McCarthyism, Catholicism and Ireland

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2017), Volume 25Irish and Irish-American Catholic admiration for McCarthy, while widespread, was far from universal.

By Gerard Madden

When attendees gathered to hear Joseph McCarthy, the young junior senator for Wisconsin, address the Republican Women’s Club of Wheeling, West Virginia, on 9 February 1950, little did they realise that they were about to witness one of the most important events of the emerging Cold War. Although anti-communism had been a theme of McCarthy’s political activities before February 1950, it was not until Wheeling, where he dramatically produced a list of 205 alleged communists working in the US State Department, that he became a truly national—and international—figure.

Like no other politician, McCarthy succeeded in tapping into the broader anti-communist anxieties then prevalent in the United States, which had been heightened by the conviction for perjury of Alger Hiss, a former State Department official accused of Soviet espionage, two weeks before the Wheeling speech. Until his ignominious fall from grace in 1954, when, amidst increasing criticism, he was censured in the Senate by a coalition of Democrats and moderate Republicans, McCarthy was a major figure in American politics. His anti-communist speeches and hearings in the Senate gifted the English language a term—McCarthyism—synonymous with the particularly bullying and reckless anti-communism that he espoused. The junior senator’s claims attracted praise and criticism both in the United States and outside it—including in Ireland, the land of his ancestors, where anti-communist sentiment also ran deep.

American Catholicism in the immediate post-war era was marked by a heightened emphasis on anti-communism, as Pope Pius XII increasingly viewed the United States as an ally against the anti-clerical policies of the Eastern Bloc. Like their fellow Catholics, and American society more broadly, most Irish-American Catholics in the early Cold War period were imbued with a strong anti-communism. Traditional Irish-American Catholic bodies like the Ancient Order of Hibernians embraced anti-communism in the post-war years, the organisation passing a motion in 1946 calling for the removal of ‘every red, fascist and Communist fellow traveler from all government agencies, all schools, and all labor unions in the United States of America’.

Above: Senator Joseph McCarthy at a hearing of the US Senate’s Subcommittee on Investigations, 3 May 1954. (AP)

Seldom invoked his religion

Both McCarthy’s dutiful Mass attendance and his Irish background appear, however, to have been only incidental factors in motivating his anti-communism. He seldom invoked his religion when making anti-communist speeches and was reticent about mentioning it publicly at all, telling Clement Zablocki, a Wisconsin Democratic congressman, that ‘I’m a good Catholic, but not one of your “candle-lighting” Catholics’. There was little room for Irish Catholic ethnic politics in McCarthy’s rural Wisconsin heartland, where he emphasised his opposition to the Soviet Union’s post-war occupation of eastern Germany to the state’s large German-American community.

Nonetheless, given the Catholic Church’s vehement anti-communism in the early Cold War, McCarthy’s anti-communism was commonly associated with his Catholicism by others, and much of his support came from Irish Catholics in both the laity and the hierarchy. In Donald Crosby’s words, many American liberals saw ‘connections between McCarthy and the Catholic Church, connections that never existed’. Many Irish-American Catholics in turn became increasingly entrenched in their support for McCarthy, as they viewed public criticism of him by non-Catholics as being motivated by the anti-Catholic attitudes that many American Protestants still held in the years before John F. Kennedy became president. Nevertheless, McCarthy’s 1946 accusation that his opponent in that year’s Wisconsin Senate race, Howard McMurray, was a communist sympathiser was strongly criticised by Bernard Sheil, Catholic auxiliary bishop of Chicago—an early sign that Irish-American Catholic admiration for McCarthy, while widespread, would be far from universal.

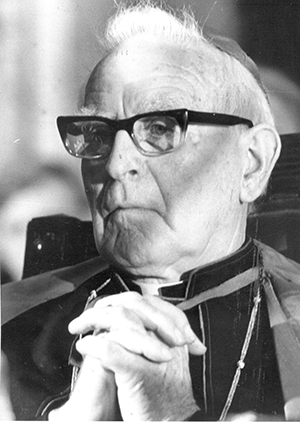

Above: Bishop Cornelius Lucey of Cork—as McCarthy found himself the target of increasing public criticism in 1954, Lucey vigorously defended him after a US visit that year. (Cork Examiner)

The anti-communism of Irish-America was echoed in Ireland itself. While a peripheral actor in the Cold War, Ireland, owing to the influence of the Catholic Church, paid close attention to the plight of the Church internationally amidst communism’s international expansion in the post-war years. The trial and imprisonment of Archbishop Stepinac of Yugoslavia in 1946 and of Cardinal Mindszenty of Hungary in 1948 prompted widespread anger in Ireland, and tens of thousands of people thronged Dublin’s O’Connell Street on 1 May 1949 to protest their detentions. Expulsions, imprisonments and killings of Irish Catholic missionaries in China and Korea also hardened Irish Catholic opinion against communism, while revelations of communist espionage in Britain, Canada and the United States attracted considerable Irish attention.

