JOURNALISM: Scandal and anti-Semitism in 1916: Thomas Dickson and The Eye-Opener

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2016), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 24AMONG THE MOST INFAMOUS EVENTS OF THE EASTER RISING WAS A SERIES OF MURDERS COMMITTED BY CAPTAIN J.C. BOWEN-COLTHURST. HIS MOST FAMOUS VICTIM WAS FRANCIS SHEEHY-SKEFFINGTON, SUMMARILY EXECUTED ON THE MORNING OF 26 APRIL IN PORTOBELLO BARRACKS, ALONGSIDE TWO NEWSPAPER EDITORS, PATRICK MCINTYRE AND THOMAS DICKSON. BUT WHO WAS THOMAS DICKSON?

By Conor Morrissey

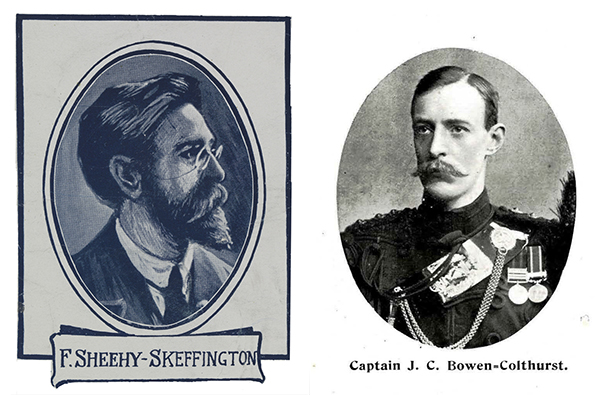

Above: Francis Sheehy-Skeffington (left), the most celebrated victim of Captain J.C. Bowen-Colthurst’s (right) three summary executions of 26 April 1916.

The murder of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington,Home Ruler, pacifist and women’s rights activist, became a cause célèbre and, alongside the execution of the dying James Connolly and the execution of Joseph Plunkett hours after his marriage to Grace Gifford, contributed to changing public opinion towards the rebels. Thomas Dickson and Patrick McIntyre,however,have been largely forgotten.

Who was Thomas Dickson?

Thomas Dickson was a convicted fraudster whose anti-Semitic and sexuallysalacious journal,The Eye-Opener,has a claim to be the most vitriolic Irish periodical published in the early decades of the twentieth century. Although the Eye-Opener’s circulation was tiny, it provides an insight into how a small minority viewed Jews and sought to police the private lives of fellow citizens. It alsohighlights the diversity of topics covered by the Dublin press during this era.

Little is known of Thomas Dickson’s early life.According to the 1891census of Scotland, he was born around 1885 in Glasgow, the son of Samuel and Annie Dickson, both of whom were Irish. Samuel Dickson worked as a plumber and gasfitter. In 1901 the family—five sons and three daughters—lived in Glebe Street,Glasgow, a tenement area. In that year Thomas, the eldest, is listed as working as an advertising agent. Dickson suffered from dwarfism and his appearance alarmed others. One contemporary account described himafter his death as ‘a Scotchman, and deformed’; Monk Gibbon, a Dublin-born British officer who was present at Portobello, described him as ‘tiny, a dwarf of about four-foot-six, a grotesque figure in a black coat with curious eyes’. He showed an early tendency for criminality: it was alleged at his libel trial in 1916 that he was convicted of a criminal offence in Glasgow in 1903.

By 1911 Dickson was living in Dublin. In the census for that year he is listed as staying as a visitor in a house in PleasantStreet, Dublin. A Catholic, he was working as a merchant. Later that year Dickson embarked on a fraud that would lead to a criminal conviction. According to testimony given at his trial in February 1912, Dickson operated the inauspiciouslynamed ‘Assurance Tea Company’ from a premises on Lower Camden Street. He adopted the unsophisticated stratagem of placing advertisements for reasonablypriced tea and 21-piece tea sets in several midland newspapers, and invited readers to send postal orders to obtain the goods.When the postal orders came in, Dickson simply pocketed the cash. The evidence suggests that this was a premeditated fraud rather than an example of an ambitious entrepreneur over-extending himself: Dickson’s landlord claimed that he saw no business done in the shop, and when he investigated he found no goods there, although there were a number of dummy packages of tea, cocoa and coffee. Dickson, who made little effort to mount a plausible defence, was convicted of obtaining money under false pretences.

The Eye-Opener

Four years later, in February 1916, undeterred by his trial and conviction, Dickson launched a more ambitious venture: a scandal sheet entitled The Eye-opener. In its first issue Dickson, its editor and seeminglyits sole contributor, promised to

‘…give public exposure to a few things that are at present very much requiring the light of day, and at the same time to let some people see themselves as others see them and thus teach them a lesson they are sadly in want of’.

