Truth and history

Published in Issue 6 (November/December 2020), Platform, Volume 28By Padraig Yeates

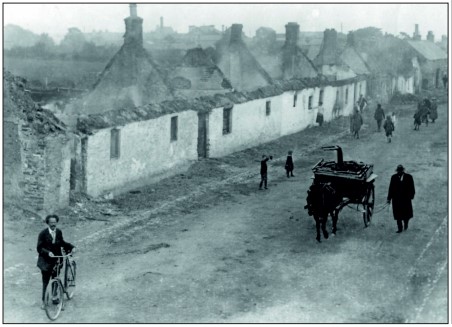

Above: The aftermath of the sacking of Balbriggan by Black and Tans on 20 September 1920. On the occasion of its centenary President Michael D. Higgins said: ‘If forgiveness and forgetting did not exist, we would be trapped in the past where every previous action would be irrevocable and where the present is dominated, burdened even, by preceding events and memories’.

In a decade overshadowed by centenaries it is perhaps inevitable that 50th anniversaries are somewhat neglected, particularly south of the border, where the more recent Troubles are often regarded as less relevant to the story of nation-building, or even as too problematic and recent to be addressed in a historical context. Yet, as President Higgins said on the recent centenary of the Sack of Balbriggan, ‘If forgiveness and forgetting did not exist, we would be trapped in the past where every previous action would be irrevocable and where the present is dominated, burdened even, by preceding events and memories’. This article argues that truth recovery is better than either oblivion or keeping score.

It is almost too late to retrieve much firsthand information from the earliest and bloodiest years of the more recent Troubles, or to capture the fear that permeated communities and drove them into conflict. Many of those directly involved have died or are approaching the end of their lives. Even materials that have been assembled, such as the Boston College Tapes and TV documentaries, are inhibited by threats of libel or criminal prosecution. They also tend, like sources for the earlier Troubles, to be one-dimensional and fail to interrogate the subjects to any great degree. No doubt many of those interviewed are as honest as memory, social pressures and the desire not to incriminate themselves, or others, allow.

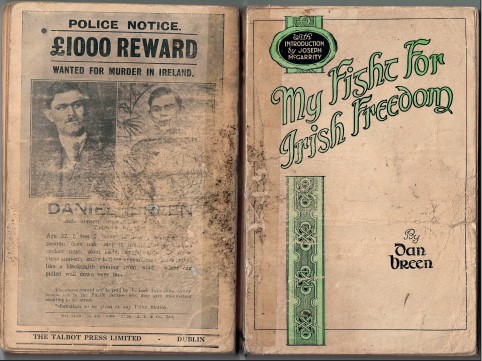

This treatment of events and people whose testimony is largely untrammelled by alternative narratives is a result of the conditions under which it is recorded. Put another way, would figures such as Tom Barry, Dan Breen or Ernie O’Malley have written the books they did if they knew that they would have to engage with those at the receiving end of their activities or with grieving kin?

About eighteen months ago, largely arising out of the Legacy Consultation presided over by Judith Thompson, the former Commissioner for Victims and Survivors of the Conflict in Northern Ireland, a number of combatants, academics, community activists and survivors, some of them wearing more than one of these hats, began a discussion that evolved into a proposal for a Truth Recovery Process (TRP). This process is not an alternative history, but the creation of a historical record of recent violent events on these islands will be deeply flawed and incomplete without it.

The TRP is intrinsically more challenging than traditional approaches to recording past conflicts. The aim is to bring together people at either end of the violence equation to make sense of what happened in their own terms. It is specifically aimed at those involved in particular incidents, be they shootings or bombings, in ways not allowed for at present by the law, or by the politicians who frame those laws on our behalf.

It is not a form of reconciliation as the term is usually understood. It is based on the more modest objective of reconciliation on the facts, because that is the irreducible basis for any other form of reconciliation or mutual understanding between victims, perpetrators and communities alike. The TRP also acknowledges that many people have occupied more than one of these roles; in addition, it allows miscarriages of justice involving some former combatants to be addressed and, by extension, helps redress further injustices inflicted on victims and survivors as a result.

Without the TRP, looking back at the recent Troubles will become a similar experience to making sense of the current centenaries, in which historians, journalists, documentary-makers and families struggle to assemble a coherent mosaic from the fragments left behind. The process is proposing an alternative route to the ‘truth’, which is different from that arrived at in the courts, where legacy wars are usually fought and which tend to perpetuate conflict rather than resolve it. The constant revisions and dilution of the law that result from these cases sometimes do more to damage the justice system than to ameliorate the effects of the conflict in the community.

As Fintan O’Toole described it bluntly in the Irish Times (16 June 2020), the process is ‘a hard-headed exchange: truth for amnesty’. It proposes the establishment of an extrajudicial process overseen by senior judges from both jurisdictions, because the conflict affected all parts of these islands. It would be staffed by civilians and would administer amnesties to former combatants willing to come forward with information for victims and survivors of the conflict.

Above: An early edition of Dan Breen’s My fight for Irish freedom—‘Would figures such as Tom Barry, Dan Breen or Ernie O’Malley have written the books they did if they knew that they would have to engage with those at the receiving end of their activities or with grieving kin?’

The key condition is that these former combatants would commit to engaging with those affected by their actions, if the latter so desire. At present, the longest sentence facing anyone convicted of murder—be it a one-off killing or multiple deaths—for most of the period covered by the Belfast Good Friday Agreement is two years, and the secretary of state for Northern Ireland has discretionary power to release anyone convicted earlier. In many ways, the ‘hard-headed exchange’ of ‘truth for amnesty’ might be seen to provide all concerned with more justice than the formal legal system.

Any interaction between former combatants and victims/survivors would be mediated by trained staff and the details would be thoroughly investigated by Reconciliation Commission investigators, who would be trained civilian researchers. Police officers would not be involved, because their job is to investigate crimes with a focus on identifying prime suspects and assembling information for a prosecution rather than situating an event in its fullest historical context.

Although former combatants would be obliged to make full disclosure of their involvement in a particular incident or incidents, they would not be required to incriminate anyone else and, if they did so inadvertently, that information could not be used to prosecute others. They could also come forward as a group if they chose. This would allow for fuller disclosure. Public disclosure of the facts could only be by mutual consent between former combatants and victims, in which case participants might wish to become advocates for the process.

It would be up to the mediation officers to make a judgement on whether and how former combatants and surviving victims and their families might interact with each other. In some cases they might never meet; in others they might reach reconciliation not only on the facts but also in a fuller sense.

Unlike the criminal justice system, this process allows for a more meaningful understanding of what happened than any cross-examination of witnesses in a court of law or public inquiry. It also allows for the possibility of contrition, repentance, atonement and, on the other side, possibly forgiveness.

For some people there will never be reconciliation. Many former combatants will never doubt that their actions were justified, regardless of the consequences, whether they are republicans, loyalists, soldiers or police officers. Similarly, some victims and survivors will never accept anything less than retribution in the fullest form available. This process is not for them.

For others, the process provides an opportunity to achieve a greater understanding of what happened and how the conflict affected others, and to learn more about themselves. No courtroom, politicians, books, archives or documentaries can do that.

Padraig Yeates is a journalist and historian involved in drafting the Truth Recovery Process.

https://www.truthrecoveryprocess.ie/