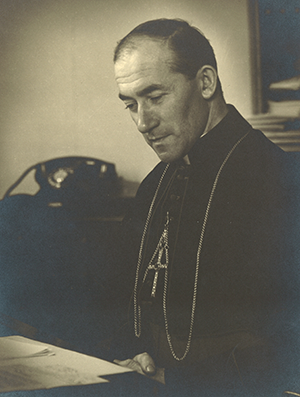

There was also an anxiety on the part of the Irish Catholic hierarchy about the potential growth of communism in Ireland, despite the fact that the Irish Workers’ League (IWL), as Irish communists reconstituted themselves in 1948, never had more than a few dozen members. In 1954 Archbishop John Charles McQuaid of Dublin set up a ‘Vigilance Committee’ tasked with monitoring communist activity. The trade union movement, unemployed campaigners, the Irish Association for Civil Liberties, the Irish Housewives’ Association, and pacifist and nuclear disarmament campaigns were amongst those who attracted the committee’s attention. McQuaid’s anti-communism was felt equally strongly by fellow members of the hierarchy like Cardinal John D’Alton of Armagh, Bishop Michael Browne of Galway and Bishop Cornelius Lucey of Cork, and was crucial in motivating them to oppose Noël Browne’s 1951 Mother and Child Scheme, which the hierarchy viewed as a slippery slope to communism.

Above: Archbishop John Charles McQuaid of Dublin—in 1954 he set up a ‘Vigilance Committee’ tasked with monitoring communist activity in Ireland. (Dublin Diocesan Archives)

‘a subversive conspiracy aimed at the destruction of the state. It could not be discovered by ordinary methods, and Senator McCarthy has shown a great ability in discovering and securing very accurate information. He is in no sense the kind of witch-hunter he is represented to be.’

As McCarthy found himself the target of increasing public criticism in 1954, Lucey vigorously defended him after a US visit that year, asserting that McCarthy had ‘an unsavoury job because [communists] are a slippery unsavoury lot, but surely it is a job that should be done if people value the free way of life’. Unlike Browne, Lucey acknowledged that ‘not all his suspects have been found guilty’, but nonetheless defended McCarthy’s work overall, claiming that ‘people I met in America were shocked at the way McCarthy has been condemned without a hearing in Ireland’.

Anti-McCarthy Catholic opinion

The Standard, the most prominent Catholic newspaper of that era, was staunchly anti-communist, and regularly posted stories about IWL members and their activities. Its attention to McCarthy heightened in the latter part of his career, particularly as he encountered increased criticism in 1954. In June it highlighted a statement by Archbishop Richard Cushing of Boston on McCarthy, which denied that American Catholics were divided in their response to the senator and assured reporters that anyone ‘interested in keeping Communism in all its phrases and forms from uprooting our traditions’ had Cushing’s sympathy. While the Standard’s reports on McCarthy highlighted both praise and criticism from US Catholics, the latter greatly outweighed the former. Joseph Marling, the auxiliary bishop of Kansas City, told a Standard reporter while on a visit to his ancestors’ home place in Strabane, Co. Tyrone, in the same month that McCarthy had ‘awakened many Americans’ to the fact that communists ‘in high places in the government could do a lot of harm’. Marling asserted that Europeans possessed a distorted image of McCarthy, regretting that ‘the people of the continent are getting such a false picture of America’.

An October piece by a Francis Fytton on McCarthy, while acknowledging that ‘certainly McCarthy has exaggerated the dangers of communist infiltration’, broadly defended him, assuring readers that they could be ‘certain’ that McCarthy would ‘face his trial with courage and integrity’. Anti-McCarthy pieces, which the Standard syndicated, included one the same month by Stephen Ryan, an English professor in St Francis Xavier University, New Orleans. Drawing on anti-McCarthy statements by Bishop Sheil, who remained a determined opponent of McCarthy throughout the latter’s career, Ryan correctly predicted that McCarthy’s demise was imminent: ‘We have seen his like before—the late Huey Long was a good example—and they have all run their brief course and faded away’.

