Armagh Conference to Reflect on Northern Voices of the Irish Revolution

Published in Issue 5 (September/October 2015), News, Volume 23

A group supporting IRA hunger strikers in Crumlin Road Jail, Belfast, 1920. Patrick Diamond (back row, second from the right) from south Derry was an O’Kane interviewee. (Cardinal Ó Fiaich Library & Archive)

A newly digitalised collection of 50-odd interviews with Ulster veterans of the Irish Volunteers and pre-Truce IRA, carried out by Fr Louis O’Kane some 50 years later, provides the inspiration for a one-day conference in Armagh in November 2015—‘Reflections on the Revolution in Ulster: the Irish Volunteer movement in the North, 1913–23’.

Northern participants’ reluctance to have their memories recorded was understandable. Embitterment about partition and abandonment by the Irish Free State, combined with close scrutiny from the unionist authorities, made them instinctively wary of the motives of authorities. After 1954, contemporary events spelt the end of the Bureau of Military History’s collection of testimonies from northern residents.

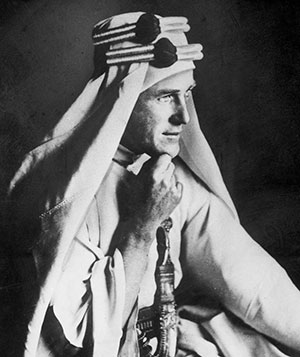

Veteran voices stayed muted until Fr Louis O’Kane came along. His first historical venture was Lower Killevy, Ireland: outlines of their history (1955), which purposely emphasised the local narrative as a microcosm of the national. His primary interest, however, lay in the revolutionary period, to which he was a teenage witness in his native Magherafelt. He initiated an ambitious oral history project that perhaps no one else could undertake: to interview old Irish Volunteers and IRA veterans all around Ulster. Having served in parishes all over the archdiocese—in south Derry, east Tyrone, south Armagh and Louth—he had built up a network of contacts throughout. His friendly manner, his contemporary status with the interview subjects, his republican sympathies and above all his status as a priest won the trust of veterans that their taped words would be safe with him.

In 1963, while working in Loughgilly parish in south Armagh, O’Kane began his project in earnest. Using an early Grundig portable tape-recorder, he interviewed local men such as Eddie Boyle and John ‘Ned’ Quinn, as well as Dublin-based former IRB centres Séamus Dobbyn and Liam Gaynor (both Belfast natives). He would later move on to prominent Armagh men John McCoy and Charles McGleenan, and several Louth men from the IRA’s Fourth Northern Division.

From 1966 to 1973 O’Kane stepped up the pace of his project, recording more frequent interviews, despite an increased workload as parish priest of Aghaloo, Co. Tyrone. He focused now on foot soldiers of the IRA’s Second Northern Division in Tyrone and his own south Derry especially. Among these were Major Tom Morris, a Great War veteran who returned with guns to arm the Bellagherty company; Cumann na mBan member Alice McSloy; and Rory Graham, a Protestant from east Belfast who describes feeling like ‘a sort of a white blackbird’ upon joining the Volunteers in 1917. During this period O’Kane travelled further, to Donegal to record Dr J.P. McGinley, and around Connacht to meet Ulster exiles in Sligo, Roscommon and Galway. Several southern-based interviewees were former Garda or Irish army officers who had fled the north in 1922. Some of their disclosures reveal as much about the intricacies and intrigues of life in the Free State as of the preceding period.

In 1968 O’Kane interviewed one of his most notable subjects, Kathleen Clarke, while she was visiting from England. Although not from Ulster, Clarke’s crisply spoken words are certainly of relevance to the province, not least when she lambasts Eoin MacNeill’s ‘treachery’ and Roger Casement’s role as a pensioned knight of the British Empire who ‘knew very little about Ireland’ and ‘went off to Germany and started things that the revolutionary group here didn’t want’.

The onset of the ‘Troubles’ in 1969 led O’Kane to extend the scope of his collection. Every morning, noon and evening for the next four years he recorded RTÉ and BBC radio bulletins on tapes labelled ‘News from the Sick Counties’. O’Kane also became more careful about the security of his recorded interviews, moving them from his parochial house in Aughnacloy to a trunk in another priest’s home in Monaghan. O’Kane was still busy recording and collecting when he died quite suddenly in August 1973. That trunk, containing in excess of 200 old reel-to-reel tapes, plus a miscellany of revolutionary documents, photographs and artefacts, lay in a convent in Magherafelt for most of two decades. It was then transferred to Armagh, residing in Ara Coeli, the archbishop’s house, until the Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Memorial Library and Archive opened in 1999.

For some 40 years the collection was largely unknown beyond relatives of the interviewees, and otherwise only a few well-informed and determined academics got to listen to the fragile old reels. The Department of Foreign Affairs’ provision of a €20,000 grant in 2013 enabled the digitalisation of all the recordings and the opening up of access to users of the archive. The current Irish Volunteers Centenary Project, assisted by the Heritage Lottery Fund, will deliver outreach events in O’Kane’s former parishes in counties Tyrone, Armagh, Derry and Louth between autumn 2015 and spring 2016.

‘Reflections on the Revolution in Ulster’, Ó Fiaich Library and Archive, Armagh, Saturday 14 November 2015, www.ofiaich.ie, 048-37522981.

Dónal McAnallen is Outreach Officer with the Cardinal Ó Fiaich Library and Archive, Armagh.