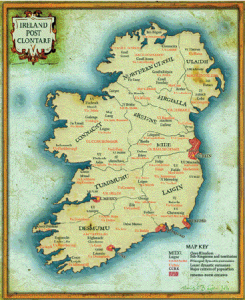

Life after Brian: the high-kingship

Published in Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2014), Volume 22

The crowned head of Brian Boru on the Chapel Royal, Dublin Castle. While the concept of the kingship of Ireland was old, it is unclear what it entailed.

A fundamental problem with the so-called kingship of Ireland after Brian (or indeed during Brian’s own reign and before) is that, while the concept was certainly old, it is unclear what it entailed. As early as the seventh century, kings of Cenél Conaill (County Donegal) were recorded in the annals as kings of Ireland, but such pretensions would have been laughed at by contemporaries in Munster; their title was influenced by the recording of these annals in the monastery of Iona, whose abbots were drawn from among Cenél Conaill themselves. It was only in the middle of the ninth century—when Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid, the Southern Uí Néill king of Tara, took hostages from Munster—that anyone could claim to be king of Ireland in a meaningful sense. Despite the an-tiquity of the idea, the kingship of Ireland was not an institution, and while some men were occasionally labelled ‘king of Ireland’ it does not follow that they succeeded to an office, or that they enjoyed the same rights and responsibilities as earlier/later kings with similar titles. In many respects the kingship of Ireland was not simply won but had to be created afresh by each claimant, and we need to be mindful of both its nebulous nature and the idiosyncrasies of the men who claimed it.

What’s in a name?

An important and well-known term used in connection with kings of Ireland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries is ardrí (‘high-king’), yet it was not confined solely to the men who claimed the kingship of Ireland. In the annals ardrí was also used for kings of Airgialla (Armagh–Monaghan–Louth), Osraige (Kilkenny) and even individual divisions of the Eóganachta (who as a whole were playing second fiddle to Dál Cais in Munster anyway). A further terminological issue relates to whether kingship was envisaged as relating to a people or to a territory—was the high-king a king of Ireland or a king of the Irish? In the account of the Battle of Clontarf in the Annals of Ulster, Brian was both ‘king of Ireland’ and ‘high king of the Irish of Ireland’, whereas in the corresponding entry in the Annals of Inisfallen (from Munster) he is not accorded any title at all.

An important and well-known term used in connection with kings of Ireland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries is ardrí (‘high-king’), yet it was not confined solely to the men who claimed the kingship of Ireland. In the annals ardrí was also used for kings of Airgialla (Armagh–Monaghan–Louth), Osraige (Kilkenny) and even individual divisions of the Eóganachta (who as a whole were playing second fiddle to Dál Cais in Munster anyway). A further terminological issue relates to whether kingship was envisaged as relating to a people or to a territory—was the high-king a king of Ireland or a king of the Irish? In the account of the Battle of Clontarf in the Annals of Ulster, Brian was both ‘king of Ireland’ and ‘high king of the Irish of Ireland’, whereas in the corresponding entry in the Annals of Inisfallen (from Munster) he is not accorded any title at all.

In addition, the popular notion that the king of Tara was king of Ireland was promoted by medieval authors who sought to dress an important earlier kingship in later clothes. Interestingly, although they attempted to equate the kingship of Ireland with that of Tara, the terms ‘king of Tara’ and ‘high-king’ are rarely used in the same breath. The kingship of Tara was certainly significant from the earliest period of recorded history, but it was never a ‘national kingship’, even if individual kings of Tara (such as Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid) did strive toward Ireland-wide dominance. Indeed, it is an irony of Irish history that just as an effective kingship of Ireland was becoming an achievable goal the kingship of Tara was being overshadowed; the last king of Tara to be recognised as king of Ireland was Brian’s old sparring partner, Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill (d. 1022). Although the kingship of Tara had alternated between the northern and southern branches of the Uí Néill previously, after Máel Sechnaill the kings of Tara were drawn exclusively from his Southern Uí Néill descendants. Nonetheless, the Northern Uí Néill did not seem particularly bothered at the loss of this title; they emerged as the more powerful of the two groups. Even the increasingly hard-pressed Southern Uí Néill kings were as inclined to call themselves kings of Mide as kings of Tara—the title was circling the drain even faster than its holders.

