The Sorcery Trial of Alice kyteler by Bernadette Williams

Published in

Features,

Issue 4 (Winter 1994),

Medieval History (pre-1500),

Volume 2

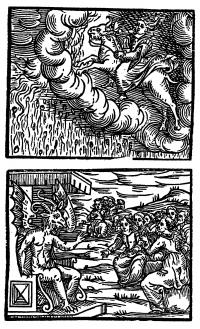

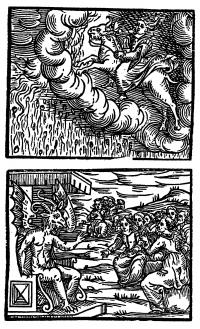

Woodcuts first published in Milan

(1626) in the Compendium

Maleficarum.

Above: Natural disasters were blamed

on witches – this shows a witch, riding

a great beast through the sky, causing

a rain of fire to descend.

Below: at the Devil’s court.

In 1324, Richard Ledrede, bishop of Ossory, declared that his diocese was a hotbed of devil worshippers. The central figure in this affair was Alice Kyteler, a wealthy Kilkenny woman who stood accused of witchcraft by her stepchildren. It was the first witchcraft trial to treat the accused as heretics and the first to accuse a woman of having acquired the power of sorcery through sexual intercourse with a demon, features which later became common in the famous witchcraft trials of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was also the occasion for a major confrontation between secular and ecclesiastical authority. In theory the state claimed control over the materiallife of its subjects and the church over the spiritual life. While this principal of separation was acknowledged by both parties the dividing line was often disputed as each jealously and zealously guarded their own rights in their separate law courts.

Alice Kyteler

The Kytelers were a family of Flemish merchants who had settled in Kilkenny, probably in the area known as Flemingstown, sometime during the mid thirteenth century. In 1280 Alice Kyteler married William Outlaw, a wealthy Kilkenny merchant and moneylender, by whom she had a son, also called William, subsequently her chief business partner; wives and mothers of medieval merchants frequently participated in the family business. He was declared an adult in 1303 and was at one point the sovereign or mayor of Kilkenny. By 1302 Alice was already married to her second husband, Adam Ie Blund of Callan, another moneylender. Alice and Adam were evidently prosperous: in 1303 William Outlaw declared he was guarding £3,000 of their money, an indication of the measure of medieval trade in Kilkenny and the highly profitable nature of money lending (a day’s wage for a labourer was one to oneand- a-half pennies). In 1307 Adam Ie Blund quit-claimed to his stepson William Outlaw, i.e. handed over all his goods, chattels, jewels, etc. and cancelled any debts owed to him by William. As Adam Ie Blund had children of his own we can begin to understand why accusations were later brought against Alice by her stepchildren. By 1309 Alice had already married her third husband, Richard de Valle, a wealthy Tipperary landowner and again her son William Outlaw benefited financially from the marriage. Some time before 1316 Richard de Valle died and Alice took legal proceedings against her stepson, also called Richard de Valle, for withholding her widow’s dower. By 1324, when she was accused of witchcraft, Alice had acquired a fourth husband, the knight Sir John Ie Poer.

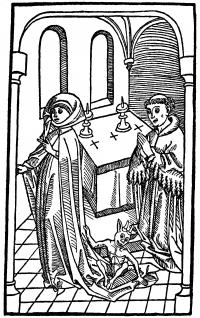

Devil and Woman. Late 15th century woodcut shows a woman leaving the altar with a demon riding the tail of her cloak.

Jealous stepchildren

The wealth that Alice had accumulated at the expense of her stepchildren had made them angry and suspicious; they came to the conclusion that she was practising witchcraft and accused her to the ecclesiastical authorities of maleficium or witchcraft, a fairly commonplace accusation and one usually treated by English law as a petty criminal offence. Witchcraft was a form of magic and magic had always existed in one form or another. Popular medicine was often based on herbal preparations made by good witches. The idea of witchcraft as an inversion of Christianity, however, came to the fore in the eleventh or twelfth century. In the latter part of the thirteenth century the Church began to view witchcraft as a heresy, as devil worship rather than the performance of a magical ritual. In 1258 Pope Alexander IV legislated in favour of inquisitional prosecution for sorcery on the grounds that it savoured of heresy.

