The greatest Famine film never made

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2017), Volume 25BLACK ’47, WHICH COMMENCES SHOOTING SHORTLY, IS NOT THE FIRST FAMINE-THEMED FILM TO BE ENVISAGED

By Bryce Evans

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the publication of Liam O’Flaherty’s novel Famine, set during Ireland’s Great Hunger (1845–51). O’Flaherty’s literary contemporary Seán O’Faoláin called Famine ‘tremendous’, ‘biblical’, containing ‘a compression of emotion only to be found in the great books’. Typical cover-endorsement hyperbole it wasn’t: Famine has stood the test of time as a terrific read, one that addresses Ireland’s mid-century catastrophe directly and unsentimentally. But O’Flaherty wanted more than just literary success—much more: he wanted a Hollywood blockbuster. It was a dream that would take him to Tinseltown and to the verge of mental collapse.

Ford and O’Flaherty

O’Flaherty was born on the Aran Islands in 1896. In 1915, aged nineteen, he joined the British Army. He survived the war but at the nightmarish price of shell-shock, which earned him a discharge in May 1918. In his own words, he then ‘set out to conquer the world, from the Aran Islands’. A jack of all trades with an abiding wanderlust, O’Flaherty held a succession of jobs, including trimmer on a coal steamer bound for Brazil, lumberjack, ‘hobo carpenter’, miner in Canada and labourer in a Boston biscuit factory. He returned to Ireland in 1921 a confirmed socialist.

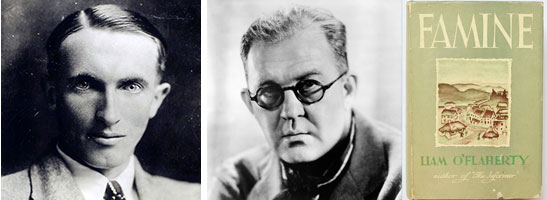

Above: Liam O’Flaherty—his 1937 novel Famine (first edition, inset) was dedicated to film director John Ford (right).

O’Flaherty, then, had lived a full life before he started work on Famine, aged 37, in 1933. It was a life that had left its scars. Those who came across this islandman were struck by his lean frame, clipped haircut and searing blue eyes: a clue to the intensity of his character. Owing to the lasting effects of shell-shock, O’Flaherty’s mental state was precarious; he was irascible, self-important, eccentric and always on the move. Perhaps inevitably, then, he gravitated to Hollywood and assumed the latest of his many incarnations: movie scriptwriter.

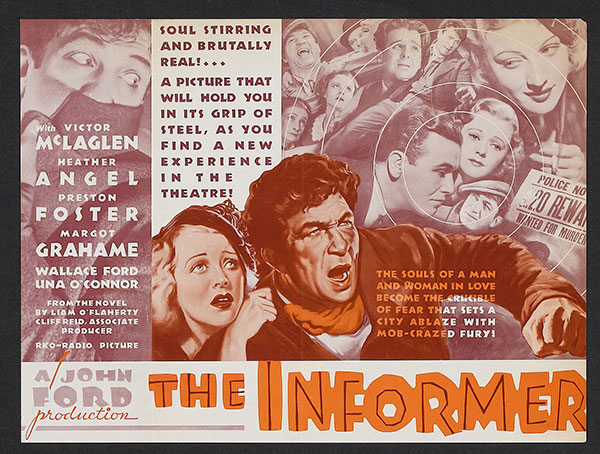

It was in this role that Liam O’Flaherty met the celebrated director John Ford. The two men hit it off immediately. Although they did not share the same politics, they were naturally attracted to one another’s work and shared common ancestry to boot. In 1935 Ford directed a version of O’Flaherty’s novel The Informer, starring Victor McLaglen. Fiercely proud of his impeccable west of Ireland roots, Ford liked to Gaelicise his name as Seán Aloysius Ó Fearna and named the 110ft yacht where he worked on movie projects and boozed with Hollywood A-listers Araner, in dedication to his mother. An avid reader of literature and history, Ford possessed a large dose of Famine-inspired historical grievance to match his hard-drinking Irishman image. In 1952, during the filming of the East African hunting romp Mogambo, Ford came across an Englishman on the set, whom he treated cruelly for weeks. The reason, the bemused cast and crew later discovered, was that the Englishman’s antecedents had been the owners of a large Galway estate on which a number of Ford’s ancestors had laboured before allegedly being forced onto Famine ships. During a break in filming for a Tanzanian safari, Ford wrote to Galwegian movie mogul Michael Morris (Lord Killanin) of ‘an awful SHIT named Colonel Hartlaud-Mahon here’, adding that he was ‘acting as our camp manager’. ‘= Walcourt? Galway I think. Check.’ Ford, then, was deeply motivated by Irish history and this was his way of achieving historical restitution of sorts. Killanin, who would divide his time between Spiddal and Bel Air, was more than a professional contact for Ford; he was a close friend who provided the Irish-American director with a sentimental link back to the ‘old country’. Importantly for O’Flaherty, he was (like Ford) a great admirer of new Irish writing, particularly Famine.

