‘The Widow’s Mite’: private relief during the Great Famine

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 2 (Mar/Apr 2008), The Famine, Volume 16

The Eviction, by Erskine Nicol, 1853. (National Gallery of Ireland)

During earlier food shortages in Ireland, including in 1822 and 1831, charitable bodies had been set up to provide relief at a local level, and some of these were revived following the first failure of the potato crop in 1845. But after 1846 donations came from all over the world, even from people who had no connection with Ireland. This help cut across religious, national and economic differences. It came from people who were themselves poor, including former slaves in the Caribbean, Native Americans and prisoners in Britain. Heads of states were also involved—Queen Victoria, the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and the president of the United States. Extensive fund-raising was carried out in Ireland by all sections of society. Resident landlords were generally involved, although many absentees were criticised for their indifference. Even children raised funds: for example, pupils in a school in Armagh City collected for the local poor in 1847.

Fund-raising in Ireland

In folk memory, Irish landlords generally have been condemned for their callous attitude towards their poor tenants. In fact, the response varied; while some used the distress to evict their tenants, others gave relief in different ways. When the blight came a second time, some landlords lowered their rents by ten per cent. These actions tended to be short-term, especially because landowners themselves had financial problems when rates (local taxes) rose steeply and income from rents fell.

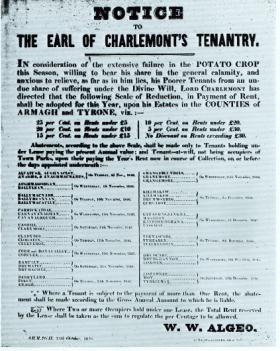

Rent abatement notice in 1846 from the earl of Charlemont to his tenants in counties Armagh and Tyrone. In folk memory, Irish landlords generally have been condemned for their callous attitude. In fact, the response varied; while some used the distress to evict their tenants, others gave relief in different ways, often in the form of rent abatements, as here. (National Library of Ireland)

Most of the charitable efforts of Irish landlords were concentrated on the early months of 1847. The marquis of Sligo, a liberal landlord, was chairman of a committee that set up a private soup kitchen in Westport in January 1847. He made an initial donation of £100 and promised a subscription of £5 per week. Other local gentry and Church of Ireland clergy contributed, and the opening fund reached £255. In County Down Lord Roden, a landlord known for his evangelical views and his involvement in the Orange Order, opened a soup shop on his estate where soup, made of rice and meal porridge, was sold at a penny a quart and potato cake cost a penny for 12oz. Some landlords, such as the earl of Shannon, also resold soup at less than cost. In Skibbereen, which became infamous for the sufferings of its people, the Church of Ireland minister, Revd Caulfield, was giving 1,149 people one free pint of soup each day. In Belfast a privately funded relief committee in Ballymacarrett gave soup to over 12,000 people daily, about 60 per cent of the local (predominantly Protestant) population. On some estates rent was reduced or employment provided. Daniel O’Connell reduced rents on his County Kerry property by 50 per cent. Lord and Lady Waterford financed a soup kitchen on their estate, and Maria Edgeworth in Edgeworthstown provided free seed to her tenants. The earl of Devon sent £2,000 and the duke of Devonshire £100 to help their tenants. But not all landlords were generous. The absentee landlord James Robinson donated only £1 to the Waterford Union for its soup kitchen. Lord Londonderry, one of the ten richest men in the United Kingdom, who owned land in counties Down, Derry, Donegal and Antrim in addition to property in Britain, was criticised for his meanness: he and his wife gave £30 to the local relief committee but spent £150,000 renovating their Irish home.

