Theatre Eye

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, General, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2008), Reviews, Volume 16

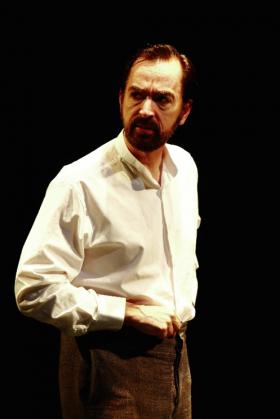

Sir Roger Casement (Philip Goodwin)—his life and legacy are shrouded in paradox, controversy and conspiracy.

Prisoner of the Crown

Richard Stockton

Irish Repertory Theatre, 132 West 22nd Street, New York, May–July 2008

by Mark Coalter

The life and legacy of Roger Casement are shrouded in paradox, controversy and conspiracy. As a liberal Edwardian figure, Casement was a celebrated British diplomat who was knighted by George V for his courageous humanitarian services in Africa and South America. Conversely, he became—despite an Ulster Protestant upbringing—an Irish nationalist, readily embracing the armed struggle against British rule. Yet when returning to Ireland in April 1916 on board a German submarine, after his unsuccessful attempt to raise an Irish brigade in prisoner-of-war camps, it was to persuade Pearse and Connolly to stop the Easter Rising, thereby averting unnecessary bloodshed. Finally, as an Irish martyr, who died for the cause and was received into the Catholic Church prior to his execution, he found his name muddied by the British government’s sanctioned distribution of extracts from his ‘black diaries’ to opinion-formers on both sides of the Atlantic.

Paradox has induced controversy and conspiracy. This receives ample coverage in Prisoner of the Crown by Richard Stockton, which first opened at the Abbey in 1972 and recently played in the Irish Repertory Theatre in New York. The play concentrates on the period from Casement’s capture near Banna Strand, Co. Kerry, his subsequent incarceration in the Tower of London and his trial for treason, culminating in his execution. Running parallel with the courtroom drama are the deliberations of the jury and the machinations of the government and its surrogates. Dramatising historical events can be a minefield, when even the most minor of omissions can offend the purists. What are we therefore to make of Prisoner, which plays rather hard and fast with the facts? As a dramatic interpretation it works, and effectively conveys the traditional view of Casement as the innocent victim of base British skullduggery and realpolitik. From a historical perspective, however, it should carry a significant health warning.

Casting a shadow over the action in Prisoner are the ‘black diaries’, which, 92 years on, still excite debate. Stockton highlights the British dilemma of executing Casement so soon after the leaders of the Easter Rising had been similarly dispatched. As Sir Frederick Smith, attorney general and formerly ‘Galloper’ Smith—a sobriquet earned through service in Ulster to Sir Edward Carson—comments to Reginald Hall, of British Intelligence, the evidence is

‘good enough to convict [but] not good enough to annihilate. Despite centuries of evidence to the contrary, the Crown never meant to go into the business of manufacturing Irish martyrs.’

![Attorney General F. E. Smith (John Windsor-Cunningham, left) comments to Sir Reginald Hall of British intelligence (John C. Vennema, right) that the evidence is ‘good enough to convict [but] not good enough to annihilate’.](/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/69_small_1247638032.jpg)

Attorney General F. E. Smith (John Windsor-Cunningham, left) comments to Sir Reginald Hall of British intelligence (John C. Vennema, right) that the evidence is ‘good enough to convict [but] not good enough to annihilate’.

Stockton’s depiction of the jury’s deliberations is powerful, although in all likelihood historical fantasy. In Prisoner the English jury members, all largely prejudiced and infused with jingoism, quote liberally from the diaries—here, they have even been provided with the juiciest extracts—as a way of persuading the one dissenting voice, incidentally played by the same actor cast as Casement. One juror comments that Casement’s diary ‘proves that he has been addicted for years to the most loathsome and bestial sodomitical practices’, and while this does not sway the waverer, it is, coupled with some unpardonable verbal bullying, enough to make him more pliable and convinced of the merits of a guilty verdict.

In respect of the courtroom drama itself, Stockton makes Casement’s homosexuality fair game for the prosecution. Smith’s excessive use of innuendo is largely at odds with the record. When asked to clarify what is actually meant by his words, Smith responds: ‘I have always tried to speak only the best Queen’s English’. This no doubt conforms with Stockton’s view of the depths to which the future lord chancellor was willing to stoop, although in reality such a line would likely have been rather obvious and vulgar for F.E.’s tastes. In the final scene Smith and a member of the prosecution team remove the box from under Casement’s feet after the noose has been placed around the prisoner’s neck, a clever and symbolic device utilised by Stockton to place ultimate responsibility at the door of the Crown.

Casement confides in his favourite cousin, Gertrude Bannister (Emma O’Donnell). She was adamant that Casement was not homosexual and that the ‘black diaries’ were forged.

(All images: Carol Rosegg)

Stockton’s characterisations are mostly solid, although a little inadequate in part. Philip Goodwin plays a taciturn Casement, a patriot rising above the mud-slinging of the British establishment, disorientated by his captivity but nobly awaiting whatever fate decrees. On the other hand, Smith’s portrayal is rather underwhelming. This probably has more to do with the play itself than with any deficiency in casting. The conspiratorial elements may be strong, but Smith’s legendary wit and domineering personality are practically non-existent. Surprisingly, Stockton does not include Smith’s abrupt and petulant exit during Casement’s final statement, which might have made ‘good theatre’ and has the advantage of actually having occurred!

Casement has been the subject of academic and popular reappraisal in the past decade. The ‘black diaries’ still provoke controversy, but, thankfully, there has also been renewed interest in his humanitarian contribution. Although Prisoner is historically questionable in parts, it does reintroduce Sir Roger to modern audiences, who, while finding the play tragic, amusing and perhaps slightly clichéd, will be spurred on to delve further into the man and the period.

Mark Coalter is a writer and researcher based in New York.