The Irish are violent—official (secret)

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2014), Volume 22

Dealing with the ‘violent’ Irish—British Army photograph of a riot in the Bogside, Derry, at Easter 1981. (Imperial War Museum)

‘The history of Northern Ireland in the last four hundred years has been the history of a divided society, where an habitual belief in the concept of violence as a first rather than a last resort in political and social conflict and the corresponding failure of political settlement . . . have combined to present successive British governments with a uniquely difficult range of problems. The enlightened assumption that political and religious divisions within society would be eliminated and give way automatically to social harmony . . . has been constantly imperilled by the antagonistic emotional factor.’

So there we have it: the (Northern) Irish are naturally violent and emotionally antagonistic. And, good heavens, this has made things annoyingly troublesome for the British.

These opening paragraphs are from Claire Marson’s History of Northern Ireland from 1650. This, however, can only be located and read at the UK’s National Archives in Kew, London. But that relative obscurity does not make it without influence: the history was produced by a London branch of the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) of the British government, the author was an employee of that organisation, and her work, written in 1976–7, was proclaimed to be an ‘official history’ by leading civil servants of the NIO. All of this gives it influence and makes the history of this history a story worth telling.

Revd Ian Paisley during the second loyalist strike, one of several events in 1977 that allowed for a certain pessimism of interpretation. (Victor Patterson)

There is no doubt that a consideration of what was happening in Northern Ireland in 1977 does allow for a certain pessimism of interpretation, evident in the above quotation. Attempts to build power-sharing administrations had floundered; between 14,000 and 15,000 British troops were stationed in Belfast, Derry, South Armagh and elsewhere; deaths in the conflict were averaging one in every three days; a hunger strike by Republican prisoners had taken place; and the second Loyalist workers’ strike had occurred. So it is hardly surprising that British civil servants would welcome an explanation of what all this mayhem was about. Accordingly, they commissioned Claire Marson of the NIO’s Division 4 to write a history. After a first draft, the final printed document was produced in early 1977. This was not for public consumption, but copies were dispatched to prominent civil servants in the NIO in both London and Belfast, as well as, as we shall see, to leading politicians in the British administration. It appeared in book form in December 1977.

Potted history

A history of Northern Ireland from 1650 is approximately 35,000 words long, typeset in 33 pages. Only six pages deal with the period before 1900 and just half a page is afforded to 1900–1968. The history ends in 1976, although there were plans to add to it year by year and a subsequent year’s account was later written. When it was first drafted, one of Marson’s superiors described it as ‘a fascinating document and a very creditable one’. Others might—and, indeed, did—dispute this.

It soon becomes apparent that the author is looking at Ireland through an exclusively British prism. This is hardly surprising: she was a British civil servant whose job it was to evaluate from the point of view of her historic and contemporary political establishment. This she did. For example:

‘Ever since the Norman Conquest Catholic [sic] Ireland has been unstable and has proved a permanent source of anxiety for successive British monarchs, who feared among other things the possibility of Ireland being used as a “back door” to England by England’s enemies.’

Or:

‘During the mid-seventeenth century, determined efforts were again made to subjugate the native Irish who were perceived as a threat to Britain.’

Few would argue with these statements (apart from the anachronistic reference to ‘Catholic Ireland’). The problem is that they are not preceded or accompanied by any attempt to explain what lay behind Irish instability since the Normans or why the seventeenth-century Irish were revolting to the extent that they were in need of subjugation. No, it is the effect of such behaviour on England that is important, not the reason for it in the first place. Similarly, when Marson describes the Act of Union she suggests that the British were gracefully conceding to an Irish demand, albeit one that had been made nearly a century before:

‘By 1798 the British government had decided on the creation of a legislative union . . . Ninety years earlier the Irish Parliament itself had asked for such a union, only to have the petition rejected in England, but by the middle of the eighteenth century there were widespread fears in England that the two kingdoms were growing apart and the only way to prevent this was complete amalgamation.’

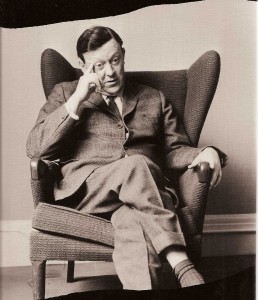

Conor Cruise O’Brien—his States of Ireland (1972) was quoted directly by Marson. (Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Put this way, the Act of Union is presented as a benign concession to the Irish, an interpretation that allows the author to overlook and not mention the corruption by which it was achieved or the fear of an Irish/French alliance, which the more conventional histories suggest was one of the principal motivations. This approach of a responsive British administration is one feature of Marson’s work, but the most persistent theme is that contained in the opening paragraph quoted above—the violence of the Irish and their leaders. Thus she writes how the British were reformist enough to pass Catholic Emancipation, but also states that O’Connell was ‘aggressive by nature’. Or, on the defeat of Gladstone’s first Home Rule Bill, we are reminded that Parnell ‘had just spent some time in Kilmainham gaol for violent speech making’ and that the Phoenix Park murders ‘caused a sweep of anti-Irish feeling’. These two factors are the only ones cited to explain the defeat in 1886 of Gladstone’s Home Rule bill and the subsequent defeat of Gladstone at the general election.

