ordained Columban missionary priests who arrived in China in 1920, the first group of a newly established missionary order which began as the Maynooth Mission to China (later the Columban Fathers). They arrived in China at a time of political chaos, famine, floods and war. China today is an economic superpower with the purchasing clout of 1.2 billion consumers. At a time when virtually every country on the planet is attempting to forge economic and cultural ties with China, Ireland can claim a 100-year-old relationship that is not tainted by colonialism and financial exploitation. From 1920 to 1954, hundreds of Irish men and women served as Roman Catholic missionaries in China and worked in social, pastoral and disaster relief services at an extraordinarily turbulent, tragic but fascinating period of Chinese history. And yet, whatever about their good works, sending Catholic missionaries to China in the 1920s raises important issues of cultural imperialism.

Above: Fr Thomas Quinlan from Tipperary with the Columban College hurling team in Hanyang, China, c. 1920s.

In the TG4 series of short documentaries, An Misean sa tSín, broadcast in March/April last, our TV production company had the opportunity to explore the issues and chronicle the experiences of Irish missionaries in China. We also set out to situate the Irish missionary effort in the context of China’s dramatic twentieth-century history. It was an opportunity made possible for television by the availability of copious archival sources from the collections of the Columban Fathers and Columban Sisters. Yes, the archives contain letters, diaries, reports and the Columban magazine, The Far East, which began publication in 1918. Crucially, however, there are also photographs and film documenting the mission—evidence of the very twentieth-century history of the mission project and the modern communications strategy of the missionary orders. The very arrival of the first missionaries in Shanghai in 1920 is captured on film, and they are shown riding in rickshaws and waving to the folks back home. They were going to have a bumpy ride. China in the early decades of the twentieth century was not at peace. Two thousand years of imperial rule ended, as province after province declared itself no longer loyal to the Qing government. A democratic republic was declared in 1911, but a single government struggled to assert authority over the country; regions were ruled by army generals and violence frequently broke out between these rival warlords. The rivalry eventually split along ideological lines, and civil war between Nationalists and Communists broke out in 1927. The pace of change, the scale of the impacts and the violent events are truly epic. The Irish missionaries were caught, physically and metaphorically, in the eye of this maelstrom. Some would be killed. Situating Irish people at the centre of dramatic world events and having motion picture film as evidence proved a major help for us in making the story accessible to the viewer.

Why China? Once the post-Famine Catholic revival got under way in Ireland, an increasing flood of vocations to religious life became an overflow. The excess of religious went abroad to serve the diaspora or joined Continental missionary orders to convert pagans in the colonies. Thirty-year-old Fr Edward Galvin from County Cork was working in New York in 1912 when he was alerted to the need for missionaries in China. So, rather ambitiously, he headed off to convert the Chinese to Christianity. He began working among communities that had known Christianity/Catholicism since the sixteenth century. His numerous letters home describe his experiences and reveal how he was captivated by Chinese culture, admitting ‘… I am more Chinese than Irish by this time’. Galvin, however, was frustrated that he had no opportunity to convert the ‘pagans’. According to the theology of the times, there could be no salvation unless a person was baptised a Christian. Galvin returned to Ireland in 1916 with the ambition of establishing a distinctively Irish missionary society dedicated to the conversion of China. He partnered with Fr John Blowick, a young professor from Maynooth, and the two campaigned successfully to set up the first indigenous Irish Catholic missionary order, which they named after St Columban. Blowick ran the missionary seminary and Galvin returned to China.

Above: Young Columban Fathers and Sisters heading to China aboard the Bremen.

The context of the times is significant, and several of the contributors interviewed for the documentary comment on what was happening in Ireland—and in China. Dr Isabella Jackson of Trinity College, Dublin, offered a perspective on the surprising similarities, as two young nations explored new politics, literary movements and asserted a national identity. While the men and women of 1916 dedicated their lives to the creation of a new state, other young Irishmen of the same generation chose a different life of service at the other side of the world. Fr Cyril Lovett, former editor of The Far East, linked the idealism of Irish nationalism with the idealism of going abroad to spread the Gospel.

Of course, the efforts of Christian missionaries are generally associated with European colonialism and the subject is laden with issues of cultural and spiritual imperialism. In China, European colonial initiatives were particularly unwelcome. The Irish missionary effort may appear no different to the pattern of their colonial predecessors: set up a church, a school and a clinic, then engage with local élites in the expectation that the masses would follow. Yet there are reasons to suggest that the Columban approach was different. Irish missionaries tended to work in rural China among subsistence farmers rather than urban élites (most Columbans were themselves from simple farming backgrounds, enabling an empathy between priest and parishioner). The Irish also tried to dissociate themselves from the colonial powers; as young Irish people in the early years of the Irish Free State, they used every opportunity to show that they were not British. On viewing the photograph of the 1921 Hanyang hurling team, Dr Ciarán Ó Neill, Professor of Modern Irish History at Trinity, commented in the documentary: ‘… they are talking about what is distinctively Irish about their mission … this isn’t a cricket bat, this is a hurl. This is Irish, it is not British.’

