Thomas Holand – Richard II’s King of Ireland?

Published in Features, Issue 1 (Spring 2003), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 11In June 1541 King Henry VIII began to style himself ‘king of Ireland’, abandoning the title of ‘lord’ which English kings had used for four centuries. It has long been assumed that the English kings from Henry II to Henry VII were content to rule Ireland as lords, but the events of the later years of the reign of Richard II show that this may not have been the case. In order to understand the significance of Richard’s designs for Ireland in the 1390s, it is first necessary to consider the origins of English overlordship.

‘Lords of Ireland’

In 1155 Henry II received the bull Laudabiliter from Pope Adrian IV—the first and only English occupant of Peter’s chair—mandating him to assert his overlordship in Ireland, in the cause of bringing its eccentric church customs into line with those of the Latin west. By way of encouragement in this enterprise, Adrian also sent Henry an emerald ring for the investiture of Ireland’s putative conqueror. However, Henry was a reluctant conqueror, and both papal bull and emerald ring lay unused for sixteen years, until the dramatic polarisation in Irish politics caused by the stormy career of Dermot Macmurrough, king of Leinster. Henry II’s alarm at the violence raging in Ireland in the late 1160s was heightened by the role of some of his own subjects, especially a group of Anglo-Norman adventurers, headed by Richard de Clare (the famous ‘Strongbow’), who had been recruited by Dermot to aid him in his wars against Rory O’Connor, king of Connacht.

Henry II’s great expedition of 1171–2 did much to lay the foundations of English domination, but the question of the nature of the royal title remained a matter of ambiguity.

Although popularly referred to as ‘the coronation portrait’, this was in fact painted c. 1395, when Richard II adopted the invented armorial bearings of Edward the Confessor as his own. (Westminster Hall)

Henry may have long cherished the addition of ‘king of Ireland’ to his already impressive string of dignities, and he certainly believed that this is what Adrian IV had intended. However, by the 1170s Pope Alexander III was unwilling to sanction the creation of a new kingdom, and, moreover, Ireland already had a high king (albeit a far from undisputed one) in the person of Rory O’Connor of Connacht. However, Henry was less concerned with the semantics of styling than with the realities of power, and in the Treaty of Windsor of 1175 he accepted Rory as high king of the Irish, but as his own sub-king—a title contingent on his good behaviour. When Henry’s son John, the future king, was sent to Ireland at his father’s expense in 1185, he went as ‘lord of Ireland’. Thus until 1541 the kings of England were, by ‘the grace of God’ and by the terminological imprecision of Adrian IV, ‘lords of Ireland’.

However, the failure of the Angevins to establish a separate kingdom did not deter challengers from emulating the career of Rory O’Connor and aspiring to the high kingship of Ireland. In the 1250s Brian O’Neill proffered his own claim, but undoubtedly the most dangerous of the pretenders was Edward Bruce, brother of Robert, king of the Scots. His coronation as king of Ireland, in May 1316, inaugurated a reign of fratricidal and murderous violence which came to an abrupt end at Dundalk, the very place of his coronation, on 14 October 1318. In 1374 O’Brien of Thomond attempted to resurrect the high kingship in his own person, but the claim came to nothing.

More active English royal engagement

However, the second half of the fourteenth century heralded a more active English royal engagement in Ireland. In 1361 Edward III had sent his second son, Lionel, to govern Ireland as his lieutenant. Married to Elizabeth, heiress of the defunct de Burgh earls of Ulster, Lionel transmitted his father’s authority both through the official channels of the Dublin bureaucracy and through his wife’s kinship networks until his death in 1369. Whereas Edward, prince of Wales, had been advanced from duke to prince of Aquitaine, his brother Lionel had remained duke of Clarence and earl of Ulster. Also, there is no indication that Edward III considered alienating the lordship of Ireland to his son.

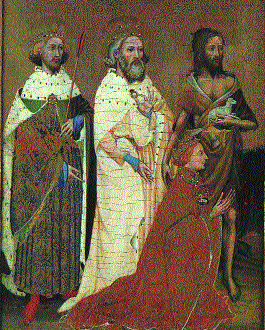

Wilton Diptych, painted c.1395–9. Richard II is depicted as a much younger man, kneeling before his three favourite saints (left to right)-St Edmund the Martyr, St Edward the Confessor and St John the Baptist.

