Fenians in the foothills: Patrick Doran and the Rising of 1867

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2017), Volume 25A fascinating family connection with a failed rebellion.

By Fergus Whelan

Above: Patrick Doran in 1864.

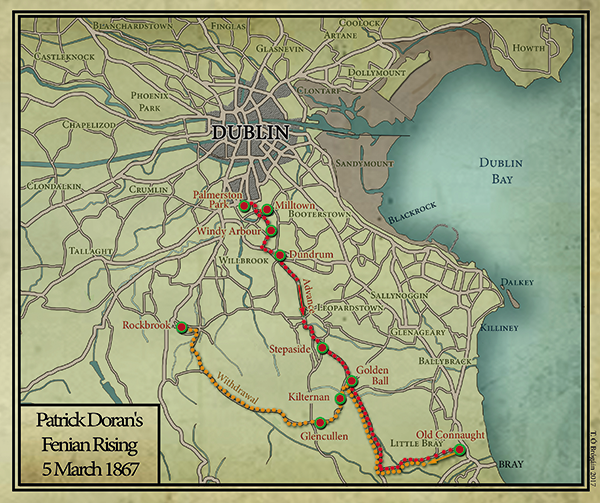

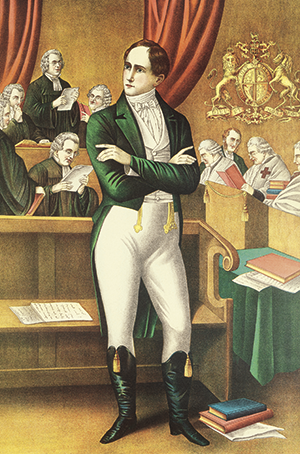

Captain Lennon shouted the orders: ‘Fall in, form fours, shoulder weapons’. The men ‘loaded their pieces, counted off and formed their column like veterans’. Many of the men carried rifles with fixed bayonets, while most of those who carried pikes also had revolvers. In their train was a horse-drawn ammunition car with 17,000 rounds of ammunition. They marched towards Milltown and the Wicklow Mountains. They flew a green flag emblazoned with the slogan ‘Remember Emmet’. Within a few shorts weeks Patrick Doran would stand in the dock in Green Street Court House, facing the same charge as Emmett, and be sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Indeed, Patrick Doran and Colonel Thomas Francis Burke, his co-accused, were the last men in British judicial history to have this sentence imposed on them.

Captain Lennon’s orders were to march into the Wicklow Mountains, to avoid major troop or police concentrations and only to engage the enemy in small actions. The plan was to draw the military out of Dublin city and for other groups of Fenians to engage in guerrilla actions in the city. There were several thousands of Fenians moving out of Dublin that night. The police noted that a large number of (horse-drawn) cars left the Coombe and the Kevin Street area. A police sergeant at Crumlin reported that ‘the Dublin road is crowded with young men, all taking the direction of Tallaght’.

Milltown

Lennon’s men took their first prisoners at Milltown. Sergeant Sheridan and three city policemen were divested of their revolvers, belts, bayonets and ammunition. Sheridan later testified that Lennon called some riflemen forward and ordered Doran to take control of the prisoners as the column marched on. At Windy Arbour the column was reinforced by a well-armed detachment under Captain John Kirwan, who assumed command of the by now 700 or so insurgents. Kirwan was also an experienced soldier who had seen action as a sergeant in the Papal Brigade against Garibaldi’s Red Shirts and Piedmont forces in 1860.

Dundrum

As the column passed Dundrum they attacked the RIC station. The fortified barracks was defended by nine policemen who refused to surrender. In the firefight Captain Kirwan was shot through the shoulder and had to be taken away. With Kirwan out of the action at Dundrum, the command again fell to Lennon. As the barracks was so near the city, however, he instructed the men not to persist with the attack but to press on towards Stepaside.

Lennon later told John Devoy that on the road to Stepaside a fourteen-year-old boy whose name he never learned joined the line, carrying a rifle on his shoulder. He proved to be one of the best fighters in the party. My father’s family lore had it that his great-uncle Topsey O’Connor, aged only twelve, had joined the Fenians at Stepaside.