Richard Ledrede, bishop of Ossory

Alice Kyteler’s stepchildren brought their complaint of witchcraft in 1324 to Richard Ledrede, bishop of Ossory, a particularly single-minded churchman anxious to defend the liberties and jurisdictions of the Church. Since his arrival in Ireland in 1317 as a papal appointee, Ledrede had demonstrated a zeal for reform and strict adherence to the laws of the church. He clashed with the local Anglo-Irish and complained directly to the pope. Ledrede’s patron, Pope John XXII (1316-1334), had a lively fear of sorcery and claimed that his life was in danger from witchcraft, which he listed as a heresy in his bull Super illius specula. As a papal appointee, Ledrede attempted to put into practice in Ossory the inquisitorial principles that he had learnt at Avignon, then seat of the papacy.

Spiritually negligent women and observant

demons – a common theme condemning

inattention at divine services.

Seven charges

Seven charges were brought against Alice Kyteler and her associates: that they were denying Christ and the church; that they cut up living animals and scattered the pieces at cross roads as offerings to a demon called the son of Art in return for his help; that they stole the keys of the church and held meetings there at night; that in the skull of a robber they placed the intestines and internal organs of cocks, worms, nails cut from dead bodies, hairs from the buttocks and clothes from boys who had died before being baptised; that, from this brew, they made potions to incite people to love, hate, kill and afflict Christians; that Alice herself had a certain demon as incubus by whom she permitted herself to be known carnally and that he appeared to her either as a cat, a shaggy black dog or as a black man, aethiopis, from whom she received her wealth; and that Alice had used sorcery to murder some of her husbands and to infatuate others, with the result that they gave all their possessions to her and her son, William Outlaw, thus impoverishing her stepchildren. Furthermore they claimed that Alice’s fourth husband, Sir John Ie Poer, was being poisoned. A description of him in 1324, as emaciated, with nails torn out and body hair removed-all consistent with arsenic poisoning, lends credence to the latter accusation.

Complex legal procedure

Initially relying on ecclesiastical authority, the bishop wrote to the king’s chancellor in Ireland-second only to the justiciar in rankdemanding the arrest of Alice Kyteler, citing as his authority the decretal or law Ut inquisitionis (1298) which, for the protection of the faith, directed the secular powers to obey diocesan bishops, arrest those accused and deliver them into the power or prisons of the bishops. Ledrede quoted this decretal on every possible occasion. Therein lay the seeds of conflict. The question of whether the secular power should arrest a heretic solely upon the authority of a bishop or inquisitor was precisely what became the issue in this case. The chancellor was Roger Outlaw, prior of the Order of Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem at Kilmainham and a relative of Alice’s first husband- he may even have been his brother. He urged the bishop to abandon the case or to adjourn it indefinitely. Ledrede refused point blank. The chancellor refused Ledrede’s request for the arrest of Alice on the grounds that he could not issue the warrant until a public prosecution had been held, the witches had been excommunicated, and forty days had elapsed. The bishop summoned Alice to appear before him, but she had in the meantime fled to Dublin. She probably went to Roger Outlaw because he sent advocates to Kilkenny to speak on her behalf on the appointed day. Ledrede followed the legal proceedings laid down by the chancellor to the last detail and excommunicated Alice, even though she had not been present. Ledrede cited William Outlaw and a day was appointed for Alice’s son to appear before the bishop. He was charged not only with heresy but also with harbouring and protecting heretics. William Outlaw had a powerful friend in Kilkenny, the seneschal Arnold Ie Poer. The seneschal was the representative of the lord of the liberty and therefore its chief judge and official. The seneschal, in order to block Ledrede, arrested and imprisoned him for seventeen days, until the day appointed for William to appear in the bishop’s court had passed. This was a dangerous move as an ecclesiastical decretal, Si quis suadente (1139), forbade the laying of violent hands on a monk or cleric. Moreover, it was an action viewed so seriously that only the pope himself could absolve such an assault. The sheriff, Stephen Ie Poer, and his men approached the bishop to arrest him, showed him the warrant and informed him that if he resisted they had orders to raise a hue and cry against him; the sheriff’s men had the horns hung around their necks for this very purpose. Ledrede had no intention of resisting arrest but, being very astute, he showed the seal on the warrant to the people around him and asked if they recognised it as Arnold Ie Poer’s. They did and he put the warrant in his own pocket saying he would retain it. He subsequently displayed it in Dublin as proof of Arnold Ie Poer’s. offence. Ledrede also made certain that the arrest was legal by instructing the sheriff to lay his hand on him or on his horse’s bridle or to touch him with his staff of office as was required by law. He also refused the sheriff’s suggestion that he seek the equivalent of bail as it would be an admission that Arnold Ie Poer was entitled to arrest him.

