The 1841 census— do the numbers add up?

Published in Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2015), Volume 23

‘Their huts are not like the houses of men and yet out of them troop flocks of children, healthy and fresh as roses.’ Frenchman De Latocnaye’s observation in the 1790s is borne out by the sturdiness of the children in this 1850 painting, An Irish Eviction, by Frederick Goodall. (Leicester Museum & Art Gallery)

The first official decennial census of the population was taken in 1821, and thereafter every ten years until 1911. It is accepted that the census figure for 1871 is the first return that can be considered as reasonably reliable owing to the compulsory registration of births from 1863 onwards. The accuracy of the 1841 census returns attracted particular criticism and it is premised that the decline in population between 1846 and 1871 may have been grossly under-quantified. There is no doubt that by any reckoning the Great Famine took a ter-rible toll on the population.

1741—bliain an áir

The country’s population had been relatively stable during the early decades of the eighteenth century, and then came the ‘Great Frost’ of 1740. Between December 1739 and September 1741 Europe was afflicted by extraordinary climatic changes. In Ireland, from early January to the end of February 1740 temperatures fell to as low as –12°C. The frost ruined the potato crop and a drought in April destroyed the grain crop. The return in September, October and November of the arctic conditions of the early part of the year caused the death of many thousands of animals. The general population, having suffered catastrophic repercussions from severe weather, lack of food and the virulence of epidemics, were now in dire circumstances. Newspaper articles from December 1740 to August 1741 relate stories of the prevalence of fevers and diseases in different parts of the country. Four distinct diseases are identified: smallpox, ‘bloody flux’ (dysentery), malignant or spotted fever (typhus) and intermittent fever (relapsing fever). Some famine relief measures were introduced, but these were voluntary and too small in scale. Out of an estimated population of 2.4 million, it is claimed that between 310,000 and 480,000 people may have perished. Because of the devastation suffered, 1741 was labelled bliain an áir (‘the year of the slaughter’).

Population recovery

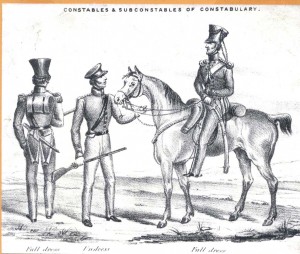

Irish Constabulary c. 1840s. In the 1841 census members of the constabulary were delegated to do the job of enumerator. But were they the best choice? (Garda Museum and Archives)

Following this tragedy, the population of Ireland recovered and increased rapidly year on year to reach the incredible figure of 8,199,853 by 1841. This significant demographic change occurred thanks to the confluence of a number of favourable circumstances: a better diet, a decline in the outbreaks of fever, and more frequent and younger marriages. Young couples were encouraged to marry early by these favourable circumstances—a sod cabin and a small patch of land on which to grow potatoes was all that was required. Girls married at sixteen, boys at seventeen or eighteen. Asked why the Irish married so young, the Catholic bishop of Raphoe told the Irish Poor Enquiry in 1835: ‘They cannot be worse off than they are and . . . they may help each other’.

Irish women were exceptionally fertile, as recorded by Arthur Young when he wrote: ‘. . . for twelve years 19 in 20 of them breed every second year. Vive la pomme de terre!’ The Frenchman De Latocnaye wrote:

‘Their huts are not like the houses of men and yet out of them troop flocks of children, healthy and fresh as roses. Their state can be observed all the easier, since they are often as naked as the hand, and play in front of the cabins with no clothing but what Nature has given them . . . They live on potatoes, and they have for that edible (which is all in all to them) a singular respect, attributing to it all that happens to them. I asked a peasant who had a dozen pretty children, “How is it that your countrymen have so many and so healthy children?” “It’s the praties, sir”, he replied . . . One finds numerous schools in the hedges—always for the reason I have indicated already. It is a mistake to think the peasant of this country so ignorant or stupid. Misery, it is true, does stupefy him and make him indifferent.’

Joseph Lee comments: ‘for the peasant family in pre-famine Ireland, children were welcomed and considered a “Godsend”’. Children, no doubt, provided insurance for their parents against destitution in old age.

In 1831 the government established a national school system in Ireland under the control of the Commissioners of National Education. The second national census was taken that year and recorded a population of 7,767,401. From that time the commissioners recorded an estimated population for every year in between the official decennial census years. These statistics are recorded in The History of the Vote for Public (Primary) Education, Ireland, 1 January 1831 to 1 March 1895.

The enumerators

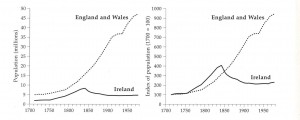

From ‘The vanishing Irish: Ireland’s population from the Great Famine to the Great War’ by Timothy Guinnane (HI 5.2, Summer 1997, p. 33).

On previous occasions the enumerators of the census had been literate local people hired to carry out the project by visiting people in their homes. In 1841 members of the Irish Constabulary, ‘a highly disciplined body of men’, were delegated to do the job. They were considered superior to the previous enumerators in that they were an independent force, responsible to their officers for their fidelity and integrity, and could be relied on to guarantee an impartial return. In addition, their numbers and distribution would provide a facility for simultaneous enumeration.

