‘The strange thing I am’: his father’s son?

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 2 (Mar/Apr 2006), News, Volume 14

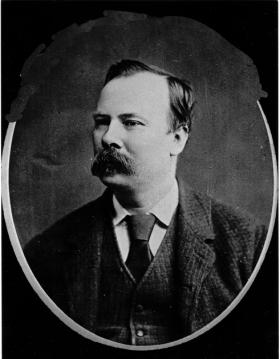

James Pearse—archetypical Victorian working-class autodidact. (Pearse Museum)

—Patrick Pearse (Autobiography)

James Pearse was born on 8 December 1839 into a poor London family. When he was between the ages of seven and eight, the family moved to Birmingham. He had limited formal education and his brief experience of the local Sunday school was not a success—the clergyman who ran it labelled him an atheist, which, according to his son’s autobiography, ‘he duly became’. He passed through a series of unsatisfactory jobs until he eventually found his niche as a sculptor’s apprentice. Patrick describes his father as

‘. . . working in the daytime and in the Art School every evening, he read books by night and came to know most of English literature well and some of it better than most men who have lived in universities.’

James Pearse thus became an archetypical Victorian working-class autodidact. His books, many of which survive in the Pearse Museum collection, reflect a man with wide interests. He read books on art and architecture, history, theology, philosophy and current affairs. He had many books on religion, but this seems to have been the result of his interest in the ‘secularist’ or ‘free thought’ movement, which disputed the central tenets of Judaeo-Christianity. He was a follower of the freethinker Charles Bradlaugh MP. Bradlaugh was a confirmed republican and a champion of universal suffrage, votes for women, birth control, land reform, workers’ rights and the rights of subject peoples in the British Empire. Although he was not a revolutionary and did not support the separation of Ireland and Britain, his republicanism led to contacts with several leading Fenians.

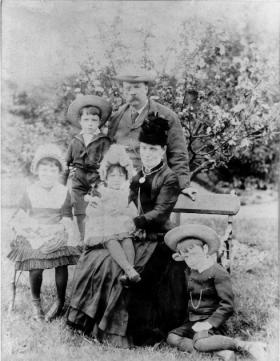

James Pearse would have had to be most discreet about his atheist views when he finally settled in Ireland in the 1860s with his English wife, Emily Suzanna Fox. Both they and their children converted to Catholicism, probably for business reasons. Emily died in 1876, leaving him a widower with two young children. He married his second wife, Margaret Brady, the following year and set up home over his premises in 27 Great Brunswick (now Pearse) Street. Patrick was born in November 1879, the second of their four children.

James Pearse’s business success excited jealousy amongst some of the Irish stone-carvers. A rival began a campaign against him on religious and racial grounds.

James and his second wife, Margaret, with their children (from left to right) Margaret, Willie, Mary Brigid and Patrick. (Pearse Museum)

James mounted a stout defence of his position and attested to the sincerity of his conversion in a letter to Archdeacon Kinnane of Fethard in 1883. However, the following year he invested £50 in a debenture with the Freethought Publishing Company headed by Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant. Even a cursory look at the publications of this organisation, which challenged and ridiculed religious faith, would suggest that James Pearse was not a believer. There is also evidence to suggest that he may have published anti-religious free-thought pamphlets under the pseudonym ‘Humanitas’.

Ironically, the only pamphlet James Pearse published under his own name is supportive of the Catholic Church. A reply to Professor Maguire’s pamphlet ‘England’s duty to Ireland’ as it appears to an Englishman was written in 1886 in response to a pamphlet by Dr Thomas Maguire, Professor of Moral Philosophy at Trinity College. Maguire’s is an extreme piece of anti-home rule polemic. In his reply (which is four times as long) James Pearse shows himself to be an ardent Parnellite. While at times he seems overly anxious to display his own learning, one cannot help admiring the bravery and confidence of this self-educated working man taking on a member of the academic élite.

James Pearse died on 5 September 1900, while staying in his brother’s home in Birmingham. He left an estate valued at £1,470–17s–6d. Pearse and Sons was wound up in 1910 and the capital was used to fund Patrick’s school, St Enda’s, which had recently moved to new premises in Rathfarnham. James Pearse’s legacy to the school was not simply financial. His books formed the nucleus of the library, while his engravings and sculptures joined the school’s art collection, and there are echoes of his father’s educational experience in Pearse’s insistence that, in his school, boys would develop independent minds and a genuine love of learning. He completely rejected the exam-focused rote learning that characterised his own educational experience, despite the fact that he himself was a successful product of that system.

It is also possible to see Patrick as being influenced by his father’s unorthodox religious beliefs. While Patrick Pearse was a deeply spiritual person, a regular communicant with a strong faith in God (at times betraying an almost messianic self-identification with Christ), he was by no means a conventional Catholic. He openly criticised the Catholic hierarchy as editor of An Claidheamh Soluis in 1903 and as editor-proprietor of An Barr Buadh in 1912. The setting up of St Enda’s as a school for Catholic boys outside the control of the church was a brave move and can hardly have been popular with the hierarchy, who jealously guarded their control of the education of their flock. In his literary works characters have religious and spiritual crises that are resolved outside of the structures of the institutional church. By the time of the Rising Pearse had, to quote Ruth Dudley Edwards, ‘abandoned the doctrines (if not the practices) of conservative Irish Catholicism and adapted his deeply felt religion to his own needs’.

However much Pearse may have loved and admired his father, he was also uncomfortable at times with his mixed heritage. He saw it as responsible for making him ‘the strange thing I am’. In 1912 he wrote an uncharacteristically revealing self-critique in his short-lived newspaper An Barr Buadh:

‘I don’t know if I like you or not, Pearse. I don’t know if anyone does like you. I know full many who hate you . . . Pearse you are too dark in yourself. You don’t make friends with Gaels.

Plaster maquette for a statue of Erin Go Breagh commissioned from Pearse and Sons for 34 College Green. (Pearse Museum)

In this piece, he associates his Englishness with the negative aspects of his personality, his melancholia and emotional distance from others. Significantly, in his autobiography Pearse describes his father as having exactly these negative traits. Was it this negativity about his English background that led to Pearse’s own zealous embrace of all things Irish?

The ‘Pearse myth’ created in the early years of the new Irish state had no place for Pearse’s freethinking English father. The conservative Irish Catholic establishment portrayed Pearse as a respectable, church-going schoolteacher and ignored most of his more radical and innovative views. The revisionists leading the radical reassessment of Pearse’s reputation during the 1970s and ’80s were often equally uninterested in a more complex understanding of Pearse’s identity. But if we look at him as the child of both his parents, as both a traditionalist and a modernist, a religious believer unafraid to question his faith, we may find Pearse to be a founder of the Irish nation who is in tune with many of the complexities of modern Ireland today.

Brian Crowley is Assistant Curator at the Pearse Museum, Dublin.

Further reading:

B. Crowley, ‘“His father’s son”: James and Patrick Pearse’, Folk Life 43 (2004–5).

Pearse and Sons, 27 Great Brunswick (now Pearse) Street. (Pearse Museum)