After Lionel’s death the earldom of Ulster and the lieutenancy passed into the hands of his son-in-law, Edmund Mortimer, who held the office until his death in 1381. For the first few years of the reign of Richard II the governance of Ireland was carried on through the lieutenancy, but, owing to the extreme youth of the Mortimer heir, Earl Roger, the office was held by a succession of English noblemen and royal servants.

This suddenly changed in 1385, when Richard II created his favourite, Robert de Vere, marquess of Dublin and, in the following year, duke of Ireland. The 27-year-old de Vere was already earl of Oxford, but his landed inheritance was a woefully depleted holding in Essex, and he had no pre-existing connection with the country of which he was now not merely duke but also full palatine lord. It would seem that Richard II had decided to afford his friend (and alleged lover) the plenitude of power that Henry II had envisaged for John in 1177. Whereas Edward Bruce was destroyed by his subjects, de Vere had virtually no contact at all with the Irish, and during his brief rule he governed entirely through his appointees to Dublin bureaucracy. However, the English chronicler Thomas Walsingham—a source with a keen ear for gossip—claims that, but for the universal hatred of de Vere within the English political community, Richard II would have made a king of his duke. Quite how de Vere would have been received as king of Ireland can never be known, as he ended his days as a forfeited traitor and exile in Louvain in 1392.

The fall of Robert de Vere in 1388 marked the reversion to the conventional mechanisms of rule through the royal lieutenant, but the manner of the duke’s destruction left Richard with a lingering sense of bitterness against Ireland’s most powerful dynasty, the Mortimer earls of March and Ulster. Throughout the campaign of the lords appellant against Richard II, the Mortimer estates had been under the administration of a trust headed by the king’s most hated enemy, the earl of Arundel. The link-man between Arundel and the Mortimer connection in Wales and Ireland was Sir Thomas Mortimer, who, although an illegitimate cadet of the family, was its effective chief and steward of its estates. In November 1387 the army raised by Arundel and his friends was almost certainly funded from the revenues of the Mortimer inheritance, as the payments of cash by Thomas Mortimer can be traced in the surviving household records. In 1390 Arundel strengthened his connections with the Mortimers through his marriage to Philippa, sister of the young Earl Roger. Although Richard made no immediate move to punish his enemies once he had regained power in 1389, it is undoubtedly the case that he did not forget the involvement of the Mortimers in his humiliation and in the destruction of his friends, especially de Vere.

Richard II’s 1394 expedition to Ireland

Richard II’s expedition to Ireland in 1394 was the first by an English king since that of John in 1210. The sudden reawakening of Richard’s personal interest in Ireland is difficult to explain, as only two years previously he had considered using its lieutenancy as a means of keeping his hated uncle and recent enemy, Duke Thomas of Gloucester, away from court.

King of Leinster, Art Macmurrough (right), sallies forth to parley with Thomas, earl of Gloucester (left), Richard II’s envoy on his second (1399) Irish campaign. From the illustrated eye witness account of the campaign by Jean Creton. (British Library)

By the early 1390s the vacuum of English royal authority was such that Art Macmurrough, king of Leinster, had free rein to pursue his quarrels, and especially to erode the lordship of the young earl of Ulster, who had only recently come of age. The scale of Richard II’s intervention, at the head of at least 7000 men, and its duration, from October 1394 to May 1395, enabled him to secure the submission of the leading Irish princes, including Macmurrough himself, who at one point had been pursued into the night with only a shirt to preserve his kingly dignity. But Richard had also succeeded in achieving a significant political realignment by delivering to the Irish the disinterested justice that they could not obtain through the established judicial system dominated by the crown’s servants and the vested interests of the English nobility. A major consequence of this intervention was to marginalise the royal lieutenant, Roger Mortimer, who was doubtless counting on royal help to recover some of his family’s authority in Ulster. When Richard II set sail for England in May 1395, he left behind his friend Sir William Scrope as justiciar—as much for the surveillance of Mortimer as for the upholding of the agreements with the Irish princes.

Richard II’s fateful return to Ireland, in the late spring of 1399, has long been identified as the window of opportunity that allowed Henry of Lancaster to usurp the throne of England. By the end of 1397 Richard II had wrought vengeance upon the men who had humiliated him ten years previously. Gloucester and Arundel were dead, Warwick was imprisoned for life on the Isle of Man, and their heirs had been disinherited in perpetuity. However, the political situation in Ireland had deteriorated gravely since the expedition of 1394–5. In Ulster Niall Mor O’Neill was at war with the Mortimer earl and was clamouring for royal protection, while Art Macmurrough was making hay in the sunshine of royal absence.