Meanwhile, the Aran author was now ‘living the dream’, dabbling in screenwriting for Hollywood and hanging out with the cream of Hollywood talent on the Araner. He struck up a friendship with Zeppo Marx, the youngest of the Marx brothers, and they enjoyed holding zany chats in a mixture of Yiddish and Gaelic, never comprehending one another fully.

But Famine always loomed as the greater project for O’Flaherty. Importantly, it was also a work in which Ford had expressed his faith. O’Flaherty wrote to Ford in June 1935, excusing himself ‘for dashing off the way I did without saying goodbye’ but explaining that he had to ‘get back home to put Famine on the stocks’. Capturing the closeness that had developed between them, he continued: ‘I think Famine is going to be great, and you need never feel ashamed, I assure you, that it’s dedicated to you. I’m going to hammer out every word from the depths of my soul.’

Above: In 1935 Ford directed a version of O’Flaherty’s novel The Informer, starring Victor McLaglen.

Famine, the novel

In 1937 O’Flaherty came up with the goods: Famine was released, complete with dedication to John Ford. As promised, it was great. Despite being turned down by a succession of publishers who thought it too gloomy, Famine is not a maudlin novel. Hope and resilience are embodied in the story’s beautiful heroine, young mother Mary Kilmartin, who gives birth during the blight but is determined that her child will not perish. While condemning the ‘tyrant queen’, Victoria, the book is most scathing in its treatment of home-grown gombeen men and is open to the idea that merely to blame the English for the Famine is simplistic.

The novel was made for film—unashamedly so, in fact. Inside the dust-jacket of the first edition was a direct plea that it be adapted as a movie. The busy Ford, however, was not taking the bait. So in 1939 O’Flaherty wrote to his director cousin to tell him about interest in Famine from a French film company, who had promised the director 12m francs to direct it. Ford, however, was ‘filled up’ for the year. ‘It would have been fun if you could have come,’ wrote O’Flaherty, sounding increasingly like a lonely schoolchild shunned by the more popular kid, ‘they would have got out the whole town to welcome you.’ Further letters reinforced O’Flaherty’s devotion to Ford. ‘What do you advise me to do about Famine? … Do you think Hollywood will let you do it?’ Ford, however, was by this point preoccupied with a contemporary plight reminiscent of Ireland’s Great Hunger.

Dust Bowl drama

In the 1930s in the USA a widespread fall in agricultural prices was accompanied by a series of dust storms on the prairies. The Dust Bowl phenomenon brought desperation, desolation and mass migration. Immortalised by the characters of John Steinbeck, the agricultural crisis of America’s Great Depression featured prominently in the Atlantic consciousness as the centenary of Ireland’s Great Famine loomed. The Pulitzer Prize-winning evocation of this in The Grapes of Wrath (1939) prompted Ford to translate it to film in 1940. Explaining why he had chosen to make the film, Ford made the link explicit, claiming that he made the film because it ‘was similar to the famine in Ireland, when they threw the people off the land and left them wandering on the roads to starve’.

Above: Henry Fonda in Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939)—Ford claimed that it ‘was similar to the famine in Ireland, when they threw the people off the land and left them wandering on the roads to starve’.

The film’s commercial success was to catapult Ford towards Tobacco Road, a 1941 film that featured a family of tenant farmers facing eviction by the bank. But this time they were comical: inbred, turnip-munching savages, dirty and feckless. By 1941, therefore, Hollywood had done famine-esque suffering, first as tragedy, then as farce. The conception of The Grapes of Wrath as a famine film meant that Ford never made what would almost certainly have been the greatest movie about the Great Famine, a film that would have taken the unequivocal title Famine from O’Flaherty’s masterpiece novel and translated its powerful scenes onto reel. Perhaps, then, by 1940 the great film of the Irish Famine had already been made: starring Henry Fonda, and set on the plains of Oklahoma rather than the wilds of Connacht.

Hollywood Cemetery

But just try telling that to O’Flaherty, who was still Stateside and still harbouring the idea of Famine appearing in bright lights above cinema foyers up and down America. There were mounting problems with his vision, however. It wasn’t just that the topic had been ‘done’ in The Grapes of Wrath, and it wasn’t the fact that starvation held little natural commercial appeal anyway. It was that O’Flaherty was rapidly alienating himself from some of Hollywood’s big hitters.

