TV Eye

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 5 (September/October 2013), Reviews, Volume 21The Big House

TV3, April/May 2013

Big Mountain Productions

by Adrian Grant

Above: On the steps of Strokestown House, Co. Roscommon—the thirteen local people, whose ancestors all worked in ‘big houses’, who spent a week living and working as servants there.

The story of the ‘big house’ and the landed estates is essentially the story of rural Ireland. Every aspect of life was affected by the fortunes of the landed class and their vast estates. Whether you were a domestic servant, a tradesman, a labourer or a tenant, a man, woman or child, your life would touch, or somehow be touched by, the ‘big house’. This fact seems to have dawned on both historians and the general public in recent years. Studies of the ‘big house’ and landed estates are becoming more plentiful and their subject-matter more wide-ranging. Public interest is also increasing, with many people reading about landed estates, attending academic conferences and digging through landed estate archives in attempts to build family trees. It is the lives of the servants and the estate employees, however, which seem to be enjoying public enthusiasm at the moment. The popularity of Downton Abbey, for instance, makes it clear that people currently have an appetite for finding out more about the ‘ordinary’ people and their role in ‘big house’ life.

Tapping into this popularity, Big Mountain Productions have adapted their well-received format for The Tenements to suit rural Ireland. The structure of the programme is fairly straightforward. Strokestown House in County Roscommon is brought back to life when thirteen local people, whose ancestors all worked in ‘big houses’, spend a week living and working as servants there. We follow these servants (aged 10–50) through their fish-out-of-water experiences in serving the lord and lady of the house. This living history/reality show format is combined with conventional historian ‘talking heads’ sections. The presenter (a fantastic Bryan Murray) then goes into the archives and picks out relevant material that illuminates the reality of what we are seeing and hearing in the other sections. The format is completed with the inclusion of some illuminating interviews with former domestic servants. The stories they have to tell are from a more modern era than that in which the reality show participants are living, but they fit in well and add an extra dimension that gives the programme more bite.

These components work very well together. It has to be remembered that this programme is aimed at a wide audience rather than the more sectional audience of, say, RTÉ’s Hidden History series. One could be forgiven for assuming that the programme-makers would sacrifice decent analysis for an extended scene where a teenager might throw a tantrum when they realise there was no Wifi in 1845. Thankfully, this does not happen and the teenagers involved in the production are quite humble in reaction to their new lives as domestic servants. The commentary by historians such as Mary E. Daly, Diarmaid Ferriter and Terence Dooley (who is credited as series consultant) is then subtly expressed to give a wider context to the situations in which the living history participants find themselves. From this we are presented with information on issues like the rise and fall of the ‘big house’, architectural designs that ensured that servants could not be seen from upper windows, female employment demographics, the stratification of the servant class, life during the Great Famine and the decimation of the cottier class.

A historical television programme such as this will never tick every box, or go into detail about every issue mentioned by the contributors. Nevertheless, some important issues are raised that bear thinking about for both historians and those with a general interest in Irish history alike. One striking example is the statistic showing that at the turn of the twentieth century 98% of upper-class households and 71% of middle-class households in Dublin employed servants. The fact that middle-class (most likely Catholic) households often employed servants speaks volumes about some of the class divisions that are often glossed over in Irish history-writing.

At one point Terence Dooley compares the ‘big house’ and landed estate to the multinational corporations of today, in that they provided large-scale employment in rural areas and could devastate an area if they were to relocate. Diarmaid Ferriter’s sobering commentary makes it clear that while those who were employed in the ‘big house’ were much better off than those outside the demesne walls, these institutions were oppressive and exploitative. The tax avoidance techniques and rules on trade union membership in some of the multinationals based in modern Ireland would suggest that Dooley’s comparison could be taken even further.

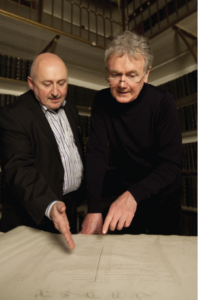

Series consultant Terence Dooley (left) and presenter Bryan Murray (right) consult estate records to pick out relevant material that illuminates the reality of what we see and hear in the other sections.

(All images: Big Mountain Productions)

The extensive archives available for the study of ‘big house’ life are put to good use. Bryan Murray is forthright in telling us that it is difficult to find information on the servants, given that the records we have were mostly left by the gentry. Nevertheless, the programme-makers have used the available sources quite well. For example, Olivia Bellew’s letter complaining that the servants at Mount Bellew should receive only one salt herring rather than two speaks volumes about the attitudes towards those ‘downstairs’. Perhaps a perusal of the house account book in a similar period would have hammered the point home. In these we usually find large quantities of lobster, veal, oysters and fine wines being consumed at times of great poverty in Ireland.

The fact that The Big House was allowed to play out over four 45-minute episodes means that we are treated to a relatively deep and wide look at ‘big house’ life, but the enormous amount of repetition between episodes and after ad breaks reaches a crescendo of annoyance that becomes almost unbearable to listen to. By episode four, it feels like we’ve been told hundreds of times that P.J. Massey (the living history butler) is the nephew of Strokestown House’s last serving butler. Is the information-retention of the Irish viewing public really that bad? In an age of on-demand, live pausing and streaming television, are these American-style recaps of things that happened five minutes ago really necessary? Despite this gripe, The Big House is an entertaining and informative programme that should be of interest to a wide variety of people. HI

Adrian Grant is a post-doctoral researcher at the Moore Institute, NUI Galway, currently researching the lives of ‘big house’ and landed estate employees in Connacht and Ulster.