Society of Friends (Quakers)

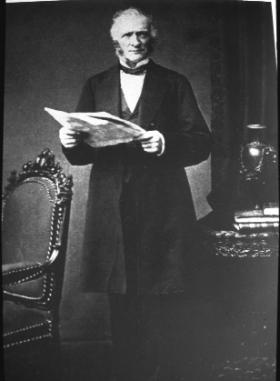

The Famine attracted assistance from a wide variety of religions, ranging from Hindus in India to Jews and Baptists in New York. While the main Protestant churches (Church of Ireland and Presbyterian) were actively involved in collecting and distributing relief, the Society of Friends (Quakers) distinguished itself. The efforts of Irish and English Quakers such as Jonathan Pim and James Hack Tuke to organise relief works were widely praised. Jonathan Pim and his brother William Harvey Pim were Dublin drapers and textile-manufacturers. The former later became Liberal MP for Dublin, the first Irish Quaker to sit in parliament. James Hack Tuke, an English banker, was very active in relief distribution in 1847 and again in 1880.

In November 1846, at the suggestion of Joseph Bewley, the Central Relief Committee of the Society of Friends was established in Dublin. The Bewleys were tea and coffee merchants who went on to found their well-known Oriental cafes in Dublin and elsewhere. During the Famine Bewley was joint secretary with Jonathan Pim of the Central Relief Committee. In the following month a sister committee was set up in London. Both agencies worked closely with their co-religionists in the United States. Though the Quakers in Ireland were small in number (c. 3,000), they played a most important role in providing relief, particularly through soup kitchens. When the government decided to use soup kitchens as the main form of relief in the spring of 1847, the Quakers provided the boilers and cauldrons.

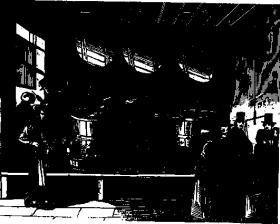

By January 1847 this Society of Friends soup kitchen in Cork was distributing 6,800 litres daily. (Illustrated London News, 16 January 1847)

The Quakers were particularly effective in informing newspapers in Dublin and Britain of the true situation in the west of Ireland, emphasising the extent of suffering. At the beginning of 1847 the Committee warned that unless more food was made available millions of lives would be lost, adding that ‘those who are guilty of neglect in these particulars will be responsible before man, and we venture to add, before an all-just Providence’.

The Quakers were also successful in raising money outside Ireland. And, unlike many other charitable bodies, their involvement did not end in 1847. Working with local Protestant and Catholic clergymen, they distributed almost 2,000 individual grants ranging from £10 to £400. The largest grants, over £20,000, were made in Connacht, although over £11,000 was donated to Ulster, principally Cavan and Donegal. At the end of 1847, as donations dwindled, the Committee wound down its activities. It did not accept (as the government did) that the Famine was over, but it felt that charity towards Ireland had dried up. The Quakers decided that, instead of giving direct relief to the poor, they would concentrate on providing longer-term assistance by supplying fishing tackle, seeds and farm implements. In response to the deepening distress after the harvest failure in 1848, particularly in the south and west, the British government asked the Quakers to resume their relief work. They refused to do so, believing that the situation was so desperate that only the government had the means to resolve it.

Quakers themselves were personally involved in distributing famine relief, and this took its toll. At least fifteen Quakers died as a result of famine-related diseases. Jonathan Pim collapsed from overwork, and the premature deaths of Joseph Bewley, Jacob Harvey and William Todhunter were blamed on exhaustion. Undoubtedly, though, their hard work had saved thousands of lives. In the period of a year the Quakers had distributed approximately £200,000. Their work was particularly important because it was direct, was based in the communities where it was required, and had no ideological or religious strings.

Catholic Church

The larger churches played an important part in the distribution of government and private relief. Local priests and ministers were widely praised for their role in helping the poor. Some established their own relief committees to raise funds. The two Catholic bishops who were particularly involved were Archbishop Murray of Dublin and Archbishop MacHale of Tuam. Catholic aid continued beyond 1847, when many other forms of private relief had ceased. The amount collected is hard to quantify but it was probably more than £400,000, which was distributed by local priests, thus avoiding much of the expense and delay that marked government relief.