Diocese under interdict

While in prison Ledrede placed his diocese under interdict. No baptisms, marriages or burials could take place in the diocese until the interdict had been lifted. At a time when an absolute belief in the existence of hell and hellfire existed, as it most certainly did in the middle ages, such an interdict was most grave. The bishop also gave instructions for the Host to be brought to him, indicating that the body of Christ was imprisoned. The bishop proceeded to hold virtual court in the prison and the clergy and the laity flocked to visit him. While Ledrede was imprisoned, the seneschal sent a crier to every market village to see if anyone wanted to lay complaints against the bishop or his household. William Outlaw, hoping to find evidence against him, went to the archives of the chancery of the liberty of Kilkenny and found there an old accusation against the bishop which had been cancelled and quashed. William had it written out again and he then rubbed on the writing with his shoes to age it before presenting it to the seneschal who then attempted to force the bishop to answer the charges listed in it in his secular court. Ledrede refused saying he could only answer on temporal matters before the king of England and, moreover, he was not bound to answer charges before men who had been excommunicated. When eventually Arnold Ie Poer sent his uncle, the bishop of Leighlin, and the sheriff to release Ledrede, he would not leave quietly stating, ‘It will not do for a bishop imprisoned for his faith in Christ to walk out of this prison as if he were a thief or murderer’. He sent for his vestments and eventually left the prison in full regalia accompanied in procession by clergy and laity. After his release from prison, Ledrede again cited William Outlaw and his mother to appear before him but before the day appointed a sergeant arrived with a royal writ requiring the bishop to appear in Dublin before the justiciar of Ireland to explain why he had placed an interdict on his diocese and to answer complaints made by Arnold Ie Poer against him. Ledrede sent a proctor on his behalf explaining that he dare not travel to Dublin as he would have to pass through Arnold Ie Poer’s lands. His excuse was not accepted and his ecclesiastical superior, the vicar of the archbishop of Dublin, lifted the interdict.

An ignorant low-born vagabond from England’

An ignorant low-born vagabond from England’The next confrontation occurred in Kilkenny when the seneschal’s court was sitting and the bishop requested permission to address the court to plead for the arrest of the heretics. Arnold Ie Poer refused. But the fiery bishop was not going to let this pass unchallenged. He arrived at the liberty court dressed in full episcopal regalia carrying a copy of the decretal concerning heretics and accompanied by Dominicans, Franciscans and his whole cathedral chapter. Holding the Host in front of him, he forced his way into Arnold’s court. Arnold’s response was to order his ejection, call him ‘an ignorant low-born vagabond from England’ and then order him to stand in the dock. The bishop, holding up the Host, declaimed ‘Woe, woe, woe, that Christ should be sent to stand at the bar, a thing unheard of since he stood trial before Pontious Pilate’. He then held up a copy of the decretal and said that even though Arnold Ie Poer, as a knight, could read a little he nevertheless would read out the decretal so that Arnold could not at a later date plead ignorance of the matter. Arnold Ie Poer showed his contempt for Ledrede and the papal bull by saying Take your decretals to church and preach your sermons there’, and attempted to have him forcibly removed but Ledrede was carrying the host at the time so the assault was now not only upon him but upon the body of Christ. Ledrede then left on his own terms after once again ordering Arnold Ie Poer to arrest Alice Kyteler and William Outlaw.

!["St]()

At this juncture, Alice Kyteler retaliated and accused Ledrede of defamation of character claiming that without a summons, or conviction, she had been excommunicated. She appealed on these legal grounds to the Dublin court who summoned the bishop to appear before them. Again Ledrede sent a proctor to explain his case. He also complained bitterly that Alice was free to consort with her friends in Dublin and that she was usually placed with great men and leaders of the land at public assemblies; an indication of the status enjoyed by Alice Kyteler even in Dublin.