To the extent to which any editorial line can be discerned, TheEye-Opener specialised in invective against Jewish businessmen; allegations of municipal corruption and commercial sharp practice; xenophobia; and, above all, innuendo-laden and cryptic accounts of alleged non-marital relationships, which were transparent attempts at blackmail.

Dickson’s principal target was Joseph Isaacs JP, a member of Dublin Corporation, president of Adelaide Road Synagogue and a successful draper who ran the Hyam & Co. store on Dame Street. Abuse was hurled at Isaacs in each of the nine issues of the paper. Described as a ‘Scotch Jew shoddy clothes merchant’ and a ‘Judas Iscariot’, it was alleged that Isaacs used sweated labour, that he allowed a Westmoreland Street property to be used as a gambling den, that he had turned against his own religion, and that he had used his position on the Corporation to push through changes in opening hours that would benefit his own business. Another Jewish target of Dickson’s was the writer Joseph Edelstein. In 1908 Edelstein wroteThe moneylender,a melodrama that attacked the prevalence of this trade in the Jewish community. TheEye-Opener claimed, however, that Edelstein himself was employed as a bookmaker’s tout, and that he had taken a sum of money from a poor woman.

‘The Black Peril’

Another fixation was what Dickson termed ‘The Black Peril’. In what may have been a reference to Indian medical students, TheEye-Opener reported that

‘Dublin has now been invaded by a new plague—namely, that known as the Black Peril. An abundant supply of coloured gentlemen are now residing in the city. We hear some rather startling tales about them.’

Most of The Eye-Opener was taken up with salacious accounts of the sexuallynefarious activities of Dubliners. Many of these accounts seem to have been purely designed to elicit a bribe for the editor. A selection of headlines gives a sense of the material: ‘Old gentleman caresses lady shop assistants’; ‘Ballsbridge married man: a warning’; ‘A married man and a typist’; ‘The Phibsboro’ flapper’; ‘Girls on the road to hell’; ‘A married man and two girls’; ‘Two students and a nurse’; and ‘French lessons’. Although it is impossible to say how many correspondents were really Dickson writing under a pseudonym, TheEye-Opener maintained a lively letters page, where Dubliners appeared to spill the beans on their neighbours’ activities. This letter, signed ‘Interested’, is typical:

‘Dear Sir, can you tell me the reason why the Ballsbridge Barrister takes so much interest in the Grass Widow residing in the vicinity of Kenilworth Park, while her husband is serving his country “somewhere in France”. I will be thankful for insertion in your badly-needed paper.’

Although The Eye-Opener avoided religious topics, Dickson made several references to an unidentified ‘Rathmines clergyman’:

‘Some of the ladies who attend a church in Rathmines, go there for other purposes besides spiritual advice. The clergyman who has charge of their souls is a bit of a nut. It amazes us to know that some of their husbands have not thought fit to wipe the the dust off the ground with the carcase of the sky pilot in question.’

Although references to corruption in Dublin Corporation abound, there is no discussion of wider constitutional issues in The Eye-Opener; Dickson was,however, loyal to the Crown and may have held conservative pro-Home Rule views.

Isaacs sues for libel

After only two months of publication, The Eye-Opener and its editor had gained an unenviable reputation. In his statement to the Bureau of Military History, the solicitor and republican activist Michael Noyk (who was himself Jewish) remembered that ‘There was at this period a very unsavoury gentleman in Dublin, a Scotsman named Dickson, who wrote a blackmailing paper called The Eye-Opener’. Unsurprisingly, in mid-April 1916 the press reported that Joseph Isaacs was suing Dickson for criminal libel. In an account of pre-trial proceedings published in the Irish Independent, counsel for Isaacs stated that the attacks on his client were of the ‘most virulent and scandalous character that ever appeared in a newspaper’, that they ‘transcend all the venom and filth I ever read’ and that ‘there is not one word of truth in any of the articles’. During these proceedings, Dickson’s motive for his pursuit of Isaacs became clearer. Isaacs revealed that Dickson was a former tenant of his in a premises on Westmoreland Street, but had been evicted for owing £40 in rent. He also alleged that Dickson had collected £10 in debts for Isaacs and failed to part with the money. Dickson, who did not offer any rebuttal, was remanded on bail and committed for trial at the next city commission. Two days later, Dickson, who might have been expected to have sought a change in career, brought out another issue of the paper:

‘Here we are, and here we mean to stay, in spite of all the obstacles that have been…placed in our way. The Eye-Opener was started for the purpose of cleansing our city of some of the pests and evils that infest it. The result…has been that we have brought down on our heads the wrath of many highly placed individuals whose conscience has pricked them to such an extent that they know not when their turn will come for the exposure of their doings to appear in our pages.’