Stepaside

They arrived at Stepaside at two in the morning, intending to capture the barracks. Captain Lennon stepped up and rapped on the door with the hilt of his sword and called on the police to surrender in the name of the Irish Republic. When the defenders refused, the firing started. Harry Filgate, one of the attackers, tells us:

‘Constable McIlwaine (and his men) returned the fire. We discovered that the shots came from the second floor. This enabled some of us to get right up to the building … with the aid of sledges taken from a blacksmith shop … [we] soon had the barricaded window broken in.’

The attackers threw straw into the building and threatened to set it on fire. The defenders surrendered. The Fenians burnt the records, took the arms and ammunition and marched on towards Old Connaght above Bray. They expected that their comrades from Killakee under General Halpin would already have taken Bray, but Lennon’s scouts found that Bray barracks was strongly guarded and that cavalry from Dublin were coming at their rear. Filgate claimed that they then decided to ‘retrace our steps, take to the Dublin Mountains and destroy all the police barracks we could find’. Lennon marched his men back to Golden Ball, where he requisitioned bread from Sutton’s bakery. They turned at Kilternan Cross and took the mountain road to Glencullen.

Above: The Battle of Tallaght, 5 March 1867—when Lennon realised that the main Fenian army had been routed there, he disbanded his men at Rockbrook. (Illustrated London News)

Glencullen

The column arrived there about 7am. Sergeant Sheridan testified that Lennon and Doran stepped forward and both rapped on the door of the police barracks, demanding the surrender of its occupants in the name of the Irish Republic. Constable O’Brien refused to surrender and Lennon ordered 50 riflemen forward to take the barracks. The rest of his men and his prisoners stayed out of range. A fierce fire fight ensued that lasted over an hour. The barracks was well fortified and the Fenian bullets mostly bounced off the iron shutters. Dennis Duggan, a coach-builder from Dublin, made an embrasure in the perimeter wall through which he fired. Duggan had been involved in the escape of James Stephens from Richmond Gaol in 1865. Nine years later he was involved in the famous Catalapa rescue, when six Fenian prisoners escaped from the infamous prison colony in Freemantle, Australia. Lennon singled out Duggan for his bravery that day in Glencullen, saying that he had ‘great nerve and acted with the coolness of a veteran’.

Harry Filgate was wounded at this point and Lennon ordered him to the rear to be treated by the ‘doctor’, who had remained with the ammunition van. Lennon was anxious to complete the action and join the main rebel army at Tallaght Hill. He did not know that this army had disintegrated a few hours earlier. He instructed Constable McIwaine to come to the front and tell O’Brien to surrender the barracks. McIwaine called out to O’Brien that further resistance was pointless and that the Fenians were about to shoot their prisoners and fire the barracks. O’Brien parleyed and agreed to surrender if the life of his men and the lives of the other policemen would be spared.

After the surrender, Lennon heard loud voices within the barracks and was concerned lest his men might be mistreating the prisoners. He entered with drawn revolver, saying ‘These men are prisoners of war and I will shoot any man who injures or insults them’. His men laughed and said that they were just getting a rise out of the Peelers. Outside Lennon saw an elderly priest haranguing his men, telling them to go home. A man of few words who rarely used bad language, Lennon put the revolver to the old priest’s temple and said ‘F—k off home or I will give you the contents of this’. The priest went home. Many years later, the old priest when telling the story would say: ‘That man knew his business and I’ve no hard feelings against him. If I didn’t do what I did Paul Cullen would be after my scalp, but that man knew his business.’

Disbanded at Rockbrook

Lennon commanded the police not to move for two hours. It was by now about 9am and the main Fenian army at Tallaght had already been routed. Hundreds of rebels were being rounded up in the mountains and the city. Lennon’s party marched towards Tallaght but must have heard the bad news from fleeing rebels. He disbanded his men at Rockbrook and each man chose his own route back to the city. The wounded Filgate got as far as Rathfarnham when a company of dragoons galloped by, heading in the direction the column had been. These were followed by four companies of infantry with two artillery pieces. Doran and a man called Meares were arrested making their way through Dundrum village. They were taken to Kilmainham to join the hundreds of Fenian prisoners who had been taken at Tallaght and elsewhere.