Thomas Holand

But what really transformed the political situation in Ireland was Roger Mortimer’s slaying, at Kellistown, on 20 July 1398. By this time Mortimer was a marked man, and in reality he would have been little safer back in England. On 27 July, and still apparently unaware of Mortimer’s death, Richard II issued letters dismissing him from the lieutenancy of Ireland. In his place Richard appointed his nephew—and the brother of the widowed countess of March and Ulster—Thomas Holand. If we are to believe the chronicler Adam Usk, a well-connected lawyer whose Oxford education had been funded by the Mortimer family, Holand had already been sent to Ireland to arrest his brother-in-law.

The tower of Mountgrace priory, Northallerton, Yorkshire, added c.1415 by Thomas Beaufort, duke of Exeter, the second founder of the priory. Thomas Holand’s initial foundation of 1398 was intended to pray for the souls of King Richard II, Queen Isabella, Holand himself and his uncle John Holand, duke of Exeter. The three men all perished in 1400 after Henry IV’s usurpation. (Andy King)

Thomas Holand was Richard II’s nephew, the son of his half-brother, Thomas, earl of Kent, who had died in 1397. Throughout the 1380s and 1390s Richard II had been very close to his elder half-brother Thomas, whom he had appointed constable of the Tower of London. In spite of this proximity to Richard, the elder Thomas Holand had not been a political man, and by the time of his death in April 1397 he had been living a leisurely existence for many years. Even before Thomas Holand the younger had succeeded to his father’s honours in 1397, he had been marked out for royal favour. By 1395 he was already in receipt of a 200 mark annuity, enough to enable a 24-year-old to cut a reasonable dash at court. That same year the king allowed the Holand family to quarter their arms with those of his beloved saint, Edward the Confessor, a special mark of favour. But what really transformed Holand’s fortunes was Richard II’s destruction of his enemies in September 1397.

Although Holand had only recently inherited the earldom of Kent and a handsome landed inheritance worth at least £2000 annually, his support for Richard II earned him the newly created dukedom of Surrey, and one of the finest spoils of the recent royal triumph—Warwick Castle and its estates. If Richard had hoped to establish his nephew as a great power in the West Midlands, then events in Ireland completely changed his plans. From the autumn of 1398 Thomas Holand, the new lieutenant of Ireland, saw nothing more of his recently acquired English honours but started to play a role on a much larger stage. In his 1997 biography of Richard II Nigel Saul described Holand’s role as ‘an interim one’ and relegated Holand to the status of a ‘stalking horse’ for Richard himself. But a closer examination of the grants made to Holand show that Richard was planning a far more significant role for his nephew. Saul tells us that Holand was not endowed with great estates in Ireland—in fact he was entrusted with the keeping, rent-free, of all the Mortimer estates, including the lordships of Ulster and Trim, for the duration of the minority of the infant earl of March and Ulster, who would not in fact attain his majority until 1413. More significant still was the royal order of 22 January 1399 empowering Thomas Holand to accept all the homages due to the English king for the remainder of his term as lieutenant.

Traditionally, this appointment has been regarded as a forerunner to Richard II’s own return to Ireland, by which time the preparations for the crossing were well under way. Richard II landed at Waterford on 1 June 1399, and it has long been accepted that the purpose of the mission was to bring to heel those Irish princes who had broken their submissions of 1394–5. But an examination of the hitherto neglected indentures for the army of 1399 show that it numbered about 3000, less than half the size of that which he had brought with him four years before. Even more striking is the composition of the army’s leadership—three dukes (including Thomas Holand), three earls, and all five captains of the king’s bodyguard. This was a gallant company, to say the least.

Preparations for a coronation?