The population lived mainly in the rural areas, and enormous logistical and geographical obstacles had to be overcome to ensure an accurate census. Much time, local knowledge and courage was required to penetrate the bogs, climb into wild glens and up mountains, and track down the communities of evicted and unemployed peasantry who existed in caves and sod huts. The choice of the local constable as enumerator must have created its own problems. His visits to collect information would not have been welcomed in many abodes. The peasantry would generally have had little respect for authority and a natural reluctance to be registered. Furthermore, they would have recognised that by being registered they were more likely to be made answerable to the laws of the land and liable to the imposition of taxes.

Despite this census being considered more reliable than the previous one, a number of serious reservations were expressed regarding the accuracy of the figures returned in its report. Claims were made that the actual population figure was seriously under-quantified. The census commissioners analysed the returns for the previous censuses:

1821 6,801,827

1831 7,767,401

1841 8,175,124

The population had increased by 14.2% during the decade 1821–31, but by only 5.25% for 1831–41. Many proposals were put forward to explain this large difference in the population increase during these two decades. Among them were:

• that the accuracy of these percentages depends upon the relative accuracy of the several censuses of 1821, 1831 and 1841;

• that the 1821 census, being the first one, was probably affected by less perfect machinery;

• that the census of 1831 was taken at different times in different places, extending over a considerable period;

• that the army serving in Ireland, together with their wives and family, were omitted as they did not strictly belong to the population of the country;

• that large numbers had emigrated to seek employment in the manufactories in England and Scotland.

Having considered the matter fully, the census commissioners issued a report stating that, in their opinion, the population of 1831 had an undiminished rate of increase between 1831 and 1841 and that the population returned for 1841 should have been 9,018,799. It was noted that the 1841 census for Scotland showed an increase of 10.8% in the population between 1831 and 1841.

Paradoxically, whilst accepting that the rate of increase had been undiminished, the official parliamentary census report of 1841 still maintained that 8,175,124 was the correct figure. It was argued that the census commissioners had not given sufficient weight to the consideration that the censuses of 1821 and 1831 were both inaccurate, the former by a deficiency and the latter by an excess.

A Board of Works inspection officer in County Clare tested the population figures that had been officially returned for his district and found the actual population to be one third greater than had been recorded. Writing to the secretary of the Board of Works, he stated that the census of 1841 was ‘pronounced universally to be no fair criterion of the present population’. Census officers engaged in famine relief work estimated that the population was as much as 25% greater than the figure given in the official returns. They reported that ‘Landlords distributing relief were horrified to find when providing, as they imagined, for 60 persons, to find more than 400 start from the ground’.

Summation

Gustave de Beaumont—in 1839 the French traveller had written that ‘he found in Ireland the extreme of human misery, worse than the Negro in his chains’.

Two options may be considered when assessing the premise that the population decline in Ireland between 1846 and 1871 may have been grossly under-quantified by over-reliance on the (flawed) 1841 census returns.

Option 1

The Commissioners of Education recorded an estimated population of 8,287,848 for the year 1846, only a 1.38% increase on the 1841 census figure over a five-year period. The official census figure for 1871 was 5,412,377; the registration of births had been made compulsory in 1863, suggesting that this figure is reliable. Accepting both population figures as correct, then the drop in population in the 25 years between 1846 and 1871 would have been 2,875,471.

Option 2

If it is accepted that the population was under-quantified in the 1841 report and that the census commissioners’ estimated figure is correct, then the population was well in excess of nine million when the Famine struck in 1845.

The census commissioners postulated that the correct 1841 figure should have been 9,018,799, a 10.3% difference. If that figure is accepted as correct, then the Commissioners of Education’s figure for 1846 should have been 9,141,496, an increase of only 1.38%, their projected estimated increase. Accepting these revised figures as correct, the drop in population, between the estimated high point in 1846 and the official figure in 1871, would be 3,729,119.

Comment

While reservations have been recorded regarding the 1841 census figure, it is unquestionable that accurate statistics for the period 1846–63 are not available. Recording of births and deaths by both church and state was fragmentary and incomplete. Records of events during the Famine provide accounts of considerable numbers of men, women and children being buried in mass graves. Many more just lay where they died, not counted and not buried.

Woodham-Smith states that ‘in the short five years more than a million died of starvation and of the diseases which accompany malnutrition’. Joseph Lee states that about 10% of the population died from hunger and disease between 1845 and 1851. Over the 55-year period from 1846 to 1901—a period of Famine deaths, a declining marriage rate, a declining birth rate, a reduction in the average size of families and emigration—the population declined by between 3,829,073 and 4,560,024.

Michael Moroney is a former General Treasurer/Deputy General Secretary of the Irish National Teachers Organization.

Read More:The 1841 census

Further reading

G. de Beaumont, Ireland: social, political and religious, vol. 1 (London, 1839).

D. Dickson, Arctic Ireland (Dublin, 1997).

J. Lee, The modernisation of Irish society, 1848–1918 (Dublin, 1973).

C. Woodham-Smith, The Great Hunger (London, 1962).