Ulster Unionist Propaganda against Home Rule 1912-14

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Home Rule, Issue 1 (Spring 1996), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 4

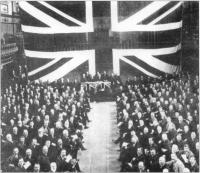

Ulster Covenant Day, 28 September 1912

We live in an age of media gurus, spin doctors and soundbites, when advertising agencies have been invested with almost divine powers to sell policies, transform images and win elections. The now familiar relationship between the mass media and politics first made an impact in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. These years witnessed the emergence of a mass society: mass production, distribution, consumption, education and literacy and also mass politics based on an extended franchise, a swollen electorate and large political parties and party machines. This transformation resulted in mass participation in the political process and marked a decisive break with an era in which only the opinions and decisions of a small elite mattered. Henceforth, just as in business the working class consumer had to he persuaded to buy the product, so in politics party policies had to be sold to the hundreds of thousands of new voters.

Carson:’Take it away, it smells;been buried twice already;bury it again,this time for good.’

The power of the press

Sophisticated techniques of persuasion existed in a newly-created advertising industry which by 1900 involved dozens of agencies based in London with tens of thousands of employees. Its most important instrument was a national press serving a relatively small state through an efficient railway system and whose newspapers delivered to British businessmen a national market which could he exploited through newspaper sales campaigns. And newspapers became ever more important as new production techniques such as photographs and the use of headlines boosted sales to previously unimaginable levels. This media revolution was replicated in miniature in Ulster, where the unionist Belfast News Letter, Northern Whig and Belfast Evening Telegraph and the nationalist Irish News serviced the province and were supplemented by a host of local publications such as the Derry People and the Tyrone Courier.

The pre-eminent position of the newspapers was symbolised by the emergence of press lords, immensely wealthy and politically influential newspaper proprietors such as Lords Beaverbrook, Northcliffe and Rothermere in Britain, Sir John Arnott in Ireland where his Irish Times was the most prosperous publication and, on a smaller scale, the Baird brothers, the owners of the Belfast Evening Telegraph. The Bairds grew rich because of the seemingly insatiable appetite in Ulster for newspapers, demonstrated in 1893 when their paper achieved a record circulation of 70,000 copies on the day the second Home Rule bill was introduced by Gladstone—and that was before a ‘Home Rule special’ at one o’clock the following morning, carrying the result of the vote in the House of Commons, was bought by 5,000 people.

James Craig: publicity director

The unionist political and business elite of Ulster had adapted well to the new era by the time of the introduction of the third Home Rule bill in 1912 and become adept at mobilising public opinion and advertising campaigns. James Craig MP, the future prime minister of Northern Ireland, for instance, with his knowledge of the techniques of marketing and mass persuasion gained from his family’s connection with Dunville’s whiskey, became effectively the publicity director of the Ulster unionist movement in its campaign against Home Rule. Craig had at his disposal virtually unlimited financial resources to fund the propaganda campaign against the bill since he was a leader of a movement which had easily raised an indemnity fund of one million pounds.

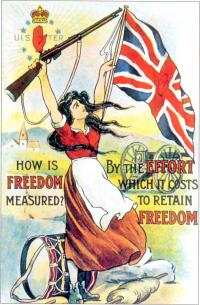

The propaganda blitz against Home Rule between 1912 and 1914 was conducted on the lines of a two-year advertising campaign utilising every available media resource including newspapers, cartoons, books, postcards, placards, posters, pamphlets, leaflets, songs, banners, photographs, film, badges, brooches and even towels. There were also lectures, parades, demonstrations, guided tours and sermons in church. The professionalism of the unionist campaign was augmented by the assistance of local journalists such as Thomas Moles, the leader writer of the Belfast Evening Telegraph, and R.M. Sibbett of the Belfast News Letter, who gave sympathetic and wall-to-wall coverage of events such as the Ulster Covenant in 1912 and the Larne gunrunning of 1914. Moles, a future editor of his paper, was an intimate of Carson and Craig and actually wrote many of the anti-Home Rule pamphlets published by the Ulster Unionist Council as well as ghosting pro-unionist articles for the British press.

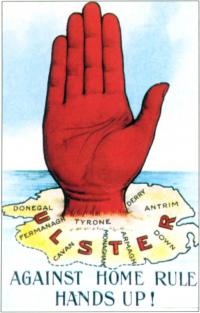

Effective propaganda techniques used by the Ulster Unionists included: the continual repetition of a simple message about loyalty to the Crown and Empire; the use of catchy slogans such as ‘Home Rule means Rome Rule’, ‘Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right’ and ‘No surrender’; the visual appeal of exciting drama, spectacle and colour involving demonstrations, banners, regalia, sashes and flags, including the largest Union Jack ever made which was displayed at a monster Unionist rally in the Balmoral showgrounds in 1912. There were representations of emotive episodes from Ulster’s past such as the breaking of the seige of Londonderry by Mountjoy in 1689, great figures past and present such as William of Orange and Carson, symbols such as the Red Hand of Ulster and biblical episodes considered to have immense contemporary relevence to Ulster Protestants such as Moses leading the exodus of his people out of slavery in Egypt. There were also the cinematic-like entrances of heroic figures such as Carson and the military bearing of members of the Ulster Volunteer Force who struck an emotional chord with a public long familiar with advertising heavily based on heroic soldiers and sailors and celebrated incidents from the history of the British Empire.