Trial

On 28 April 1867 Doran stood in the dock at Green Street, and he and Colonel Thomas Francis Burke were charged with high treason. Burke had come from America to lead the rebellion in Tipperary. He had fought for the Confederacy at Gettysburg. The defence mounted by the great Isaac Butt and John Ade Curran was of course in vain. After all the evidence and legal arguments, his lordship put on his black cap and uttered the sentence:

‘You Thomas Burke and you Patrick Doran shall be taken from this place where you now stand to the place from whence you came and on 29th May you are to be taken on a hurdle from that place to the place of execution, and that there each of you be hanged by the neck until you be dead, and that afterwards the head of each of you shall be severed from its body and the body of each of you divided into four quarters to be disposed of as her majesty and her successors feel fit and may the Lord God Almighty have mercy on your souls.’

Burke spoke first:

‘I am willing, if I have transgressed the laws, to suffer the punishment; … I ask for no mercy. My present emaciated form—my constitution somewhat shattered—it is better that my life should be brought to an end, than to drag out a miserable existence in the prison pens of Portland … But I can remember the blessing received from an aged mother’s lips, as I left her the last time. She spoke as the Spartan mother did—“Go, my boy. Return either with your shield or upon it”. This reconciles me. This gives me heart. I submit to my doom, and I hope that God will forgive me my past sins. I hope, too, that inasmuch as He has for seven hundred years, preserved Ireland, notwithstanding all the tyranny to which she has been subjected … He will also retrieve her fallen fortunes—to rise in her beauty and her majesty … the peer of any nation in the world.’

Then it was Doran’s turn:

‘I have not much to say. I cannot follow in the same strain of eloquence that my countryman and fellow patriot has expressed himself, but I may say this: I also am consigned to an early grave—cut off in the vigour of manhood by falsehoods sworn at that table false as God is true. In relation to Sheridan he sat there with a smile on his countenance and swore that I commanded the riflemen or in other words that I acted as aide de camp to one of the conspirators called Lennon … He also stated that I demanded the surrender of the barracks at Glencullen in the name of the Irish Republic. There are men … now present who could give another account of that transaction but they were not called … to prove my innocence. I never spoke to him good or bad that night; never said a word to him or any of them and was not there at all … I forgive them now as I hope God will forgive me. I have no more to say. I return my heartfelt thanks to my talented council who so ably defended me and also to my solicitor Mr Lawless.’

Above: Robert Emmet on trial at Green Street courthouse, 19 September 1803. ‘Remember Emmet’ was emblazoned on the column’s green flag, and on 28 April 1867 Patrick Doran would stand trial in the same dock, facing the same charge, and be handed the same sentence—to be hanged, drawn and quartered, later commuted to transportation for life. (Shamrock, December 1892)

The Hougoumont sailed for Freemantle with 280 convicts, including 63 Fenians. This was the last convict ship to leave the shores of Britain bound for the penal colonies. A number of Fenians, including John Boyle O’Reilly, have left us graphic descriptions of this ‘floating hell’. After 89 days of a hellish voyage, all that awaited lifers like Patrick Doran and John Boyle O’Reilly was a slow death from slave labour. O’Reilly contrived to escape, however, and Doran made it to America, probably as a result of an amnesty, but the American Fenians never let the truth get in the way of a good story. The following was the Fenian version of Patrick Doran’s arrival in America:

‘THE PACIFIC COAST

Arrival of Escaped Irish Political Prisoners from Australia.

San Francisco, January 25, 1870.

The British ship Baringer, from Australia, brings the following escaped political prisoners sent from Ireland to the British penal colonies in 1865 and 1867.

John Kenny, Dennis B. Castman, Dennis Hennessey, Maurice Figenbohm, Patrick Lehy, Thomas Fogarty, David Joyce, John Shehan, Patrick Wall, Michael Moore, David Cumming, Eugene Geary, John Walsh, Patrick Doran and Patrick Dunns.

They say that they suffered indignities such as no other country but England offers to political offenders.’

Fergus Whelan is the author of God-provoking democrat: the remarkable life of Archibald Hamilton Rowan (New Island Press, 2015).

FURTHER READING

J. Devoy, Recollections of an Irish rebel (Shannon, 1969).