In his chronicle Adam Usk offered a dramatically different explanation for the expedition—that it was intended to pave the way for the coronation of Thomas Holand as king of Ireland, in the Great Hall of Dublin Castle, on 13 October 1399. Usk’s claim has long been ignored by historians, but a compelling corroboration can be found in a set of accounts in the London Public Record Office, relating to Holand’s Irish lieutenancy. On 16 May and 17 June 1399, Robert de Farrington, the treasurer of Ireland, received £139 and £40 of royal funds from Thomas Holand, described as ‘that noble prince’, ‘for the work at Dublin Castle and the great hall of the same’. On 22 May, while preparations for the royal crossing were at their height, a clerk of Thomas Holand’s called William Glyn received from the treasury a consignment of jewels, valued at £200, which his uncle, the executed earl of Arundel, had lodged with his sister, the countess of Kent, Holand’s own mother, at the time of his arrest and trial. The most striking object in the collection is a coronet, which was a famous possession of Holand’s maternal grandfather, the great financier and wool magnate earl of Arundel, who had died in 1376.

Are these the preparations for the coronation of a king of Ireland in the Great Hall of Dublin Castle? Sadly we have only these fragments of evidence, but the concordance of Usk’s claims and the financial records cannot be ignored. Of course, Thomas Holand never had his day in Dublin Castle, as news reached Richard II in early July 1399 of the landing of Henry of Lancaster, the event which precipitated the collapse of his kingship. The capture of Richard II in Wales in the middle of August 1399, and his subsequent deposition, is a well-known story, but what became of the putative king of Ireland?

Epiphany Rising débâcle

Like Richard II’s other closest allies, Thomas Holand was brought to account for his complicity in the king’s actions in the final two years of his reign. He suffered the loss of all that he had gained under Richard’s patronage since 1397, but his very considerable inherited wealth and honours, including his earldom of Kent, remained intact. Although Richard II’s other leading allies forfeited their promoted titles, Thomas Holand lost more than all of the others if his expectations in Ireland are taken into account. Perhaps this is why Thomas Holand and his uncle, John, earl of Huntingdon, were the prime movers behind the abortive re-adeption of Richard II in January 1400. The débâcle of the Epiphany Rising of 1400 sealed the fate of the captive Richard, while his chief advocates met violent deaths at the hands of ordinary Englishmen. Thomas Holand and the principal group of conspirators were lynched by the townsmen of Cirencester, where they had fled after a failed attempt to assassinate Henry IV during the New Year celebrations at Windsor Castle. Holand’s head, together those of the other leading Ricardians, was displayed on London Bridge, while his trunk was buried at Cirencester Abbey, where he had met his end. After three months of grisly display, Holand’s head was returned to his widow, Joan, for burial with his remains.

The final resting-place of Ireland’s king-who-never-was is far removed from the dramatic scenes of his meteoric rise and fall. In February 1398 Holand had been granted a licence to found a priory for the Carthusian Order at Mountgrace, beneath the Cleveland Hills, not far from the Yorkshire town of Northallerton. At Holand’s death the priory was incomplete, but by the time of his reburial there, in 1412, its buildings are likely to have been well advanced. To this day the remains of the 23 individual cells, in which the monks lived alone, can be seen at Mountgrace, although no traces of Holand’s tomb remain. Perhaps the most telling sign of the pride that his family had invested in his foundation was the remarkable water supply, fed from a nearby spring, covered with a stone building, and feeding into a dedicated water-tower in the cloister.

In the fifteenth century the English crown’s interest in Ireland waned, and royal authority was mediated through the well-established administrative channels. Although Mortimer blood flowed richly in the veins of Richard of York, the royal lieutenant in the late 1440s, no further experiments were made to alter the title of English royal overlordship until the time of Henry VIII.

Did Richard II really plan to install his nephew as king of Ireland? He was certainly not afraid to make grand gestures, and had already conferred the palatinate lordship of Ireland on an alien in 1385. In 1397 he made a principality of his favourite county of Chester, and endowed it with the trappings of a high steward and constable, and even its own herald. An investiture in the Great Hall of Dublin Castle would have satisfied his tastes for political ceremony and drama, and would have been a grand culmination to his second expedition of 1399, much as the princes’ submissions had been four years before. Whatever the exact nature of Richard’s plans, the vanished tomb at Mountgrace Priory once held the remains of a man whose political destiny had lain far to the west.

Alastair Dunn is Research Associate at the Department of History, University of Durham.

Further reading:

R.R. Davies, The first English empire, 1093–1343 (Oxford, 2000).

R. Frame, The political development of the British Isles, 1100–1400 (Oxford, 1989).

J. Lydon, The English in medieval Ireland (Dublin, 1984).

N. Saul, Richard II (Yale, 1997).