Viking Cork

Published in

Features,

Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2010),

Vikings,

Volume 18

Elizabeth Fort (left) and St Fin Barre’s Cathedral (centre) in 1796. This picture of the south bank of the River Lee shows how close the monastery of Cork (where the cathedral was later built) was to the Viking settlement at the site of the late South Gate Bridge. (Crawford Art Gallery)

Cork experienced its first recorded encounter with the Vikings in 820, when its great monastery was attacked. Yet the annals record only three further raids on Cork by Vikings from overseas in the following three and a half centuries. The first record we have of a Viking settlement at Cork dates from 846, when Irish annals report that Ólchobhar mac Cináeda, king of Munster, attacked a Viking stronghold at Cork (dún Corcaighe). There is no report of the outcome of the attack. Vikings based at Cork were active in 865, when their leader, Gnimbeolu, was killed in an encounter with the men of Decies (Waterford). The Three fragments state that the Irish then destroyed the Vikings’ castle (caisteol). The annals make no further reference to the Vikings at Cork until the twelfth century. It is important to note that those early Viking fortifications were simply raiding bases. Had they not been destroyed they might have evolved into towns, but the very limited evidence suggests that urban development in Cork cannot be traced back to the ninth century.

In 914 a great fleet from overseas devastated Munster. According to Cogadh Gaedhel re Gaillaibh, some of the Scandinavians from the great fleet settled at Cork. Those Vikings arrived at some kind of understanding with the leading men of the neighbouring monastic community. Their relationship was characterised by peaceful coexistence. The churchmen availed of the Viking merchants’ services to purchase English salt, French wine and other imported goods. Gerald of Wales, after visiting Ireland in 1185–6, reported that:

‘Imported wines . . . are so abundant [in Ireland] that you would scarcely notice that the vine was neither cultivated nor gave its fruit there. Poitou, out of its own superabundance, sends plenty of wine and Ireland is pleased to send in return the hides of animals and the skins of flocks and wild beasts.’

Only the leading clergy and local aristocracy could afford to purchase imported goods in any quantity. Without their custom Viking Cork could never have existed as a commercial entity.

In 1118 Cormac MacCarthy led a rebellion against the king of Munster and made himself king of Desmond (‘South Munster’), establishing his capital at Cork. His royal residence was the ‘old castle’ (vetus castellarium) found by the English on a rocky outcrop at Shandon (from the Irish sean dún). The fact that the English referred to it as a ‘castle’ suggests that it was a substantial structure. Nearby was a gallows, clearly implying a judicial function at Cork. It serves to highlight the significance of Cork under MacCarthy government. The MacCarthys favoured the development of the port of Cork in the twelfth century, and the town certainly grew under their auspices.

Where was Viking Cork?

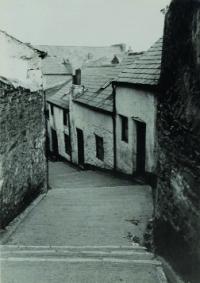

Keyser’s Hill, leading to the south bank of the Lee, close to the South Gate Bridge—the only place in Cork that still has a Viking name. (Cork City Libraries)

Between 1974 and 1977 Dermot Twohig of UCC supervised major archaeological excavations at Skiddy’s Castle, off North Main Street, and at the medieval college by Christ Church off South Main Street. Twohig concluded from his four years of excavations that ‘there was little settlement on the south island before around 1200. The north island does not appear to have been settled until about 50 years later.’ English records show that in the late twelfth century there were certainly Hiberno-Viking houses in the area around Barrack Street and Sullivan’s Quay. Of tremendous interest in this area was ‘the little harbour . . . where small ships and boats put in’ in Viking times. Its location is indicated by a tidal millpond shown on Story’s map of Cork in 1690, which reveals it as extending over the area now bounded by Meade’s Street, Cove Street, Mary’s Street and Sullivan’s Quay. An archaeological excavation in this area uncovered a stone wall that turned it into a tidal millpond in the later Middle Ages.

The significance of the ‘little harbour’ was reflected by a striking landmark—the ‘Cross of Cameleire’. It is possible that this was the earliest harbour in use in Cork. Large ships were probably anchored in the south channel of the Lee. Timber beams, believed to have been part of a jetty, were excavated on the south bank of the Lee at French’s Quay. Nearby Keyser’s Hill boasts a name of Scandinavian origin, signifying ‘a passage leading to the waterfront’, and provides further evidence of a Viking presence in the area. English charters record that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (named after Jesus’s tomb in Jerusalem) was attended by ‘the burgesses (of Cork) and others’. It occupied the site of today’s St Nicholas’s Church, off Cove Street.

In 1081 Cork’s houses and churches were burnt down in a savage attack. It may not be a coincidence that archaeologists uncovered a wooden walkway, dated by dendrochronology to 1085, extending from the south bank of the Lee towards the south island, very close to today’s South Gate Bridge. I would suggest that settlement on the south island of the Lee was given an impetus by the attack on Cork in 1081. The earliest reference to a bridge in the area comes from the mid-twelfth century: the Annals of Tigernach for 1163 report the drowning of a man who, ‘being intoxicated, fell from the bridge of Cork’.

