‘As happy as seven kings’: Cycling in Nineteenth-Century Ireland

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2014), Volume 22

Brian Griffin assesses the revolutionary impact of the bicycle on the lives of Irish people, particularly women, by the 1890s.

In November 1897 the editor of the Irish Wheelman, J.C. Percy, surveying recent developments in the cycling trade in Ireland, declared that ‘Cycling has now found its level, which happily is a very high one. It is no longer a fad or a fancy, but an established factor in modern everyday life… The army of riders is increasing with constant and steady growth, and will continue to enrol in its numbers members of every age, sex, and rank.’

The newspaper’s female columnist, ‘Portia’, commented that ‘The day will come when we shall wonder how we ever existed before the advent of the cycle. Doctors who are still shy about visiting their patients by such locomotive means will do so as an ordinary occurrence. Governesses will arrive at their pupils’ houses on their machines; men and women will pay their calls as a matter of course on their bicycles, while by this means even the frock-coated clergyman will visit his parishioners.’

The revolutionary changes that ‘Portia’ predicted were already occurring in much of Ireland even as she penned her column. Indeed, such was the pace at which cycling’s popularity was growing that in July 1898 the Irish Tourist published an imaginative piece, ‘Dublin fifty years hence’, in which the author speculated on how the enthusiasm for cycling would affect the capital city if it persisted into the future. In the Dublin of c. 1950, cycling ‘scorchers’ and anybody who deliberately sang ‘Daisy Bell’ would be ‘mercilessly shot down by the nearest passer-by’, while the Liffey between the Custom House and Capel Street would be pumped dry and the riverbed transformed into a splendid concrete cycling track. While cycling obviously never developed to these absurd levels, by the late 1890s it was nevertheless no longer viewed as an unusual ‘fad’ or ‘fancy’ but had become a commonplace activity throughout Ireland.

The ‘ordinary’ or ‘penny-farthing’

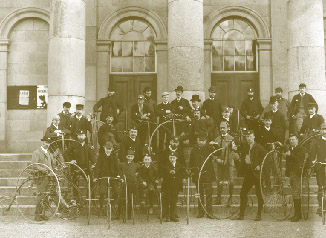

While cycling in various guises engaged the interest of small numbers of Irishmen in the 50 years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the introduction of the first pedal-driven bicycle—the velocipede or ‘boneshaker’—in the late 1860s led to a significant surge of interest in the pastime. The boneshaker, a machine consisting of two wheels and which was propelled by pedals on the front wheel, frequently made for an uncomfortable ride on Ireland’s poorly constructed roads, as its nickname suggests; nevertheless, riders were able to travel further and at greater speed on it than they could on wooden tricycles and quadricycles, and the boneshaker quickly became the most popular form of cycle in Ireland. Its popularity was short-lived, however, as it was superseded in the early 1870s by the high-wheeled ‘ordinary’ bicycle (often nicknamed the ‘penny-farthing’ by non-cyclists); like the boneshaker, the ordinary was propelled by pedals on the front wheel, but one could travel much further and at greater speed on the ordinary than one could on the boneshaker, and with less physical effort. Riders of ordinaries were often pitched head first over the handlebars on encountering ruts, large stones or potholes, but this appears to have been an added attraction to the young men who rode ‘penny-farthings’. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s these cyclists regarded themselves as the élite of the Irish cycling world: to ride an ordinary was a test not merely of skill but also of courage. Indeed, men who rode ordinaries with brakes were deemed by their fellow enthusiasts to be unmanly. At first, not even the development in the mid-1880s of the chain-driven ‘safety bicycle’, with two wheels of equal size, enticed many Irish devotees of the ordinary away from their favourite machine. Because the first safety bicycles had solid rubber tyres, they were slower than the high-wheeled machine. While most young male cyclists rode ordinaries, older men tended to ride tricycles (which were constructed of metal from the mid-1870s onwards), as did the small numbers of Irish women who took up cycling in the 1870s and 1880s. Many of their machines were ‘Dublin’ tricycles, patented by William Bindon Blood, a native of Cranagher, in 1876.

John Boyd Dunlop on a chain-driven safety bicycle, which did not replace the ordinary or the tricycle on Ireland’s roads until Dunlop, a Scottish veterinarian practising in Belfast, demonstrated its superior capabilities when it was fitted with pneumatic tyres.

Pneumatic-tyred safety bicycles

The chain-driven safety bicycle did not replace the ordinary or the tricycle on Ireland’s roads until John Boyd Dunlop, a Scottish veterinarian practising in Belfast, demonstrated its superior capabilities when it was fitted with pneumatic tyres. At first Dunlop was motivated by the challenge of providing a more comfortable ride for his nine-year-old son, Johnnie, whose solid-tyred tricycle vibrated uncomfortably when he cycled over Belfast’s poorly surfaced roads; Dunlop then proceeded to develop a pneumatic tyre that would fit a safety bicycle. William Hume of the Cruisers’ Cycle Club, riding one of Dunlop’s pneumatic-tyred bicycles, caused a sensation when he won all of his races against solid-tyred opposition at Belfast’s Queen’s College races in May 1889, and the virtues of the new tyre were further demonstrated when a six-man ‘Irish Brigade’ of racers swept all before them on English racing tracks in 1890. Although it soon transpired that Dunlop’s patent for his pneumatic tyre was invalid, as (unknown to Dunlop) another Scot, William Thompson, had taken out a patent for a similar invention in 1845, nevertheless, in the public eye at least, Dunlop was credited as the pneumatic tyre’s inventor.

