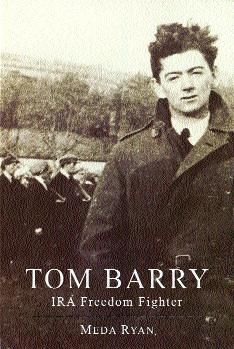

Tom Barry

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 3 (Autumn 2004), Letters, Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 12Sir,

—Further to Liam Ó Ruairc’s review of my Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter (HI 12.1, Spring 2004), Brian Hanley has raised points (HI 12.2, Summer 2004) that need clarification.

—Further to Liam Ó Ruairc’s review of my Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter (HI 12.1, Spring 2004), Brian Hanley has raised points (HI 12.2, Summer 2004) that need clarification.

I have found no evidence that Tom Barry left the IRA in 1923. On 11 July 1923, Barry wrote to the chairman of the executive council to accept his resignation ‘from the army executive council, army council and as an officer of the IRA . . .’ because of a ‘peace-feeler’ rumour circulating, plus the destruction of arms issue. Barry only resigned the organisation’s leadership in 1923. He again participated in a leadership role either in the late 1920s or early 1930s. Documents confirm that he continued as an IRA member after 1923. He wrote that he ‘publicly walked out of the IRA convention of 1938 over the passing of a resolution to start a bombing campaign [in Britain] inspired and financed by the Nazi German band of the USA’.

(1) A friendly relationship appears to have existed between Barry and chief-of-staff Frank Aiken following his resignation. In October 1923 he outlined for Aiken methods he had begun to implement in West Cork ‘to bring pressure to bear on the Staters for the release of jailed men who were on hunger strike’—the majority of whom, he wrote, ‘will stick it and that will mean the deaths of most of our very best in jail’. He was adamant that the hunger strike begged a government response. Failing this ‘we will have to fight again and next time the gloves will be off. At least mine will be. I had not them off in the last campaign.’ He maintained that it was ‘the duty of every Volunteer to co-operate’, as ‘the fight in the jails looks as if it will be the most important yet fought’.

In November 1923 Barry turned down Aiken’s offer of the position as deputy chief-of-staff, because he felt he ‘would be doing an injustice to the organisation in general by taking on work’ he didn’t ‘feel equal to’. Aiken expressed disappointment and suggested that he should be ‘definitely attached to Cork No. 2 Brigade’.

In January 1925 Barry defended Deasy in his IRA court-martial, and later at a general army convention and in a move for unity Barry urged a time limit for an attack on the north. His foremost proposal at army conventions and debates could be summed up in his views to Dr P. McCartan (1927) regarding the IRA and co-operation with other republican bodies—to achieve ‘unity in Ireland for the cause of Ireland’.

(2) In early 1923 Archbishop Harty of Cashel made a proposal for the cessation of hostilities. Then Fr Tom Duggan, with some priests and lay people anxious to heal Civil War divisions, approached Tom Barry to circulate ‘the request’ to ‘IRA leaders . . . in the interests of the future of Ireland’. Barry, in a letter to the press, stated that he felt in duty bound not to influence, but to pass on ‘the request’. (The army executive rejected the proposal.)

Shortly after the implementation of the cease-fire, derogatory rumours circulated regarding Barry’s role in these ‘peace feelers’. On 9 May he expressed his annoyance, in a letter to Mary MacSwiney, regarding rumours that he was personally in negotiation with ‘Free State people’. He maintained that he acted only as a courier. ‘I have not troubled to refute those falsehoods to any except a few who matter and I number you amongst those.’ He would only agree to ‘a negotiated peace’ on the sovereign rights of the nation being derived from the people of Ireland and told her to ‘believe that whilst the struggle for the Republic is going on’ he would not be ‘one of those who will drop out’.

In his letter of resignation from IRA leadership he stated that ‘rumours propagated in some cases by Republicans as to my negotiating for peace with the Free State, are absolutely false. Lies, suspicions and distrust are broadcasted . . .’. Being ‘suspected of compromising’ his position, he had no option, he said, but to remove himself from the executive.

(3) Barry was incorrectly blamed for informing the Free State government that the army executive was contemplating ‘a general laying down of arms’, because the Free State already had these details from a notebook that was found on the captured Austin Stack. (Stack was making his escape after the death of Liam Lynch.) The notebook contained details of ‘a draft of a memorandum, prepared for signature by all available members’, and also for arms to be handed in ‘pending the election of a government, the free choice of the people’.

The issue of negotiating with Free State personnel was to resurface in 1936 when Barry was in jail. On 13 May, Frank Aiken, minister for defence, attended a ceilí in Dundalk. Because of government policy against the IRA, the audience was in a militant mood. As Aiken took the stage, there were shouts of ‘Up Tom Barry!’ and ‘Remember the 77!’ Aiken’s voice was drowned by the audience when he said that while ‘the IRA were fighting and men were being executed, Tom Barry was running around the country trying to make peace’. Over the weeks ahead both Barry and Aiken fought out the issues in the newspapers, with former IRA comrades coming to Barry’s defence.

(4) After the ‘cease-fire dump-arms’ deal (April 1923), Barry called for the destruction of arms as a gesture to ease the plight of prisoners awaiting execution. There were ‘20,000 Republicans in jails, whilst only a few hundred men were left in arms throughout the country’, he wrote later. ‘Added to this 78 of our soldiers had already been executed and further batches were awaiting their legal murder, having already been notified.’ Arms could be replaced, he argued, but this inhuman treatment of prisoners went against all his beliefs of the code of war, hence his reasoning for the destruction of arms, to be negotiated as a bargaining ploy with the Free State.

(5) While Barry was critical of aspects of the Provisional IRA’s actions (especially the bombing of civilian targets) during the 1970s, he supported their objective. In 1970, at Kilmichael, he said, ‘the ending of partition is the responsibility of not alone the people of Ireland, but of every Irishman wherever he may be’, the objective being ‘the same as 50 years previously’. In July 1971, at Crossbarry, he again referred to the Six Counties and the support for Republicans there. A few nights after Bloody Sunday (January 1972), at an organised meeting in City Hall, Cork, Barry was the principal speaker. Thousands packed the hall, the overflow stretched over the Lee Bridge, while Republican men from each decade, the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, up to the 1970s, stood on the stage. The Provisional IRA came to him for advice on numerous occasions, but he always stressed that their targets should be military only. In 1973 Cork signatures for prisoners’ rights in the north that he had organised were ‘blocked somewhere’, he told Sighle Humphreys. In 1976 he wouldn’t attend a meeting in Dublin that Sighle was organising, as his wife, Leslie, was very ill; moreover, when he had visited the north (as mentioned to me in interview) his efforts at ‘unity’ of the republican movement were unsuccessful. Some time later (not dated) a 25-minute phone call with Sighle Humphreys who was seeking the inclusion of his name for the H-block hunger-strikers’ protest yielded a negative response because of aspects of Provisional IRA actions. Yet in 1980 at Crossbarry (shortly before his death), prior to allowing the IRA veterans to disperse, he concluded:

‘I don’t want you to fall out until the same prayers are said for men who are being crucified in H-block, Long Kesh. I want you to say prayers for them to show our unity with these men, many of whom are completely innocent and are rail-roaded by the same British that killed these men whom we are commemorating.’

—Yours etc.,

MEDA RYAN

Ennis

Co. Clare