The oldest Viking houses found in Cork to date, during archaeological excavations directed by Deborah Sutton and Máire Ní Loingsigh off South Main Street, date from c. 1100 onwards. The remains of ten houses were uncovered, built on a series of clay platforms held in place by strong wooden revetments that were designed to keep the houses above the flood levels of the Lee. Traces were found of walls of mud and wattle, door posts, sections of the bow of a small Viking boat, fragments of decorated hair-combs, shoe leather, sherds of pottery and metal artefacts, including weighing-scale measures and metal clothing pins. Many fish bones and scales were found, as well as cat skulls. Deborah Sutton stated that ‘We think the people here ate hake and pike, and they raised cats until they were a year old, and then killed them for their fur’. She cited other evidence of cruelty to pets—the snouts of dogs had been broken by severe blows, and healed imperfectly.

Gilbert mac Turgar, the last known leader of the Hiberno-Viking community in Cork, who was killed by English freebooters in 1173, had a residence on the south island, with a chapel in its courtyard. His residence may have been located close to the South Gate Bridge, on the site of the Beamish and Crawford brewery, where there was a medieval chapel dedicated to St Lawrence. The archaeological evidence points to settlement in that area dating from 1100, and to some other buildings further along today’s South Main Street dating from the first half of the twelfth century.

How big was Viking Cork?

Cork’s absence from the historical record before the twelfth century, and the archaeological evidence so far available, suggests that Viking Cork was a very small settlement prior to 1100. One important reflection of its small size is the absence of town walls made of stone. Dermot Twohig, on the basis of the archaeological evidence, and I, on the basis of historical evidence, concluded that Viking Cork had no town walls of stone. The latest archaeological excavations by the South Gate Bridge have proven the case beyond all doubt. There were no stone walls on the islands of the Lee before the English walls of the thirteenth century. The first of the English to come to Cork had to construct a fortified base in the town in 1177. Prince John, in Cork’s first royal charter (1185), directed the English community in Cork ‘to enclose my city of Cork’ (with walls), and to reserve a place for him to ‘make a fortification’. The implications of the charter are obvious enough.

Hiberno-Viking Corkonians

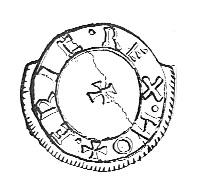

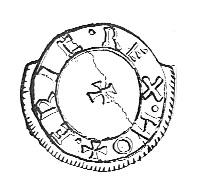

A coin ascribed to Eric ‘Bloodaxe’, king of Northumbria (947–9, 952–9)—the only Viking artefact found in Cork before the end of the twentieth century.

When, in the late twelfth century, we catch a shadowy glimpse of Cork we see that its population may best be characterised as Hiberno-Viking. It seems safe to assume that intermarriage and acculturation had done much to give Cork’s Vikings an ‘Irish’ character. They were ‘Gaelicised’ to some degree, as reflected by the name of one of their number, Malmaras Macalf (‘son of Olaf’). A man named Ua Dubgaill (‘descendant of a dark foreigner’) who held a fishery among the islands of Cork in 1199 may have been another ‘Gaelicised’ Scandinavian. There were Irish people, like Gilla Pátric mac Sinan, living on the south island of Cork. The intoxicated Muirchartach Ua Mael Sechlainn who fell from the bridge of Cork and drowned in 1163 had clearly enjoyed too much alcohol, an unfortunate indicator of the genial relations that existed between the residents of Cork and the wider Irish society of which they were an integral part. Cork’s Hiberno-Viking community were certainly Christian in the twelfth century. Their leader had a chapel dedicated to St Nicholas in the courtyard attached to his residence. Mass in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was attended by Hiberno-Vikings from Cork.

Under the jurisdiction of Diarmaid MacCarthy, king of Desmond, the citizens of Cork clearly enjoyed some degree of autonomy under their last recorded leader (duce), Gilbert mac Turgar. His property, with its court and chapel, was clearly more substantial than those of the lesser citizens of Cork. MacCarthy employed him as the commander of Desmond’s fleet, an exalted position. Cork’s trading network on the eve of the English invasion reached across the sea to England and Wales, and to France. There are written references to imports into Cork of English salt and Welsh horses. France supplied the wine that was so much in demand by the clergy and the aristocratic élites who dominated Ireland in the twelfth century. The twelfth-century carved heads from Poitou preserved in St Fin Barre’s Cathedral confirm that district as a probable source of much of the wine brought to Cork. Cork’s traders appear to have made little use of coin in south Munster and that is unfortunate, for it denies us an important means of assessing their economic impact on the region.

Archaeologists have recovered large quantities of fish bones and oyster shells in Cork. There were a number of fisheries about the islands of the Lee, which appear to have been owned by Irishmen. There were also several tidal flour mills around Cork, including one that became the ‘King’s mill’ following the English invasion and may have belonged to Diarmaid MacCarthy, king of Desmond, before 1177. These fisheries and mills hint at a significant population around Cork and its environs on the eve of the invasion.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly small by European standards, the settlement at Cork was of great importance for the kings of Desmond in the twelfth century. They resided in a castle overlooking Cork to the north of the Lee. That sean dún had important administrative and judicial functions, and may itself have been the focus for an Irish settlement. In 1177 English knights went to Cork, captured and plundered the town and established a fortification there. Many, if not all, of the surviving citizens were expelled from their property in Cork and they vanish from history thereafter. The immigrants from south-western Britain who succeeded them were to build upon the Viking foundations of the city of Cork. HI

Henry A. Jefferies is the Head of History at Thornhill College, Derry.

Further reading:

H.A. Jefferies, A new history of Cork (Dublin, 2010).