Jonathan Pim, joint secretary of the Central Relief Committee of the Society of Friends. He later collapsed from overwork. (Friends Historical Library)

The Irish Catholic Church used its overseas network to attract donations. Some of the largest amounts were raised by Catholic parishes in Britain and the United States. The Tablet, the leading English Catholic newspaper, offered to act as a channel for English Catholics to send money. By March 1847 Bishop Fitzpatrick in Boston had raised almost $20,000, mostly from local Catholics, though it was meant for distribution to all creeds in Ireland. The staff and students of Maynooth College made a donation of over £200.

A committee for the Irish poor was established in Rome on 13 January 1847. Pope Pius IX donated 1,000 Roman crowns from his own pocket. In addition to personal financial assistance, he offered spiritual and practical support. In March 1847 he took the unprecedented step of issuing a papal encyclical to the international Catholic community, appealing for support for the victims of the Famine. As a result, large sums of money were raised by Catholic congregations: the Vincent de Paul Society in France raised £5,000; the diocese of Strasbourg collected 23,365 francs; two priests in Caracas in Venezuela contributed £177; Father Fahy in Argentina sent over £600; a priest in Grahamstown, South Africa, donated £70; and the Catholic community in Sydney, New South Wales, sent £1,500. Despite the unique intervention by Pope Pius IX, the Irish bishops failed to thank him for his donation or for the encyclical letter until forced to do so by Dr Paul Cullen. Cardinal Fransoni, an adviser to the pope, even accused the Irish bishops of laziness in fund-raising for the poor, even though he had given them official permission to do whatever needed to be done. The thanklessness of the Irish bishops and their wrangling with one another lost them further vital support in Rome. The pope’s concern and support for Ireland came to an abrupt end in 1848, when the revolutionary struggle in Italy forced him to flee Rome. Nevertheless, his brief interest had a major effect in encouraging the international Catholic community to support relief in Ireland. But things could be difficult. As the experience of the bishop of Augsburg demonstrated, transferring money to Ireland could be complicated.

Women

Women, who were generally invisible in public affairs, were particularly involved in the collection and distribution of private relief. They were encouraged by the early action of Queen Victoria, who donated £2,000 to the British Relief Association in January 1847. This made her the largest single donor to famine relief. More importantly, Victoria published two ‘Queen’s Letters’, the first in March 1847 and the second in October 1847, asking people in Britain to donate money to relieve Irish distress. The first was printed in the main newspapers and read out in Anglican churches. Following its publication, a proclamation announced that 24 March 1847 had been chosen as a day for a ‘General Fast and Humiliation before Almighty God’, and the proceeds were to be distributed to Ireland and Scotland. The queen’s first letter raised £170,571, but the second raised only £30,167. In fact, the second letter was widely condemned in Britain, indicating a hardening in public attitudes towards the giving of private relief to Ireland.

Queen Victoria, pilloried in folk memory as the ‘Famine Queen’ who only donated £5 in famine relief, in fact donated £2,000 to the British Relief Association in January 1847, making her the largest single donor. (Multitext Project)

Following the second appearance of the blight in 1846, associations such as the Ladies’ Relief Association in Dublin and the Belfast Ladies’ Association were formed. The Society of Friends also established separate ladies’ committees. One of the most successful of the women’s groups was the Belfast Ladies’ Association, which first met on 1 January 1847. The oldest member was Mary Ann McCracken, sister of Henry Joy, executed as a rebel in 1798. Initially the Association was formed for the relief of distressed districts in the west of the country, but increasingly it became clear that there was famine elsewhere, even in industrial towns such as Belfast, and so their involvement became nationwide. Apart from food and clothes, they provided poor women with wool and flax to enable them to work. This Committee refused to proselytise, that is, convert poor Catholics to Protestantism in exchange for relief.

Some ladies’ groups did proselytise, however, including the Belfast Ladies’ Association for Connaught. They wanted to counteract the effects of the famine in the west of Ireland by trying to ‘improve, by industry, the temporal condition of the poor of the females of Connaught and their spiritual [condition] by the truth of the Bible’. These aims had support from both evangelical clergy and politicians. By 1849 the Association had collected £15,000 and established industrial schools in ‘wild Connaught’, where skills such as knitting and needlework were taught. By 1850, 32 schoolmistresses were employed within the province, who worked under the direction of the resident ladies. In the same year the Association claimed to have offered employment and education to over 2,000 poor girls and women. Its members tried to change the habits and morality of the poor in general by influencing the behaviour of women.