O’Flaherty’s left-wing contempt for Hollywood found its way into his 1935 novel about the money-grubbing shallowness of the American film industry, Hollywood Cemetery. In a case of life imitating art, O’Flaherty soon went about offending Hollywood’s producers in his own inimitable way. In 1941 Ford brought him in to scriptwrite How Green Was My Valley, but O’Flaherty pulled out halfway through. The producer, Daryl F. Zanuck, consequently refused to pay him, claiming breach of contract. But O’Flaherty, who was always in debt and had once complained to Ford that ‘Jews are funny people’, needed the money. Returning to the studio the following day armed with a pistol, he marched over to Zanuck and held the gun to the terrified producer’s head.

It now seemed that for O’Flaherty, perpetually in want of money to buy food, get drunk, fix his teeth or settle one debt or another, the definitive Hollywood version of Famine—his Famine—would remain the great dream.

Four Provinces Productions

As 1951—the last of the Famine centenary years—came around, however, it seemed that the dream might finally become reality. In that year Lord Killanin established an Irish film studio, Four Provinces Productions, with John Ford on the board. When Four Provinces was set up, their first ‘tentative idea’ was to adapt Famine. This offered O’Flaherty a clear route around the opposition of Hollywood’s producers. The only trouble was getting hold of him. The restless author, who was unable to stay in one place for any prolonged period of time, was, in his own words, ‘a lost puppy’. And like a lost puppy, O’Flaherty tended to roam unpredictably, with Killanin’s letters to him at diverse hotel addresses all going unanswered.

One day, by chance, Killanin bumped into the wayward O’Flaherty on the King’s Road in London. Killanin assured him that he and Ford still had in mind an adaptation of Famine and wrote to Ford to tell him about the meeting, reporting that O’Flaherty was still ‘very excited’ about the project.

This time, though, Ford admitted his ‘misgivings’ about Famine. The 57-year-old director was recovering from a double hernia at the time, an ailment that (with typical machismo) he attributed to jumping out of helicopters as part of his US naval duties. It was not so much the subject-matter but the cost that alarmed Ford. He told Killanin that adapting Famine ‘would entail rather elaborate production and layout’.

Ford still wanted to make an Irish film that would be a ‘grand historical document’ but at that stage was envisaging a lower-budget War of Independence film. He had talked to Maureen O’Hara about it, he told Killanin, ‘and after a three-hour hysterical outburst … she agreed, due to my persuasive powers and a swift kick in the arse’. This film was never to see the light of day; neither was an alternative Irish epic, the life of Charles Stewart Parnell, penned by senior Irish civil servant Conor Cruise O’Brien. In any case, Famine was clearly no longer the priority for Ford.

Above: Maureen O’Hara and John Wayne on the set of The Quiet Man—a much safer commercial proposition for Ford.

The great ‘Irish film’

Shortly after Ford turned down Famine, his most famous ‘Irish film’ came out. The Quiet Man, starring John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, was a much safer commercial proposition and went on to earn a handsome $3.8 million at the box office. After filming finished, Ford would complain to Killanin that he hadn’t ‘seen or talked to O’Hara since we finished. She spends most of her time in Mexico with her coloured millionaire. She’s a greedy bitch and I wonder if she’d accept any terms.’ But he also had to admit that ‘of course her name in an Irish film has value’. This last reflection is illustrative: to Ford and Four Provinces Productions O’Hara had commercial value and, as usual, money was paramount. It was an overriding priority with which the wily O’Flaherty was very familiar and to which he was not willing to conform. It is easy to see why. The all-too-obvious cultural branding of the company saw Killanin and Ford adapt more commercially viable paddy-whackery. Four Provinces even included miniature shillelaghs in their company Christmas cards. For O’Flaherty, who wanted to see his novel adapted seriously, the vacuity of it all was nauseating.

As his Irish Times obituary put it, Ford ‘was basically a simple man, with simple, old-fashioned values which sometimes betrayed him into excesses of sentimentality. But on his home ground, the Wild West or the Deep South, his mastery was complete.’ The same might have applied to the wild west of Connemara, but it was not to be. There would be attempts to bring Famine to the screen right up until O’Flaherty’s death in 1984. All were unsuccessful. A pity, since a film version of Famine—hitting screens during the centenary of the Great Hunger, written by O’Flaherty, directed by Ford, and perhaps with Maureen O’Hara as lead—would almost certainly have become the seminal film about Ireland’s Great Hunger, perhaps even the seminal Irish film.

Bryce Evans is Senior Lecturer in History at Liverpool Hope University.

FURTHER READING

L. Gibbons, The quiet man (Cork, 2002).

A.A. Kelly (ed.), The letters of Liam O’Flaherty (Dublin, 1996).

L. O’Flaherty, Famine (London, 1937).