Identifying kings of Ireland

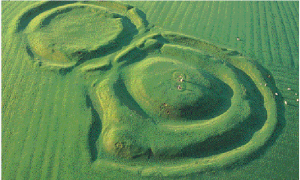

The Hill of Tara—the popular notion that the king of Tara was king of Ireland was promoted by medieval authors who sought to dress an important earlier kingship in later clothes. (Con Brogan)

Military success was the backbone of any claim to the kingship, and no man was ‘born into the purple’; circumstances, ability and chance all played their parts for each aspirant. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, contemporaries appear to have recognised a handful of men as kings of Ireland, although particular sources might claim (or exclude) individual kings, depending on either bias or perception. For example, the Annals of Tigernach commemorated Tairdelbach Ua Conchobair as ‘king of all Ireland, and the Augustus of the west of Europe’, but the Annals of Ulster simply recognised him as ‘high-king of Connacht’. Both sources were actually complementary in these obits, but the Annals of Ulster may simply have been recognising that the last years of Tairdelbach’s life had seen his eclipse by a rival claimant to the kingship of Ireland, Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn.

For those claimants who did not enjoy unopposed success, it has become a commonplace to suggest that many of them held the title ‘king of Ireland with opposition’ (rí Érenn co fressabra). F.J. Byrne has suggested that the concept of ‘king of Ireland with opposition’ was probably an invention of Áed Mac Crimthainn, abbot of Terryglass (Co. Tipperary) during the twelfth century, in order to justify claims that Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó of Laigin (Leinster) had earlier held the kingship of Ireland (which is not recorded in contemporary annals), and also the ambitions of Áed’s patron, Diarmait Mac Murchada.

Warriors on the edge of the Stowe Missal shrine or cover. Brian’s son and successor, Donnchad, was never generally acknowledged as king of Ireland but was recorded as such on the missal’s shrine. (NMI)

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries the top tier of Irish kingship was extremely restricted; only Uí Briain of Munster, Uí Conchobair of Connacht and Meic Lochlainn of the North (Tyrone) were sufficiently powerful to be recognised as kings of Ireland. Below them was a second tier of kings, who had to be either wooed or sufficiently cowed into submission if a budding king of Ireland were to realise his potential. Indeed, it was the revolt of one such powerful vassal, Donnchad Ua Cerbaill of Airgialla, which precipitated the downfall of the reigning Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn in the 1160s. This lesson was not lost on his successor, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair (son of Tairdelbach), who executed hostages upon the threat of revolt by his own principal subordinate, Tigernán Ua Ruairc of Bréifne.

Kings of Ireland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries

Above: James VI of Scotland—there would not be another king of Ireland who claimed Gaelic descent until James became ruler of the three kingdoms in 1603. (Scottish Portrait Gallery)

After Brian’s death, the man who stood to gain most was the king of Tara, Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill. He attempted to regain the dominant position he had enjoyed prior to Brian’s rise, but time was not on his side. Already an old man, he campaigned to the end, fighting his last battle only a month before he died. Máel Sechnaill met his end peacefully in 1022 and almost all sources accord him some variant of the title ‘king of Ireland’. One of his chief rivals was Brian’s son and successor, Donnchad, who despite considerable achievements was never generally acknowledged as king of Ireland, although he certainly had ambitions in that direction and was recorded as such on the shrine of the Stowe Missal. A text in the twelfth-century Book of Leinster, entitled Do fhlaithesaib ocus amseraib Hérend iar creitim (‘On the reigns and times of Ireland after [the introduction of the] faith’), suggests that Máel Sechnaill’s death was followed by a ‘joint rule’ in Ireland for the space of 42/50 years—that is to say, no single king distinguished himself enough to be entitled king of Ireland during that period.

Later Dál Cais kings of Ireland

Tairdelbach ua Briain (d. 1086; Brian’s grandson) and his son Muirchertach (d. 1119) dominated Irish politics for large parts of the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. Tairdelbach became king after a long campaign against his uncle, Donnchad, who died on pilgrimage in Rome in 1064. Tairdelbach was an arch-manipulator, excelling at the stratagem of divide and rule. He sought to turn the threat posed by the Hiberno-Scandinavian towns into an advantage by installing his sons as rulers of Dublin and Waterford, and while he never extended his dominance over the north of Ireland, external correspondents such as Pope Gregory VII and Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury addressed him as king of Ireland. Tairdelbach’s son, Muirchertach, continued many of his father’s policies, including supporting so-called church reform and manipulating the Hiberno-Scandinavian towns. Like his father, Muirchertach too failed to dominate the north, finding himself thwarted by Domnall ua Lochlainn (who with less justification was credited with being king of Ireland in some of his obits in 1121). Muirchertach’s kingship was characterised by its outward orientation; his interests in the greater North Atlantic world of the early twelfth century may be seen through events as disparate as his alliance with King Magnus Barelegs of Norway and his receipt of a gift of a camel from Edgar, king of Scots!

