TV Eye

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2007), Reviews, Volume 15

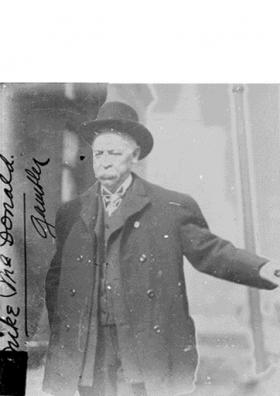

‘King’ Mike McDonald set up his criminal empire in Chicago in the aftermath of the Civil War

Gaelic gangsters

Mobs Mheiricea

TG4, October–November 2007

ABÚ Media

by John Gibney

The gangster is one of the iconic American characters of the twentieth century. In the movies that made him prominent, he usually lives in New York or Chicago, and more often than not he can speak Italian. For despite the occasional appearance in films like State of Grace or The Departed, the Irish-American gangster is vastly outnumbered in popular culture by his Italian-American counterpart. But just as millions of Italians emigrated to North America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, so too did millions of Irish. Despite what is assumed to be a classic collective rags-to-riches story, not all of them or their descendants made their living within the law.

Mobs Mheiricea tells the story of six Irish-American criminals, whose lives and careers stretched from the 1830s to the 1970s. The first was Michael ‘King Mike’ McDonald, born in Niagara Falls in 1839 to parents from Cork. After growing up in New York he began working as a vendor on the railways, identifying the lucrative potential of gambling in New Orleans before ending up in Chicago, where he set up his burgeoning criminal empire in the aftermath of the Civil War.

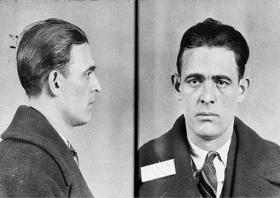

Jack ‘Legs’ Diamond

McDonald also got involved in the Democratic Party, and he and his organisation came to dominate (and exploit) the city’s politics. By the time of his death in 1907 he had added newspapers and racetracks to his gambling interests, and controlled much of the apparatus of the city. Chicago was an obvious place for such a rise to power and prominence. As the gateway to the mid-west, it had grown at a frightening rate throughout the nineteenth century to become the second city of the US, attracting emigrants in their hundreds of thousands.

Dion O’Bannion’s parents were from Kilkenny but had settled near Chicago, where he was born in 1892, and his career was perhaps more in line with the received image of the Chicago gangster. While McDonald had excelled in both gambling and the skulduggery of the city’s politics, O’Bannion began his career as a hired thug for the Chicago Tribune (and later its rival, the Herald) as the papers sought to carve out their territories, but, like many, his career was made by Prohibition. He carried out the city’s first liquor hijacking in December 1921. An immensely charming man (he was the prototype for many of James Cagney’s characters, and his official trade was as a florist), he was eventually shot dead in his shop at the behest of increasingly disgruntled Italian rivals such as Al Capone, whom he had delighted in provoking. Interestingly, despite a huge funeral, the Catholic Church refused to let O’Bannion be buried in consecrated ground.

The careers of these brutal men overlapped in more ways than one. Owney Madden was born in Liverpool but came to prominence in New York. Chicago may have been the gateway to the mid-west, but New York was the gateway to America. Like McDonald, Madden became wrapped up in the corrupt politics of his adopted city, centred on the notorious Tammany Hall, before making his fortune in the same way O’Bannion had: in the liquor trade during Prohibition, during which time he opened the legendary Cotton Club. Yet he knew that the Irish mob was in a minority: Madden was the only Irish-American mobster to attend the 1929 meeting in Atlantic City that supposedly saw the Italian and Jewish criminal organisations agree to consolidate and organise their power. One consequence of this was the killing of another Irish-American: Jack ‘Legs’ Diamond. While Hollywood has probably skewed the perception of organised crime in America, it shouldn’t be forgotten that in its heyday in the 1920s some of these

Dramatic reconstruction of the shooting dead of Dion O’Bannion in his florist shop at the behest of Italian rival Al Capone.

criminals could become celebrities in their own right. The ruthless, glamorous, seemingly bulletproof Diamond (at least until he was shot in 1931), the son of emigrants from Clare, was one of these. But this should not obscure the reality of his career: Diamond went from smuggling alcohol to smuggling cocaine and heroin. His early death can be contrasted with that of Madden, who went into more legitimate business as a gambling magnate in Arkansas, dying peacefully in 1967, though not before a young Bill Clinton had apparently been one of his customers.

It is impossible to look at this series without characters and events from innumerable gangster films coming to mind. Legs Diamond had enjoyed, however fleetingly, the celebrity of a movie star, and the activities of some of these individuals made their way into cinema. John ‘Cockeye’ Dunn was a particularly brutal figure in the New York longshoremen’s union, whose influence was exploited by the US Navy in World War II to ensure that the docks ran smoothly. The immunity from prosecution that was the other side of this arrangement did not outlive the war, and Dunn

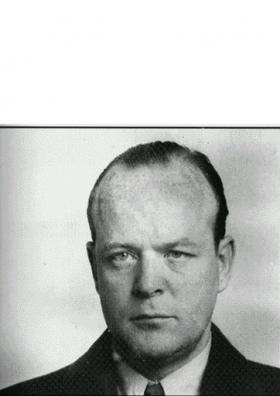

John ‘Cockeye’ Dunn

eventually ended up in the electric chair. But both he, and some of the events surrounding his career, inspired much of the classic On the Waterfront. The longshoremen’s union was also the ground upon which the equally brutal Danny Green of Cleveland made his criminal career. Whether deliberately or not, Jack Nicholson’s Irish-American mobster in The Departed resembled Green in at least one respect: he was also an informer for the FBI. Given Green’s ostentatious fascination for all things Irish, the manner of his death seems ironic. He was killed in 1977 by an Italian-American car bomb.

Many issues recur throughout this series: the Irish involvement in corrupt municipal politics, gambling, prostitution, murder, smuggling, the alcohol and drugs trades, unions, not to mention attempts to win favour from the US authorities by posing as concerned patriots. In the case of Green, it also touched on the kitsch sentimentality that is so

Owney Madden

unfairly assumed to characterise all of Irish-America, some of whose members had their own interpretation of how America could be a land of opportunity. The Irish in America were once among the lowest on the immigrant ladder. Now, many of them have become an identifiable, powerful and wealthy establishment in their own right. This series, despite its limitations, tended to make one wonder just how some of the Irish, and their descendants, might have made that transition.

John Gibney is an IRCHSS Government of Ireland fellow at the Moore Institute for Research in the Humanities and Social Studies, NUI Galway.