Two days later fate, in the shape of the Easter Rising, intervened, and ‘highly placed’ Dubliners would soon have no reason to fear Dickson.

Mistaken identity

The outbreak of the Easter Rising on Monday 24 April saw Captain Bowen-Colthurst, who appears to have cracked under the strain of events, engage in an extraordinary series of killings. Bowen-Colthurst, who was later found guilty but insane after court martial, claimed that he feared an attack on Portobello Barracks. On 25 April Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, who had been seeking to prevent looting in the city, was arrested by British troops and brought to Portobello. That evening, Bowen-Colthurst assembled a raiding party, taking Sheehy-Skeffington as a hostage. The party advanced down Rathmines Road, pausing for Bowen-Colthurst to shoot an unarmed youth named James Coade. Leaving Sheehy-Skeffington under guard at Portobello Bridge (with orders that he be killed if the raiding party was fired upon), Bowen-Colthurst advanced into the city, with the intention of arresting Alderman J.J. Kelly. This was a case of mistaken identity: J.J. Kelly, a Home Ruler and former high sheriff of Dublin, opposed the Rising; his near-namesake, Alderman Tom Kelly, was a Sinn Féiner and sympathised with the rebels. It was Dickson’s misfortune to be standing outside J.J. Kelly’s tobacconist shop, which was located on the corner of Camden Street and Harrington Street, conversing with another Dublin newspaper editor, Patrick MacIntyre. MacIntyre was the editor of The Search light,a gossip sheet, and during the 1913 Lockout he had put out an anti-Larkinite journal called The Toiler. Bowen-Colthurst’s party hurled grenades at the shop, forcing Dickson and MacIntyre, both friends of Kelly’s, to take refuge within. They were presently arrested by Bowen-Colthurst and taken to Portobello.

Witnesses who spent time in the cells with Dickson claimed that he seemed unperturbed by events. Ironically, he had spent the hours before the attack on Kelly’s shop putting together a stop-press edition of The Eye-Opener which reprinted the proclamation of martial law and warned the public to conform to all military regulations. Dickson was so convinced that he would be released once this fact emergedthat he even declined the opportunity to take a wash.

At about 10 o’clock the following morning, however, Bowen-Colthurst, who had demanded that Sheehy-Skeffington, Dickson and MacIntyre be handed over to him, ordered the three men into a yard beside the guardroom. There he ordered a seven-man firing party to shoot them. According to the official report on the murders, Bowen-Colthurst had decided that shooting them was ‘the best thing to do’. Their bodies were tied up in sacks and secretly buried that night in the barrack yard.

The murders in Portobello had a peculiar coda. At the official enquiry into the events, T.M. Healy KC, who represented the families of Dickson and Sheehy-Skeffington, made a very serious allegation against Joseph Edelstein. Healy alleged that during Easter Week Edelstein had acted as a ‘spotter’ for the military and that he had played a part in Dickson’s arrest. Edelstein, who might have had reason to hate the late newspaper editor, had been in Kelly’s shop the evening it was attacked, and was in Portobello Barracks during Easter Week. A clearly very agitated Edelstein repeatedly interrupted proceedings and insisted on giving evidence. He denied all claims against him, claiming that they were based on anti-Semitic prejudice, and maintained that he was only in Portobello to arrange the transit of bread and milk for civilians. Healy, for one, believed Edelstein, telling the open court that his own statements were ‘completely wrong’, and apologised, repeatedly exclaiming, ‘I am sorry, completely sorry!’

The murder of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington had caused a sensation, partly owing to the efforts of his widow, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, to publicise the killing, and partly owing to the efforts of Major Sir Francis Vane, an officer who had served at Portobello, to bring Bowen-Colthurst to justice. The other victims, by contrast, have been largely forgotten. Sheehy-Skeffington, a kind-hearted eccentric with an aversion to violence, was fitted for martyrdom; Dickson and MacIntyre were not. Although we will probably never know what spurred Thomas Dickson to embark on a career of fraud and libel, the choices he made ensured that his death went unlamented.

Conor Morrissey is an Irish Research Council Postdoctoral Fellow in Trinity College, Dublin.

FURTHER READING

M. Gibbon, Inglorious soldier (London, 1968).

L. Levenson, With wooden sword: a portrait of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, militant pacifist (Dublin, 1983).

R. Rivlin, Jewish Ireland: a social history (Dublin, 2011).

Read More:

Joseph Edelstein