Ledrede did eventually appear in the Dublin court but only when he was certain that he would have support. The chancellor had sent a royal letter under the great seal of the king summoning the bishop to appear at the parliament in Dublin before the justiciar of Ireland and the lords temporal and spiritual. In other words his fellow bishops would be present. Not only the bishops appeared but so too did Arnold Ie Poer and William Outlaw, dressed in the livery of the seneschal. Both sides now argued their case. Arnold Ie Poer claimed that he was not bound to obey Ledrede’s commands, saying ‘if some vagabond from England has obtained his bull in the pope’s court, we do not have to obey it unless enjoined on us by the king’s seal.’ The most interesting aspect of the court were the words of Ie Poer to appeal for solidarity from his fellow Anglo-Irish against the Englishman, bishop Ledrede: As you well know, heretics have never been found in Ireland, which has always been called the ‘Island of Saints’. Now this foreigner comes from England and says we are all heretics and excommunicates … Defamation of this country affects everyone of us, so we must all unite against this man’.

Flight of Alice Kyteler

Despite Ie Poer’s plea, it was inevitable that the case would swing in Ledrede’s favour. Insults and attacks on the church and its bishops could not be lightly tolerated and he was allowed to pursue his case in Kilkenny. Alice Kyteler, sensing that public opinion was gathering against her, fled from Dublin and was never heard of again. She probably fled to England or Flanders. Her less wealthy associates were now imprisoned in Kilkenny and the bishop examined them personally using the inquisitorial procedure allowed by the papal decree. They confessed. Meanwhile the Dublin officials had arrived in Kilkenny. The chancellor stayed as a guest in William Outlaw’s house where he and the treasurer Walter de Islip, held banquets: Ledrede now formally accused William Outlaw of heresy and harbouring heretics. William confessed and submitted himself on bended knee to the bishop and was imprisoned in Kilkenny castle. His very influential friends forced Ledrede to commute the sentence to a penance and release him. William had to hear three masses every day for one year, give food to the poor and undertake to cover the roof of St Canice’s cathedral with lead. Hearing that William was not carrying out his penance, Ledrede imprisoned him once again.

On that same day, Petronilla de Midia, the maidservant of Alice Kyteler, was burnt at the stake as a heretic. She had been whipped six times on the order of the bishop. The use of torture to extract confessions was legal according to church law but not according to secular law. Ledrede never explained why she alone suffered the full punishment ‘ while the other accused were released on payment of securities.Her death was reported by the Kilkenny Franciscan chronicler, John Clyn: Petronilla de Midia … was condemned for sorcery, lot taking and offering sacrifice to demons, consigned to the flames and burned. Moreover before her even in olden days it was neither seen nor heard of that anyone suffered the death penalty for heresy in Ireland. William Outlaw now succumbed fully and requested the bishop to visit him in prison and prostrated himself in the mud before Ledrede and a large crowd of clergy and laity. His penance was increased. He was to make a visit to the Holy Land on the first available boat, the portion of the cathedral roof to be covered with lead was increased and he was given four years to complete the task. In 1332 the weight of the lead caused the roof of St Canice’s to cave in.

Conclusion

Two points in particular are worthy of comment in this episode in Irish history. Firstly, if it was not for the witchcraft trial we would scarcely be aware of Alice Kyteler-how many other financially successful women were there in medieval Ireland? Secondly, despite all the episodes of lawlessness in medieval Ireland that we hear about, the law did exist; it was understood and it was applied.

Bernadette Williams lectures in medieval history at Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading: L.S. Davidson and J.O. Ward, The Sorcery Trial of Alice Kyteler (New York 1993). R. Kieckhefer, European Witchcraft Trials: Their Foundation in Popular and Learned Culture 1300-1500 (London 1976). R. Kieckhefer, Magic in the Middle Ages (Cambridge 1990). A.C. Kors and E. Peters (eds.), Witchcraft in Europe 11 00-1700: a documentary history (philadelphia 1972).

An ignorant low-born vagabond from England’

An ignorant low-born vagabond from England’