Four different audiences: unionists themselves

Unionist propaganda was directed at four different audiences and had correspondingly different purposes. The first target was Ulster unionists themselves. The propaganda was designed to inspire them, achieve the maximum mobilisation of the rank-and-file and integrate them into a united popular resistance movement. It also sought to reinforce their belief in the righteousness of the cause, to re-assure them that their leaders were fully committed to the cause and would not betray them, to re-affirm that they were all part of one unionist family and to inspire them with the belief in ultimate and certain victory. Propaganda also acted as a recruiting agent for the Ulster Volunteer Force and publicity coups such as the Larne gunrunning of April 1914 were crucial (See HI spring 1993). Until then there were still many waverers such as the ‘border’ Protestants of Fermanagh, Tyrone and Donegal, whose minority position had encouraged them to keep a low profile in 1912 and 1913. Now many of those doubters were persuaded that resistance to Home Rule could succeed and enlistment in the UVF soared in those areas.

Unionist morale was sustained by staged demonstrations of daring and skill. The Signalling and Dispatch Rider Corps, for instance, caught the imagination as early as July 1913 during a UVF camp of instruction at Tynan Abbey in County Armagh when a flying column of motor cyclists was mobilised for an exercise involving a reported enemy advance across the Boyne at Drogheda. Travelling with orders to ‘destroy’ the bridges, mine the fords, destroy the railways at Drogheda and seize rolling stock, they made a sixty-mile journey under dark through Crossmaglen, Dundalk and Dunleer before placing a Union Jack on the obelisk of William of Orange and posters on bridges announcing that they had been ‘captured by the Ulster Volunteer Force’.

Belfast under Home Rule- making a site for a statue of ‘King John I of Ireland’. The ‘Protestant emigration office’

notice reads: ‘Tickets for New York or anywhere’.

British public opinion

The second target was the British public. The Home Rule struggle in Ireland was in part an ideological battle between two irreconcilable concepts of Ireland, a British vision and an Irish one and the Ulster unionists believed that it was vital to win the hearts and minds of a British electorate which they regarded as open to persuasion. They especially sought to cultivate the British reporters and war correspondents who flooded into Ulster in 1914 and were billeted in the Grand Central Hotel in Belfast in the confident expectation that the province would soon be the natural successor to the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. Craig and his followers sought to counteract the damaging stereotype of themselves as violent anti-Catholic sectarian bigots; instead British newspapers carried accounts and photographs of sober, respectable middle class citizens marching in perfectly disciplined processions to and from churches to be greeted by clergymen. Indeed propaganda enabled unionists to claim the high moral ground by highlighting examples of alleged nationalist discrimination and intimidation. There was a particularly intensive campaign against the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Catholic equivalent of the Orange Order whose 100,000 members were depicted as the hidden but real power in the Home Rule movement, manipulating ‘puppets’ such as John Redmond. Among Protestants the AOH had acquired an unsavoury reputation for bribery, personation, intimidation and ‘jobs for the boys’ and unionist efforts to depict themselves as victims received a tremendous boost by a brutal and highly publicised attack in June 1912 by a party of Hibernians on a Protestant Sunday school outing of Belfast school children at Castledawson in County Londonderry. Coming as it did only months after the introduction of the third Home Rule bill Castledawson seemed to confirm the most apocalyptic predictions of the fate which awaited unionists in a Home Rule Ireland. The AOH then was a propaganda gift to the Ulster unionists because it enabled them to reverse the damaging image of them as the aggressors and depict themselves as the innocent victims of nationalist intolerance. Many Protestants were described as living permanently under the lethal threat of what would nowadays be termed ‘ethnic cleansing’ if the Home Rule crisis ended in civil war and considerable publicity was devoted to the arrangements being made to evacuate Protestant women and children from the outlying areas of Fermanagh, Tyrone, Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan.

The propaganda campaign against nationalists was at times based, either intentionally or otherwise, on grotesque exaggeration or absolute invention. Some of the worst examples of this ‘black propaganda’ were the allegations that Belfast Catholics were conducting raffles for Protestant homes, property, land, businesses and jobs—to he claimed by the winners on the day Home Rule became law—and that unionists had been told by nationalists to enjoy the Twelfth of July since it would he the last one ever to be celebrated. There was even the claim that the oath of the AOH pledged members to ‘aid and assist with all my might and strength to massacre Protestants, cut away heretics, burn British churches and abolish Protestant kings’. Such claims were effective in keeping the Home Rule movement on the defensive and Joseph Devlin, Home Rule MP for West Belfast and President of the AOH, was actually forced to deny the accusation in parliament.