The remarkable racing successes of Hume and the ‘Irish Brigade’ helped to spark off a popular clamour for pneumatic-tyred safety bicycles in both Ireland and Britain, and the company formed by Dunlop and a number of associates in November 1889 was well placed to meet it. After a brief period of production in Dublin, the company relocated to Coventry in 1892, following a court case taken against the company by Dublin Corporation, which claimed that it represented a health hazard owing to the noxious smells arising from the rubber and naphtha used to manufacture Dunlop’s tyres and tubes. The move to Coventry probably also made sound business sense, however, as the British Midlands was then the centre of the United Kingdom’s bicycle-manufacturing industry.

Middle-class activity

A young female ‘scorcher’ at the seaside. (NLI)

Dunlop’s invention (or, more accurately, his rediscovery) of the pneumatic tyre revolutionised cycling at home and abroad. The pneumatic tyre not only rendered ordinaries and tricycles obsolete but also made cycling a much more accessible activity for a much wider range of people. While Irish cycling still remained a largely middle-class and upper-class activity in the 1890s, just as it had been in the 1870s and 1880s (while safety bicycles were certainly cheaper than ordinaries and tricycles they were still far beyond the purchasing power of most lower-class consumers), a much broader spectrum of middle-class riders took to wheels in the final decade of the nineteenth century. As its name suggests, the safety bicycle could be ridden without the hair-raising risks that riding an ordinary often entailed, and the addition of the pneumatic tyre meant that the safety bicycle offered both a relatively smoother and faster ride than any of its predecessors. Middle-class and, eventually, upper-class Irish customers of all ages and of both sexes sparked off a remarkable cycling craze in the 1890s, such was their eagerness to ride pneumatic-tyred safeties.

Members of a cycling club with their ordinaries and tricycles outside Waterford courthouse. (NLI)

Women’s liberation

The pneumatic-tyred safety bicycle was particularly welcomed by middle-class girls and women, as it freed them, at least temporarily, from the stuffy confines of their homes and provided opportunities for exercise and enjoyment that appeared revolutionary and even emancipatory to them and their contemporaries. Writing in the 1970s of her childhood years in Rathmines in the 1890s, Sidney Gifford Czira recalled that ‘Two girls from our neighbourhood, who cycled a distance of about eighteen miles, with a long rest in the middle, gained a reputation comparable to any astronaut today’. One aspect of the bicycle’s revolutionary impact is that it enabled Irish women to challenge prevailing notions about women’s physical frailty. The most spectacular instance of this occurred in 1893 when Beatrice Grimshaw, the Irish Cyclist’s female correspondent, set a world record for a 24-hour cycle by a woman by riding some 212 miles on a ‘Rover’ bicycle, beating the previous record by some five miles. Most Irish women who cycled did not go to the extremes of Grimshaw but were content to go on bicycle ‘spins’ that did not involve excessive speed or exertion; accounts of women comfortably cycling from 30 to 50 miles in a day were commonplace in the 1890s. It was considered scandalous for women to ‘scorch’ on their bicycles, and those few Irish women who wore ‘bloomers’ or ‘rational clothes’ when cycling were subjected to ridicule—or even, on occasion, physical assault. Even in the relatively liberated Irish cycling world of the 1890s, then, there were still social constraints on women’s cycling.

A female cyclist at Salthill, Co. Galway. The pneumatic-tyred safety bicycle was particularly welcomed by middle-class girls and women, as it freed them, at least temporarily, from the stuffy confines of their homes and provided opportunities for exercise and enjoyment that appeared revolutionary and even emancipatory to them and their contemporaries. (NLI)

Nevertheless, the safety bicycle enriched Irish women’s lives, as outlined by Elizabeth A.M. Priestley of Saintfield in June 1895: ‘To glide along at one’s sweet will; to feel the delight in rapid motion that is the result of our consciously exerted strength; to skim like a low-flying bird through the panorama of an ever-varying landscape; to know a new-born spirit of independence . . . to return from a country spin with a healthy appetite, a clearer brain, and an altogether happier sense of life—an altogether unaccountable freshness of spirit; this is to experience something of the joys of cycling, and in so doing to rejoice that such a good gift has fallen to modern woman as the safety bicycle’. HI

Brian Griffin lectures in history at Bath Spa University.

Read More: Early Machines

Further reading

J. Cooke, John Boyd Dunlop (Garristown, 2000).

B. Griffin, Cycling in Victorian Ireland (Dublin, 2006).

B. Griffin, All colours of the rainbow, including black and gold: making and selling bicycles in Ireland in the 1880s and 1890s. Irish Historical Studies 39 (152) (Nov. 2013).