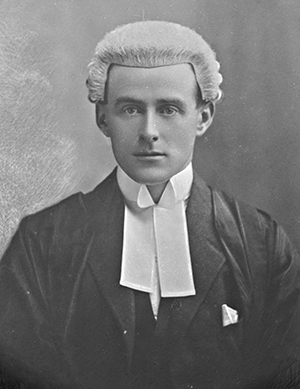

Above: John J. Hearne as a young barrister. As Irish ambassador to the United States from 1950 to 1960, he was a key figure in shaping the Irish Department of External Affairs’ reactions to McCarthy’s career. (NLI)

Irish diplomats abroad kept abreast of Cold War events, and were instructed by Dublin to send home what information they had on claims of communist infiltration and anti-communist legislation in countries such as Australia, Canada and the United States. John J. Hearne, the Irish ambassador to the United States from 1950 to 1960, was a key figure in shaping the Irish Department of External Affairs’ reactions to McCarthy’s career. Hearne’s time in the United States, which coincided with the period of McCarthy’s rise and fall, saw him frequently report to Dublin on allegations of communist subversion, and in this vein he met leading politicians and church leaders like Cardinal Francis Spellman. Spellman was a noted anti-communist—he informed America in June 1946 that ‘the first loyalty of every American is vigilantly to weed out and counteract Communism and convert American Communists to Americanism’—and he expressed profound pessimism to Hearne about the United States’ readiness to combat the communist threat.

Hearne payed close attention to McCarthy’s career, particularly after the Tyndings Committee, a Senate subcommittee formed in 1950 and consisting mainly of Democrats, vocally criticised McCarthy’s accusations. He took seriously McCarthy’s claims that the United States had been penetrated by communists, asserting that during the Second World War, when the United States and the Soviet Union had been allies, the ideology had ‘grown secretly like a cancer’, with the Soviet Union gaining the admiration of west-coast intellectuals and pro-Soviet friendship societies given space to operate with a degree of respectability. Hearne echoed broader Irish-American opinion by viewing ‘New England Episcopalians’ as opponents of McCarthy. The senator’s defeat, Hearne felt, would strengthen American communism.

The Senate’s December 1954 vote to censure McCarthy for his activities was a serious blow to his influence, however. While most pro-McCarthy Catholic publications remained defensive of him initially, even they gradually stopped reporting his activities; in Donald Crosby’s words, ‘seldom in American political history has a major political figure descended into oblivion as quickly and with such finality’. The controversies around McCarthy briefly revived when he died in 1957, at the untimely age of 47. Most Irish newspapers issued brief, dispassionate reports of McCarthy’s death. Indicative was the response of the Cork Examiner, which noted that he had been ‘praised in some American quarters as the greatest patriot since George Washington, and denounced in others as one of the most dangerous demagogues that the United States has ever seen’. Fiat, the newspaper of Maria Duce, predictably eulogised McCarthy. It also condemned organisations which it claimed had disrespected McCarthy, such as the Irish Association for Civil Liberties, which it ‘need hardly remind readers … followed an anti-McCarthy line’, and Radio Éireann and Irish newspapers more broadly: ‘It was mentioned almost perfunctorily. In the Russian press at least it was recognised that the sickle of death had cut down the most formidable enemy of communism in the United States.’ The relatively low-key response that McCarthy’s death provoked in Ireland overall, however, should not obscure the attention he received at his height, and his demagogic campaigning prompts unsettling parallels with American politics today.

Gerard Madden is an Irish Research Council-funded Ph.D student in NUI Galway.

Read More:

McCarthy’s Irish background

FURTHER READING

S. Cronin, Washington’s Irish policy, 1916–1986: independence, partition and neutrality (Dublin, 1987).

D.F. Crosby, God, church and flag: Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and the Catholic Church, 1950–1957 (Chapel Hill, 1978).

J. De Haan, ‘McQuaid’s old granny: Úna Byrne’s mission to clean up the Irish Housewives Association’, History Ireland 23 (1) (2015), 42–4.