Asquith’s government

Asquith’s government

The third target of unionist propaganda was the British Liberal government of Herbert Asquith, which was regarded as too susceptible to the assurances of its nationalist allies that unionist opposition to the Home Rule bill was largely a campaign of bluff. A military intelligence report of a Home Rule meeting in Dublin 1912 noted that ‘the prime minister’s comment “I am not satisfied that Ulster is in earnest” was regarded as a challenge and keenly resented in Ulster. It was freely said that they would soon make the government understand that they were in earnest’. The campaign to change that perception did eventually succeed as Asquith was forced, by the sheer strength of unionist opposition, to contemplate partition proposals which he had once dismissed. By June 1914 Augustine Birrell, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, after a tour of Ulster submitted an overwhelmingly gloomy assessment of the situation to the cabinet. He had found the UVF well armed and drilled and eager for some resolution of the Home Rule crisis. He ended, ‘unless some agreement…is arrived at I am certain Sir Edward Carson will he compelled to raise the flag somehow or another in Belfast whenever the unamended Home Rule bill becomes law’.

Nationalist Ireland

Nationalist Ireland

Unionist propaganda, directed at its final target, Irish nationalists, was intended to ridicule the very idea that such people could ever be entrusted with the management of a modern industrialised state. It was assumed that they lacked the skills, intelligence and organisational ability and that if the destiny of Ulster was entrusted to them the inevitable result would be economic ruin. One unionist writer satirised the first cabinet meeting of a future Home Rule Ireland as a deadly combination of incompetence, fractiousness and buffoonery:

The business commenced with one Minister—I decline to reveal his name—reflecting upon the mother of another Minister, who had already spoken for an hour and a half. Then someone called the first speaker a low blackguard, and offered to fight him in any locality he might name. In ten minutes the six old leaders of the six opposing factions had sprung to their feet, and each had called the other five liars, with a promtitude that seemed due to the baton of a musical conductor.

The meeting eventually concludes with a fracas in which ministers hurl coal scuttles, iron despatch boxes and fenders at each other.

Unionist propaganda also amounted often to psychological warfare designed to impress, overawe and intimidate them into a realisation that in Ulster the political and military initiative lay firmly in the hands of their opponents. As late as February 1914 their leader Joseph Devlin, the most important Home Ruler in the province, was stating that ‘Home Rulers regard the whole thing with absolute contempt and are astonished that anybody outside Belfast  should take it seriously’. Thereafter, however, came a mounting sense of alarm culminating in the shock of the Larne gunrunning, with the concern increased by ominous statements from some unionist leaders such as Lord Clanwilliam who boasted in July 1914 that

should take it seriously’. Thereafter, however, came a mounting sense of alarm culminating in the shock of the Larne gunrunning, with the concern increased by ominous statements from some unionist leaders such as Lord Clanwilliam who boasted in July 1914 that

if war did break out it would probably be a war of extermination. We have the nationalists sandwiched between our forces and they have only a few old guns to rely on. They could not possibly have a chance. Our men are well armed and guns and ammunition are constantly being run into Ulster. We have the province in the hollow of our hands.

The considerable superiority in weaponry, leadership, expertise and organisation of the UVF kept the Irish Volunteers on the defensive and in a calculated and chilling reminder to nationalists, as well as to the British government, Carson, in July 1914, sanctioned large parades of armed members of the UVF in Belfast. The largest one consisted of 4,000 members of the East Belfast regiment parading through the city centre, carrying Mauser rifles and accompanied by two Maxim machine-guns and four Colt quick-firing guns mounted on platforms and pulled by ropes. Police and army made no effort to interfere in any way.

These parades were a stunning propaganda success for Ulster Unionists . All eyes that day were on Belfast as they demonstrated in the most devastating manner that they, in effect, controlled the city. Asquith’s government sank further into derision and relations between it and its Irish nationalist allies were severely damaged at this very public display of the absolute helplessness of the authorities.

Conclusion

No propaganda campaign can he effective on its own, divorced from reality. Two things made that of the Ulster unionists against Home Rule a success. First, while as with all such campaigns there was a measure of exaggeration, it was founded in a passionate sincerity, a genuine belief that a culture and future was in deadly peril. It was the absolute determination to defeat that perceived threat which gave the campaign of opposition such tremendous emotive power. Second, by 1914 at the latest, it was undeniable that, whatever class, regional or doctrinal differences divided them, Ulster Protestants in the mass had concluded that what they had in common was infinitely more important. That meant that the photographs and newsreel images of vast united crowds were not simply an illusion created by Craig but reflected the reality.

Michael Foy is Head of History at Methodist College, Belfast.

Further reading:

R. Opie, Rule Britannia (Harmondsworth 1985).

A.T.Q. Stewart, The Ulster Crisis (London 1967).

B. Loftus, Mirrors: Orange and Green (Dundrum 1994).

J. Killan, John Bull’s Famous Circus, Ulster History through the Postcard 1905-1985 (Dublin 1985).