An extraordinary range of activity was undertaken by women of all denominations. Food kitchens were set up; women organised the distribution of relief and collected money; nuns nursed in fever hospitals and fed the starving at their convents. Women tried practical solutions to poverty by creating employment for the female poor in cottage industries. Generally, this work depended on the enthusiasm of individuals. Needlework became an integral part of the education given by nuns to poor children, and many laywomen acted as teachers and benefactors in schools where needlework was taught. Similar work was carried out by the Ladies’ Industrial Society of Ireland, founded at the height of the Famine in 1847 to ‘carry out a system for encouraging and developing the latent capacities of the poor of Ireland’. Other smaller ladies’ committees were formed, such as the Newry Benevolent Female Working Society, which provided employment for women in spinning, knitting and needlework.

The United States and worldwide

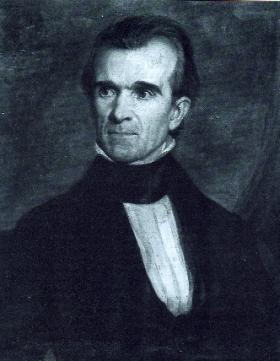

US President James Polk made a $50 donation: a Boston newspaper declared scornfully that it was too small and had to be ‘squeezed’ out of him. (Tennessee Historical Society)

The United States, which had strong connections with Ireland, provided very significant private relief—in excess of $2,000,000. A large part was in the form of cash, food, clothing and blankets. One of the first relief committees was established in Boston at the end of 1845, although most of the relief efforts came after the second failure of the potato crop. The Boston committee, which included many members of the local Repeal Association, blamed the Famine on British misrule. There was a more widespread response to the second potato failure, helped by the fact that the United States had enjoyed a bumper harvest. An attempt was even made by the US Senate to provide $500,000 for Irish relief, though it ultimately failed. Nonetheless, in 1847, members of the American government, including the vice-president, George Dallas, were giving assistance to Ireland. The president, James Polk, made a $50 donation: a Boston newspaper declared scornfully that it was too small and had to be ‘squeezed’ out of him.

By January 1847 the payments totalled over a million dollars. One action of the relief committees in Boston that received great publicity was the sending of two ships (the Jamestown and the Macedonian) full of supplies to Cork in 1847. The Jamestown completed the journey to Cobh in record time. A portion of the food on the Macedonian was distributed in Scotland. Both ships were manned by volunteers. The fact that the United States was in the middle of a war with Mexico made its government’s granting of permission more noteworthy. In reply to criticisms for permitting a US warship to be used for the benefit of another country, Captain Forbes of the Jamestown declared that ‘it is not an everyday matter to see a nation starving’. A Boston newspaper described the mission of the Jamestown as ‘one of the most sublime transactions in the nation’s history’. Some Cork newspapers used the arrival of the Jamestown to contrast the generosity of the United States with the meanness of the British government. In total, over 100 vessels carrying 20,000 tons of foodstuffs came from the United States to Ireland in the wake of the Jamestown.

Although many high-ranking officials became involved in relief, donations came, too, from people who were themselves poor and disadvantaged, such as the Choctaw Indians in Oklahoma. Their contribution of $170 was made through the American Society of Friends. Prisoners in Sing Sing Jail also made a donation. Jacob Harvey, who coordinated relief donations in New York, estimated that in January and February 1846, Irish labourers and servants had sent $326,410 to Ireland in small bank drafts.