Tairdelbach Ua Conchobair

Diarmait Mac Murchada, king of Leinster, from the margins of Topographia Hiberniae by Gerald of Wales. Mac Lochlainn’s chief ally, his treatment by Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair caused him to seek aid from the Norman world and set in train the most pivotal event in Irish history since the coming of Christianity—the English invasion. (NLI)

Tairdelbach Ua Conchobair (d. 1156) was a man characterised by enormous energy and exerted himself with the vitality that became a man of ambition. He owed his kingship of Connacht to a revolt against his own brother in 1106, in which he sought and received the support of the Uí Briain, whom he was later to turn against. Spirited military campaigning, cunning and brutality were the hallmarks of his rule. Tairdelbach defended Connacht through innovative fortification-building, set his sons as puppet kings over other kingdoms, broke the power of the Uí Briain in battle and slaughtered the hostages of rebellious subordinates. He responded to slights with swift and devastating effectiveness, gouging out the eyes of one of his own sons; and when another son was killed by the men of Mide, he inflicted such slaughter upon them that one annalist mournfully recorded that it ‘was like the Day of Judgement’. His ambitions, as we have seen, were thwarted in his later years by the rise of Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, but his career saw Connacht metamorphose from a provincial back-water into a centre of Ireland-wide power.

Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn

Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn (d. 1166) of the Northern Uí Néill appears to have appreciated that to be a king one had to be seen as a king. His collaboration in the property acquisition and construct-ion plans of major churches allowed him to parade his magnificence, munificence and ability to exercise power in other kingdoms; with some justification his charter to the newly established Cistercian abbey at Newry declared him rex totius Hiberniae (‘king of all Ireland’). His downfall was entirely of his own creation. In 1166 he blinded Eochaid Mac Duinn Sléibe, king of Ulaid (Ulster), which caused his foremost subordinates to rebel. The revolt was brilliantly manipulated by Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair (son of Tairdelbach) and Mac Lochlainn died in a minor skirmish, with contemporary sources noting that it was a rather pathetic end for one who had been so powerful.

Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair

A brilliant series of political and military manoeuvres saw Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair (d. 1198) climb to the top of the greasy pole at Mac Lochlainn’s expense, but ultimately they were responsible for his own downfall. His treatment of Mac Lochlainn’s chief ally, Diarmait Mac Murchada of Laigin, caused the latter to seek aid from the Norman world and set in train the most pivotal event in Irish history since the coming of Christianity—the English invasion. Ruaidrí responded to the newcomers with both force and diplomacy, and while his failure to dislodge the invaders from Dublin marked a turning point in his fortunes, he nonetheless came extremely close to succeeding. It has been generally accepted that Ruaidrí’s kingship effectively ended with Henry II’s expedition to Ireland (1171–2), but this was not immediately apparent. The Treaty of Windsor (1175) with Henry II theoretically gave Ruaidrí a free hand in much of Ireland (although it proved ineffective), and in 1180 he arranged for his nephew to be transferred from the bishopric of Elphin to that of Armagh; presentment to the primatial see was a strong indication of his continued desire to act as a national king. Ruaidrí’s death notice in the Annals of Inisfallen was glossed by a later writer saying ‘he had held the kingship of Ireland for a period’—a reasonable summary of his career and an indication that times had changed. With the exception of a short-lived attempt at glory by Brian Ua Néill in the middle of the thirteenth century, there would not be another king of Ireland who claimed Gaelic descent until James VI of Scotland became ruler of the three kingdoms in 1603.

Denis Casey is a post-doctoral researcher for the Emperor of the Irish exhibition on Brian Boru at Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

F.J. Byrne, ‘Ireland and her neighbours, c. 1014–c. 1072’ and M.T. Flanagan, ‘High-kings with opposition, 1072–1166’, in Dáibhí Ó Cróinín (ed.), A New History of Ireland 1: Prehistoric and Early Ireland (Oxford, 2005).