TV eye: Green is the colour

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 5 (Sept/Oct 2012), Reviews, Volume 20

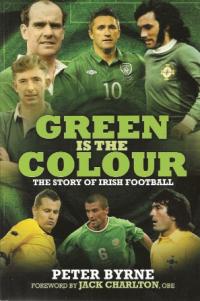

Green is the colour—presenter Darragh Maloney at the Aviva Stadium, Dublin. (RTÉ Stills Library)

Green is the colour was a four-part history of association football—‘soccer’ in Ireland—launched in conjunction with a book of the same name co-authored by veteran sports journalist Peter Byrne (Green is the colour: the story of Irish football by Peter Byrne, Carlton Books, £14.99) and presumably intended as a prelude to what turned out to be the dismal failure of the Republic of Ireland at Euro 2012. Ireland is, obviously enough, a small country, and in recent years similarly small countries such as Croatia and Uruguay have punched above their weight at major football tournaments. The Ireland–Croatia match in Poznan saw one small country humiliate another. The skills deficit was obvious, but there is a distinctively Irish factor that may account for the relative paucity of Irish soccer talent: the presence of great rivals, in the form of Gaelic games and rugby union. Both the GAA and the IRFU are quite capable of myth-making, but both organisations received massive boosts in the new millennium with, on the one hand, the reconstruction of Croke Park and, on the other, the success of professional Irish rugby at provincial and international level. The fact is that Irish soccer has been left behind. Yet this may simply be the latest manifestation of a sporting argument that began back in the nineteenth century.

Green is the colour consisted of four episodes, all of which were presented by Darragh Maloney, lavishly illustrated with some often striking footage and adorned with a wide range of talking heads (albeit with one very obvious, if unsurprising, absentee). The first was perhaps of greatest historical interest, dealing as it did with soccer in Ireland from 1880 to 1930. The general principle of football is nothing new (the Statutes of Galway made reference to a game of this kind as early as 1527) but the Victorian era saw a variety of previously incoherent games being codified and formalised—rugby, soccer and, in Ireland, Gaelic football. This trend went hand in hand with the Victorian emphasis on masculinity and physical culture, not to mention the increasing commercialisation of sport as a leisure activity for the British working classes. It should come as no surprise, then, that the obvious entry point for association football into Ireland was the industrial north-east, with the founding of Cliftonville FC in 1879 by the Belfast businessman John McAlery. Belfast would remain the heartland of Irish soccer for decades. But the distinctively Protestant composition of the north-east may have hamstrung soccer’s development outside Ulster; the pejorative term ‘garrison game’ reflects one means by which soccer spread across the rest of the country.The first official Irish international match, organised in 1882 by the Irish Football Association, based in Belfast, resulted in a 13–0 defeat by England; an Irish team would compete in the ‘Home Internationals’ against England, Wales and Scotland until the 1920s. The foundation of the GAA in 1884, however, upped the stakes for domestic sport, with the declaration of what was effectively a culture war. The intensely politicised nature of the GAA, the ruthlessness of its notorious ban and, of course, its intensely localised structures made it a formidable opponent to its rivals, and it won the war decades ago. The cultural and political implications of sporting traditions are of great importance to their respective histories, although, as Mícheál Ó Muircheartaigh pointed out, there was a practical reason for the relative success of Gaelic football and hurling in rural areas: as games played in the open air and requiring large open spaces, they simply were not suited to the confines of towns and cities.

Green is the colour consisted of four episodes, all of which were presented by Darragh Maloney, lavishly illustrated with some often striking footage and adorned with a wide range of talking heads (albeit with one very obvious, if unsurprising, absentee). The first was perhaps of greatest historical interest, dealing as it did with soccer in Ireland from 1880 to 1930. The general principle of football is nothing new (the Statutes of Galway made reference to a game of this kind as early as 1527) but the Victorian era saw a variety of previously incoherent games being codified and formalised—rugby, soccer and, in Ireland, Gaelic football. This trend went hand in hand with the Victorian emphasis on masculinity and physical culture, not to mention the increasing commercialisation of sport as a leisure activity for the British working classes. It should come as no surprise, then, that the obvious entry point for association football into Ireland was the industrial north-east, with the founding of Cliftonville FC in 1879 by the Belfast businessman John McAlery. Belfast would remain the heartland of Irish soccer for decades. But the distinctively Protestant composition of the north-east may have hamstrung soccer’s development outside Ulster; the pejorative term ‘garrison game’ reflects one means by which soccer spread across the rest of the country.The first official Irish international match, organised in 1882 by the Irish Football Association, based in Belfast, resulted in a 13–0 defeat by England; an Irish team would compete in the ‘Home Internationals’ against England, Wales and Scotland until the 1920s. The foundation of the GAA in 1884, however, upped the stakes for domestic sport, with the declaration of what was effectively a culture war. The intensely politicised nature of the GAA, the ruthlessness of its notorious ban and, of course, its intensely localised structures made it a formidable opponent to its rivals, and it won the war decades ago. The cultural and political implications of sporting traditions are of great importance to their respective histories, although, as Mícheál Ó Muircheartaigh pointed out, there was a practical reason for the relative success of Gaelic football and hurling in rural areas: as games played in the open air and requiring large open spaces, they simply were not suited to the confines of towns and cities.

One of several by-now-familiar World Cup play-off heartaches for the Republic of Ireland—Noel Cantwell (second from right) can only watch in anguish as a shot from Antonio Ufarte leaves goalkeeper Pat Dunne stranded for Spain’s winner in Paris in November 1965. (Central Press/Getty Images)

The GAA did not compete in any international arena, however, and the main focus of the series was on Ireland’s role in the international game. Partition made the formation of two soccer authorities almost inevitable, and the government of the Free State favoured the idea of a sporting body that would have a distinct international identity. After the first episode, this history of Irish soccer fixed its attention south of the border. The first Irish full international was against Italy in Turin in 1926, and the exclusion of the Free State from the Home Internationals meant that the new FAI was forced to look to Europe for opponents: amongst a wide range of impressive footage in the series is the disconcerting image of the Nazi salute being given in Dalymount Park in the 1930s prior to a match against Germany.The golden age of the domestic league came in the 1960s, with massive attendances and some notable results, but the advent of BBC’s Match of the Day in the 1970s—and the prospect of watching a patently superior product in one’s living room—was a killer blow to the league. At the same time, did the emergence of Dublin GAA (as opposed to GAA in Dublin) siphon support away from soccer in its southern heartland? It would have been interesting to incorporate a more sustained comparison with Ireland’s other sporting traditions (the sight of Eamonn Dunphy crying as he recalled the euphoria surrounding the victory over Romania in Italia 1990, and the sense that Irish soccer had finally arrived, suggested that this warranted an episode in itself). The same could be said of soccer support amongst the Irish diaspora, most evidently in relation to teams such as Celtic, Everton and even Rangers, even aside from the vexing irony that so much Irish soccer support is directed at British teams.

Roy Keane—on the book’s cover but an obvious, if unsurprising, absentee amongst the wide range of talking heads in the documentary. (whoateallthepies.tv)

There were many issues that could have been touched upon in this series, and there was a touch of superficiality about the later episodes. But Green is the colour was an enjoyable whirlwind tour through Irish soccer, and ended with a striking montage of the Irish team’s high points over the last two decades. The dreadful performances of the Irish team at Euro 2012, however, brutally punctured the optimism fostered by reaching a major international tournament for only the fifth time in the team’s history: given the abject spectacle that played out in Poland, League of Ireland players could hardly have done worse. Perhaps there is a lesson to be learned from that. HI

John Gibney is History Ireland news editor.