‘More European than the rest of the Ten’? Ireland and Poland, 1980–1

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2013), Volume 21

Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa during the strike at the Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard, August 1980. (Marek Zarzecki/Reuters/Forum)

Between December 1980 and April 1981, western powers had good reason to fear that the Soviet Union was about to intervene in Poland, either in the form of a unilateral invasion or in conjunction with the Polish army, in order to suppress the social unrest that had been occasioned by the rise of the trade union Solidarność (see sidebar). On the basis of high-grade human intelligence that had been gathered by the first week of December 1980 (see page 41), NATO member states sincerely believed that such an invasion—which called forth all sorts of uncomfortable historical memories—seemed not only likely but also, quite possibly, imminent. The question of an appropriate response to such an action was discussed at great length in Washington, London, Bonn and elsewhere. Memories of western failings in response to similar developments in Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Afghanistan as recently as 1979 were fresh in the minds of western policy-makers, and there was a determination to present a united, coordinated front in the face of any such Soviet aggression.

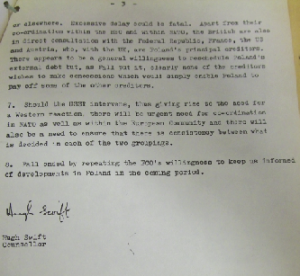

British willingness to keep Ireland ‘informed of developments’

It was in this context, on 5 December 1980, that Hugh Swift, a counsellor in the Irish embassy in London, called by appointment (and at the suggestion of the British) on Brian Fall, head of the Eastern Europe and Soviet Department of Britain’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), to ‘discuss with him the most recent developments in Poland’. Fall confirmed press reports of troop build-ups on Poland’s borders and stated that, were the requisite decision to be taken, the Soviets were militarily ready to intervene in Poland at short notice—though at that stage the British (not being privy to Kukliński’s message or the outcome of the Warsaw Pact summit) had no knowledge as to whether such a decision had been taken. Fall said that the USSR knew that the cost of such an intervention, in terms of the consequent damage to the process of détente, would be very high, but he did not venture an opinion as to whether this cost would rule out an intervention were the Soviets to consider their vital interests to be threatened. He also stated that, while NATO forces had moved to a higher state of readiness as a precautionary measure, the main focus of western response to a Soviet intervention would not be in the military field but rather in political and economic action—which action was, of course, outside NATO’s defined sphere of activity. The crucial passage ran:

It was in this context, on 5 December 1980, that Hugh Swift, a counsellor in the Irish embassy in London, called by appointment (and at the suggestion of the British) on Brian Fall, head of the Eastern Europe and Soviet Department of Britain’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), to ‘discuss with him the most recent developments in Poland’. Fall confirmed press reports of troop build-ups on Poland’s borders and stated that, were the requisite decision to be taken, the Soviets were militarily ready to intervene in Poland at short notice—though at that stage the British (not being privy to Kukliński’s message or the outcome of the Warsaw Pact summit) had no knowledge as to whether such a decision had been taken. Fall said that the USSR knew that the cost of such an intervention, in terms of the consequent damage to the process of détente, would be very high, but he did not venture an opinion as to whether this cost would rule out an intervention were the Soviets to consider their vital interests to be threatened. He also stated that, while NATO forces had moved to a higher state of readiness as a precautionary measure, the main focus of western response to a Soviet intervention would not be in the military field but rather in political and economic action—which action was, of course, outside NATO’s defined sphere of activity. The crucial passage ran:

‘Should the USSR intervene, thus giving rise to the need for a Western reaction, there will be urgent need for co-ordination within NATO as well as within the European Community and there will also be a need to ensure that there is consistency between what is decided in each of the two groupings.’

Ireland’s position as the only member of the EEC that was not also a member of NATO was thus dramatically brought to the fore. The meeting concluded with Fall stating the FCO’s willingness to keep Ireland ‘informed of developments’ in Poland.

A protest at the height of the crisis outside the Soviet Embassy, Orwell Road, Rathgar. (Irish Polish Society)

Swift received a second briefing from the FCO on the subject of NATO planning towards Poland on 17 December, this time from D.H. Gillmore, head of the FCO’s defence department. Gillmore provided Swift with details of the content and decisions of a ministerial session of the NATO council that had been held a few days previously. This had decided to draw up a list of economic and political measures that could be applied against the Soviet Union in the event of a military intervention by the latter in Poland. Gillmore stated that such an intervention would lead to a meeting of the full North Atlantic Council ‘with a view to agreeing on precise reactions’. As these reactions would include economic measures, ‘falling for the Community member states within the area of Community competence, there would be a need for co-ordination with the Community institutions’—and, of course, Ireland would be part of that Community response. Gillmore then upped the diplomatic ante by suggesting that the EEC should draw up its list of measures first, in order that the NATO council would know what type of support it could, and could not, expect from the Community. The significance of this sequencing will be discussed below.

The last page of Hugh Swift’s letter (9 December 1980) from the Irish embassy in London reporting to Dublin on his meeting with Brian Fall, head of the Eastern Europe and Soviet Department of Britain’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO). (NAI)

Swift’s third briefing from the FCO took place on the last day of the month (this time being provided by David Johnson, assistant head of the Eastern European Department), although no minute of this meeting appears on file. We can hazard an informed guess as to its substance, however, from a report submitted by Swift to Dublin on 3 February 1981, wherein he recounted a telephone conversation he had had that day with Brian Fall. Swift reported that Fall informed him that the FCO had not yet finalised its detailed work on the implementation of the NATO council decision but that it would be happy to give the Irish an update at any time if they so wished, and would certainly wish to talk once substantial progress had been made on those preparations (which he expected would take another week), ‘on much the same basis as on 31 December’. This suggests that the discussion on this date had addressed British thinking on the political and economic options open to NATO in the event of a Soviet intervention. Fall ‘again emphasised that they [whether he meant NATO or the UK is unclear, probably the former] had no ambition to cut across Community competence’—a sure signal that the British were aware that this is precisely how the matter would appear should the plans become public knowledge—but felt that contingency planning was useful.