The tendency to suggest that it was the violence of the rebellious Irish that brought trouble on their heads is again apparent when Marson deals with Belfast’s anti-Catholic pogroms following partition. We are told: ‘The IRA was particularly active in provoking anti-Catholic rioting in Northern Ireland in 1920 and 1921 in which thousands of Catholic families were driven from their homes’. Again, they brought it on themselves.

Sources

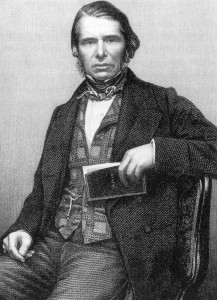

Charles Trevelyan—‘The first year of the Famine was made easier by the sensible attitudes and hard work of Peel and a British civil servant, Charles Trevelyan.’ (Multitext)

The 1970s

The one author that Marson quotes directly is Conor Cruise O’Brien and his States of Ireland (1972) on the attitude of Northern Irish Catholics to the presence of the British Army in the early 1970s. The Catholics, says O’Brien/Marson, ‘tended to object to the presence of the British Army in principle, but accepted the need for it in practice’, a remark that many would say has rather more style than substance. Whatever, it is the context of this period, when the NIO produced its history, that gives it a particular relevance and lifts it above an opportunity to have a few swipes at eccentric opinions. Thus the introduction of internment is explained in this way:

‘After one of many Falls Road searches . . . as far as Catholics were concerned it seemed less natural they should feel approval of the British Army. The PIRA exploited this . . . their campaign of violence resulted in death and destruction

. . . It had become impossible to obtain evidence to combat effectively the campaign of violence

. . . Accordingly, following consulta-tion with the Westminster government, Mr Faulkner’s government introduced internment.’

First, it was the British Army-imposed Falls curfew of 3–5 July 1970, during which the Army shot four civilians, that decisively turned that army into a familiar colonial enemy for many Catholics, and to describe this as ‘one of many searches’ is a gross understatement. Second, the introduction of internment was not motivated by security concerns but by political ones, especially the British government’s decision to prop up Brian Faulkner, and this, as the Saville Enquiry has shown, was well known to senior British civil servants at the time. Third, it was not just that the UK government was ‘consulted’ about internment; it was a fully fledged partner in its introduction. Again what we see here is an interpretation that minimises British responsibility and maximises that of the natives. Similarly, when dealing with Bloody Sunday, the first sentence begins ‘An illegal march . . .’ and goes on to replay the familiar arguments that the soldiers were returning fire. Such, of course, was what the British argued at the time: illegal marchers and Irish gunmen—all their fault.

Official British reaction

‘A British soldier checks distant activity . . . during a patrol in the centre of Newry’—official British Army photograph, undated but probably the 1980s. (Imperial War Museum)

Seaman’s objections were contested by the head of Section 4, Austin Wilson, who responded: ‘We do not regard the document as perfect . . . But I do not think that, at this stage, it needs a major revision’. Wilson did, however, suggest that security classification for the History should be raised to ‘restricted’. It is not clear whether this occurred—the file in the National Archives is merely stamped ‘confidential’—but certainly it was subject to the 30 years rule of secrecy.

Wilson also said that the purpose of the work was principally as a briefing for civil servants new to the NIO. The distribution list suggests that this was not the whole truth, because copies were also sent to prominent civil servants and to the offices of three government ministers, including the Secretary of State, Roy Mason, who borrowed a draft copy over Christmas 1976 and then asked for his own personal copy: he was sent two. Now, this is not the place to enter into a discussion on the merits or otherwise of Roy Mason’s period in office. What can be suggested is that it is difficult to see his views and those in the History conflicting. More generally, it is worth observing that while both unionist and nationalist communities in Ireland are often accused of creating and believing their own historical myths, so too did the British, as indeed has also been said before. But that their myths were embedded to the extent that they became ‘official’ and part of a briefing for their civil servants and government ministers may explain a good deal.

Geoffrey Bell is a writer, based in London.

Further reading

J.C. Beckett, The making of modern Ireland (London, 1966).

Division 4 (Northern Ireland Office), A history of Northern Ireland from 1650, (UK) National Archives, CJ4/2994.1975–1978.

R.K. Webb, Modern England: from the eighteenth century to the present (New York, 1968).