Perhaps more interesting are the conclusions of Chinese historian Shan Yuwu, who researched the Columban archives. He notes how the Irish missionaries hated colonialism and concludes that the Columbans deeply sympathised with the Chinese people. Every year from 1920 onwards, a new class of c. 25 Columban priests were ordained and went to China. From 1926, with the establishment of the Columban Sisters, groups of newly professed sisters joined them.

The Columban Sisters brought particular skills with them: they were teachers and nurses, and some were doctors. These skills proved invaluable when the Yangtze River burst its banks in the spring of 1931, flooding an area twice the size of Ireland. At least two million died, with some estimates suggesting that four million lives were lost. Either way, it was—and still is—the worst natural disaster in human history. Bishop Edward Galvin was put in charge of the official emergency relief committee in the tri-city area of Hanyang, Hankow and Wuchan on the Yangtze (now called Wuhan), organising clinics in the refugee camps and coordinating food supplies. The missionaries proved to be an important link to the outside world, raising funds for flood victims. China, which was traditionally hostile to foreign intervention, welcomed the international help.

The Far East reported on the flood relief efforts:

‘God alone knows what is in store for these three cities … people are crowding in from the country—an endless stream of refugees … 23 million people that will have to be fed for at least six months.’

Such emphasis on humanitarian work was unusual in Catholic missionary activity in the 1930s; it would be the 1960s before human development rather than spiritual salvation would become the principal narrative of Irish missionary work in other territories.

Above: The Columban Sisters brought particular skills with them—they were teachers and nurses, and some were doctors.

Chinese historian Shan Yuwu acknowledged the impact of the Irish relief work during the 1931 floods and commented on how this contribution enabled the local people to accept the Catholic Church; war and disaster are unfortunate for the nation, he argues, but the development of religion benefits. This observation reflects the research undertaken by Fr Neil Collins, who has written the most recent history of the Columban Fathers. Fr Collins’s book gathered statistics from reports sent back to Ireland on the numbers baptised, attending Mass and confession. By these measures, and despite civil war, floods, famine and disease, the Irish mission in China made significant progress from 1931 to 1940.

The next tragedy to befall China was the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931 was the precursor to a full-scale invasion in 1937 and led to the deaths of at least fourteen million Chinese. The Japanese Imperial Army has an appalling war-crime record in China—the most infamous incident is the six-week episode of mass murder and mass rape committed against the residents of Nanking (Nanjing today). As many as 300,000 are believed to have been killed.

Above: The Yangtze River burst its banks in the spring of 1931, flooding an area twice the size of Ireland. Bishop Edward Galvin was put in charge of the official emergency relief committee in the tri-city area of Hanyang, Hankow and Wuchan.

During the Japanese invasion, the Irish missionaries found themselves in occupied and unoccupied territory. But everyone suffers in war—death, air raids, destruction and suffering were daily occurrences endured all over China. And then the war escalated after the United States joined the Allies after Pearl Harbour in 1941. The minor details and the local impact of these epic events are all chronicled in the missionary archives.

The defeat of Japan in 1945 brought an end to the Second World War in Asia. In China there was a mood of optimism and talk of peace and prosperity. The Irish missionary centres were rejuvenated with new personnel, and an ambitious programme of expansion of church schools and hospitals got under way. The Chinese civil war between the Nationalists and Communists was unfinished business, however. Despite a truce during the Japanese occupation, and despite efforts to negotiate a peace, China suffered four more years of brutal civil war before the eventual Communist victory in 1949. It was not good news for foreign Christian missionaries. With the declaration of the People’s Republic of China, the Communist Party declared war on religion, and persecuted foreigners in particular. Irish missionaries were arrested and imprisoned; by 1954 all had been expelled. Hundreds of Chinese Catholic clergy were tortured and imprisoned; 128 Chinese priests are known to have been killed.

Above: Fr Edward (later Bishop) Galvin—‘… I am more Chinese than Irish by this time’. Along with Fr John Blowick of Maynooth, Galvin founded the Missionary Society of St Columban in 1916.

As television producers, we are very grateful that since the foundation of this mission effort in China the Irish missionaries were documenting their work there. They were witnesses to and participants in political turmoil, famine, disease, civil war and world war. They created a detailed chronology of events, with diaries and letters providing personal perspectives. After so much of China’s past was erased in the Cultural Revolution, the historical significance of the Irish missionary collections is now recognised (inside and outside China) as an extremely valuable archive of twentieth-century Chinese history. Indeed, the archives here are the reason historian Shan Yuwu came to Ireland in the first place—further evidence of a particular relationship between Ireland and China that has a 100-year-old history.

Peter Kelly is a television producer and CEO of Esras Films Ltd.

FURTHER READING

N. Collins, The splendid cause (Dublin, 2009).

Revd R.D. Degnan, ‘The 14th Air Force remembers the Columban Missions in China’, The Far East (USA edn), October 1946.

E. Fischer, Maybe a second spring: the story of the Missionary Sisters of St Columban in China (New York, 1983).