NATO finalised its list of possible responses at a meeting on 18 February 1981, and gave detailed consideration to these during a meeting on 16 March. This concluded that, ‘in order to be most effective, economic measures should be applied simultaneously and unanimously’. It also sought ‘to ensure that certain non-NATO countries also apply these measures’. While Ireland was not mentioned specifically as one of these, the minutes of the meeting later went on to note that, ‘As far as European Community members of the Alliance are concerned, the measures falling within its competence will have to be considered by the Community’—thus ensuring that Ireland would be the focus of renewed attention.

The stage was set for Swift’s fourth FCO briefing (again with Fall), on 24 March, at precisely the time when fears of a Soviet intervention were running at their highest since the previous December. It is worth noting that Swift’s report back to Dublin expressly stated that the purpose of the meeting ‘was to discuss . . . recent developments in the state of preparedness within NATO to react to possible Soviet intervention in Poland’. During this briefing Fall gave Swift full details of NATO’s plans, and of the thinking that underpinned their preparation. A key feature of these plans was ‘explicit recognition of the particular role of the European Economic Community’.

New departure

The Department of Foreign Affairs at this point reviewed developments and concluded that a radical new departure was in order. In an internal memorandum dated 2 April 1981, it noted that Irish diplomats had up to that point refrained from commenting on the information regarding NATO planning that had been provided to them by the British ‘because we were hesitant about a procedure that might appear to amount to proxy representation in NATO’. In the words of the memo, ‘The problem for Ireland is to avoid being confronted with our partners with what amounts to a fait accompli’—i.e. that the EEC should not appear to be simply doing NATO’s bidding. The question of the sequencing of action was vital in this regard. As all contingency planning had theretofore taken place within NATO, it seemed logical that, in the event of a Soviet intervention (then feared at any moment), it would make its decisions before the EEC. If the Community then differed from NATO in its response it would produce ‘charges of being soft on the Soviets’, but if it concurred then this ‘would raise questions about our relationship to NATO’. In either case, the Community would find itself under pressure to reach a swift decision without adequate prior discussion. The memo concluded that the best way to resolve the dilemma was for Ireland to cease its bilateral contacts with Britain and to suggest directly to its Community partners that collectively they needed to prepare their own contingency plans to deal with a Soviet intervention.

A suitable occasion arose on 7 April, during the course of a dinner involving political directors of the Departments of Foreign Affairs of the various EEC member states. During the course of the discussion Ireland suggested that the Community undertake its own contingency planning to deal with a Soviet intervention in Poland. It put forward this proposal both because it ‘found it difficult to participate either indirectly or vicariously in what was a NATO process’ and because it believed that the Community should in any event prepare itself for a development that went to the heart of the ‘European ideal’. In the words of the minute of the meeting:

‘At the outset the general reaction of our partners was defensive or negative but gradually a feeling grew that firstly, Ireland had raised a legitimate problem and secondly, that a Community institutional problem also existed’.

In a memorable phrase, the Italian delegate remarked that precisely because Ireland was neutral and not a member of NATO, on the issue of a Soviet threat to Poland she ‘was in the position of being more European than the rest of the Ten’. As things turned out, the proposal did not command universal support, with the Dutch and Belgians in particular opposed to the idea, and it was dropped.

Conclusion

Of course, the Soviet Union did not invade Poland—it is, in fact, unlikely that it ever seriously contemplated doing so—and in December 1981 the Polish military, on its own behalf (albeit with Soviet backing), imposed martial law in their efforts to suppress the challenge of Solidarność. The question of what would have happened had a Soviet invasion taken place may therefore appear moot—but surveying the foregoing one may legitimately ask just how close Ireland came to de facto membership of NATO during the Soviet ‘invasion scares’ of Poland in 1980–1.

The answer must be close, but not so close as to endanger Irish neutrality. On the one hand, it is clear that Ireland was constantly updated on NATO preparations for a Soviet intervention during the months in question. During April 1981, furthermore, Ireland conducted its own analysis of the costs and benefits of each of the measures on the NATO contingency ‘menu’—in effect, ‘shadowing’ NATO’s preparations. On the other hand, at all times the Irish side was clear in its own mind that it had been invited to listen in to NATO thinking over an issue that affected all of Europe, and, quite sensibly, was doing so, but it was not contributing to its formulation and scrupulously avoided any gesture that could reasonably be construed as complicity in such planning.

Irish neutrality had, of course, been first pursued during the Nazi–Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939, and it clearly survived the Soviet threat of a repeat performance from December 1980 to April 1981. One can go further, however, and suggest a much more significant interpretation of the events covered in this article. What Ireland suggested to its European partners in April 1981 was nothing less than that, as regards Poland, the Community develop its own, distinct, common foreign and security policy—arguably for the first time in the Community’s history. Paradoxically, Ireland was ideally placed to propose such an initiative because rather than in spite of its neutrality. HI

Gabriel Doherty is a college lecturer in the School of History, University College Cork.

Read More: Soviet invasion?

Solidarnośćść

Further reading

Department of Foreign Affairs files in the National Archives, Dublin: DFA 2011-39-1739 Martial law in Poland; DFA 2011-39-1741 Trade unions in Poland; DFA 2011-39-1744 Domestic situation in Poland.

D.J. MacEachin, US intelligence and the Polish crisis 1980–1981 (Washington, 2000).

NATO documents: http://www.nato.int/ cps/en/natolive/81233.htm.