Assistance came from unexpected places. The first Famine subscription had been raised in India at the end of 1845, on the initiative of British troops serving in Calcutta. It was followed by the formation of the Indian Relief Fund in January 1846, which appealed to British people living in India to start similar collections. They raised almost £14,000. The Freemasons of India contributed £5,000. A contribution of £3,000 was raised in Bombay in one week. The government of Barbados gave a donation, partly inspired by one received from Ireland some years earlier. In 1847–8, committees in Australia raised over £10,000. Money was set aside to assist emigration from Ireland to Australia, but was eventually returned to the donors because the committee could not agree about the kind of emigrants to help, whether paupers or able-bodied emigrants. Other donations came from South Africa (£550), St Petersburg, Russia (£2,644), Constantinople (£620), the islands of Seychelles and Rodrigues (£111 and £16) and Mexico (£652). This shows that the Famine had become an event of international significance.

‘Souperism’

The USS Macedonian arrived at Cork with food aid from New York in summer 1847. Local newspapers used the occasion to contrast the generosity of the United States with the meanness of the British government. (Illustrated London News, 7 August 1847)

Private charities provided essential relief, but the activities of a few were controversial, especially where they were associated with proselytism. In the genuine belief that they were saving souls, a small number of Protestant evangelicals used the hunger of Catholics as a means to convert them. The converts were given disparaging names: ‘soupers’, ‘jumpers’ or ‘perverts’. A few charitable bodies read the Bible to the poor to whom they gave food. In the west of Ireland, famine missionaries, such as the evangelicals Revd Hyacinth Talbot D’Arcy and Revd Edward Nangle, tried to win converts in this way. Some evangelicals believed that the British government had caused the Famine by giving a grant to Maynooth College in 1845 to train priests: ‘It is done, and in that very year, that very month, the land is smitten, the earth is blighted, famine begins, and is followed by plague, pestilence and blood’.

Another well-known missionary who worked in the west of Ireland was Michael Brannigan, a convert from Catholicism to Presbyterianism and a fluent Irish-speaker. In 1847 he established twelve schools in counties Mayo and Sligo, and by the end of 1848 the number had grown to 28, despite ‘priestly opposition’. Attendance dropped when the British Relief Association began providing each child with a half-pound of corn-meal every day, but this ended on 15 August 1848 when funds ran out.

The worries of the Catholic Church are well put in a letter from Fr William Flannelly of Ballinakill, Co. Galway, to Daniel Murray, archbishop of Dublin, on 6 April 1849:

‘It cannot be wondered if a starving people would be perverted in shoals, especially as they [the missionaries] go from cabin to cabin, and when they find the inmates naked and starved to death, they proffer food, money and raiment, on the express condition of becoming members of their conventicles.’

The Freeman’s Journal condemned this as ‘nefarious unchristian wickedness’. The pope felt worried enough to urge the Catholic hierarchy to oppose the work of missionaries and, on one occasion, he reprimanded the bishops for not doing enough to protect their flocks.

By 1851 the main missions claimed that they had won 35,000 converts and they were anxious to win more. Shortly afterwards, 100 additional preachers were sent to Ireland by the Protestant Alliance. Well-provisioned missionary settlements in such destitute areas as Dingle and Achill Island attracted many converts. The missions were generally opposed by the Church of Ireland, but their impact was, in the end, slight and tended to be localised. Some charitable organisations (including orders of nuns) believed that the distress gave them an opportunity to teach the Irish peasantry ‘good’ habits of hard work. The missions, and the illiberal reaction of the Catholic clergy, tended to encourage sectarianism. Besides, many converts had to go elsewhere because of hostility and contempt in their own communities.

Most private donations and charitable bodies came to an end at the harvest of 1847, partly because donations had started to dry up but also because the blight had not appeared in 1847 and people believed the Famine was over. Though private charity was short-lived, it played a vital role in saving lives.

Christine Kinealy is Professor of History at Drew University, USA.

Further reading:

R. Goodbody, A suitable channel: Quaker relief in the Great Famine (Dublin, 1992).

D. A. Kerr, The Catholic Church and the Famine (Dublin, 1996).

C. Kinealy, This great calamity. The Irish Famine 1845–52 (Dublin, 2006).

P. O’Sullivan (ed.), The meaning of the Famine (Leicester, 1996).

For a longer version of this article and 30 contemporary documents go to: http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/Private_Responses_to_the_Famine3344361812.