The seditious library of Archibald Hamilton Rowan

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2016), Volume 24The seditious library of Archibald Hamilton Rowan

By Fergus Whelan

Two years after the death of the United Irishman Archibald Hamilton Rowan (1751–1834), his library at Rathcoffey House, Co. Kildare, was catalogued by Charles Sharpe of Dublin. The catalogue lists nearly 3,000 books and pamphlets. Sharpe declared that as well as ‘many very attractive volumes, the collection contained numerous scarce and valuable pamphlets, tracts, and brochures relating to France, the United States of North America, Great Britain and Ireland’. The collection embodies a comprehensive record of the controversies that engaged republicans, radicals and political reformers for two centuries, from the English Civil War until 1834, the year of Rowan’s death.

The earlier material may have been collected by Rowan’s grand-father, William Rowan (d. 1767). The old man bequeathed his name and his fortune to his grandson. He also apparently encouraged an interest in books and the importance of preserving writings relating to the political and religious controversies of his own and earlier times. The elder Rowan collected works by republicans of the Cromwellian era such as John Milton, James Harrington, Edmund Ludlow and Algernon Sydney. Following the restoration of Charles II in 1660, these writers came under pressure and there was a concerted effort to consign their work to oblivion. Milton lived in hiding for a period to avoid arrest on account of his services to Oliver Cromwell. Harrington was confined to the Tower, accused of treason. Edmund Ludlow, the regicide, escaped the axe by fleeing to the Continent. The less fortunate Algernon Sydney was executed in 1683 for his alleged involvement in the ‘Rye House plot’ to assassinate Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York.

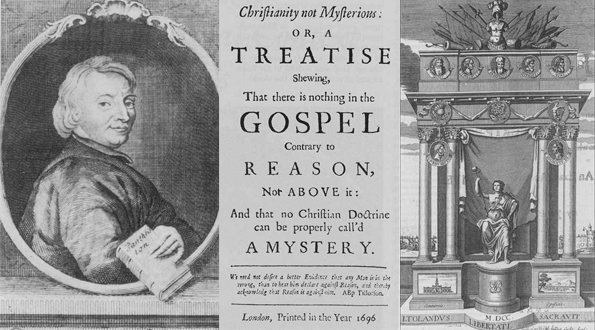

John Toland

John Toland (1670–1722), the controversial Irish philosopher, had fled Dublin in 1697 after his book Christianity not mysterious had been burnt by the public hangman. In London he set himself the task of popularising Milton, Harrington, Ludlow and Sidney by republishing their works with a brief account of their lives. He sought to inspire a new generation by rehabilitating the reputations of the ‘Commonwealth men’. Toland’s efforts met with some success. He transformed the reputation of Algernon Sidney from would-be regicide and assassin into the foremost hero-martyr of the radical Whigs of the eighteenth century and beyond. Sidney was admired by Thomas Jefferson, William Drennan, the founder of the United Irish Society, and, perhaps surprisingly, Winston Churchill.

In Dublin in the 1730s the publisher William Bruce reissued some of Toland’s work. In 1737 he published Toland’s The Oceana of James Harrington ESQ; and his other works: with an account of his life prefixed. This edition was in Rowan’s library, along with several other works by Toland. Rowan’s grand-father and almost 300 others subscribed to this edition. The subscription list includes a number of earls, viscounts and clergymen of the established church, including Ireland’s premier peer, the earl of Kildare. It may seem strange that such pillars of the establishment would publicly associate themselves with a republican tract, the first edition of which had been dedicated to Oliver Cromwell. The subscribers were also allowing their names to be associated with John Toland, who had been run out of Ireland a generation earlier, accused of heresy and atheism.

The times were auspicious, however, as the authors advanced by Toland and Bruce had all been avowed enemies of the Stuart dynasty. When Bruce’s edition of Oceana appeared, the Stuarts (then in exile in Rome) remained a threat to the Hanoverian monarchy of George II. The subscribers to Toland’s book were most likely Whigs, or at least wanted the world to believe that they were not Jacobites but rather loyal Hanoverians.

William Bruce prevailed on a number of his friends from his student days at Glasgow to subscribe to Toland’s book. His cousin Francis Hutcheson had left Dublin a few years previously to occupy the chair of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow. Hutcheson’s name is listed amongst the subscribers, as are those of Revd John Abernethy (1670–1740), Revd Samuel Haliday (1685–1739) and James Arbuckle. These were amongst a group who while at Glasgow University had come under the influence of Robert Molesworth, possibly the most radical Irish Whig politician of his era. They later formed a ‘Glasgow colony’ in Dublin, the leading personalities of whom were Molesworth and Hutcheson. Another member of the ‘colony’ was Revd Thomas Drennan, father of William Drennan. He had come to Dublin with Hutcheson to teach at a Protestant Dissenter academy. The Molesworth–Hutcheson circle is said to have handed to ‘a second generation a patriotic spirit that included all Irishmen in its loyalties and diffused a liberal philosophy throughout more than one city or country’.

John Toland (1670–1722), the controversial Irish philosopher. Both his Christianity not mysterious (frontispiece, centre) and The Oceana of James Harrington ESQ (illustration, right) were in Rowan’s library.

New Light Presbyterians

William Bruce was associated with the Wood Street New Light Presbyterian congregation in Dublin. A number of members of that congregation subscribed to his Oceana. Two members of the Damer family and four members of the Weld family appear on the subscription list. These were descendants of Joseph Damer (1630–1720), who had been a cavalry officer in the New Model Army, and Revd Edmund Weld, who had come to Dublin with Oliver Cromwell in 1649. The Damer and Weld families remained associated with Protestant Dissent in Dublin over several generations. The Wood Street congregation moved to Strand Street in 1763 and Archibald Hamilton Rowan was associated with that congregation for more than 40 years from 1785.

No theological collection of a Dissenter would have been complete without Foxe’s Book of martyrs, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s progress or Isaac Watt’s Lyric poems. Rowan, however, also had many less common and more controversial theological works on his shelves. Benjamin Hoadley (1676–1761) was an Anglican bishop who delighted Dissenters by attacking the divine authority of kings and clergy and denying the power of the church over individual conscience. Hoadley’s Answers, published in London in 1718, and his Measures of submission enquired into and disproved (1711) had pride of place on Rowan’s shelves.

The library contained many works which advanced or refuted the Unitarian case. Amongst the pro-Unitarian tracts listed is Revd John Abernethy’s Sermons of the perfection of God. The first edition of this book had been published by Bruce in Dublin in 1740, the year of Abernethy’s death. The copy in Rowan’s library was published in London in 1757. This suggests that the influence of the Molesworth–Hutcheson circle extended well beyond the city of Dublin and lasted beyond their lifetimes.

Rowan’s collection contains works by and about eminent reformers and radicals who had been his friends or with whom he had associated during his long and remarkable life. Such works included The letters of John Wilkes (1725–97), The poems of Charles Churchill (1732–64) and The proceedings of the sheriffs of Dublin against Charles Lucas. Wilkes, Churchill and Lucas were friends of Gawin Hamilton, Rowan’s father, and during his early manhood Rowan had enjoyed their company in his London home in the late 1760s.

Revd John Abernethy—his Sermons of the perfection of God (1740) is amongst the pro-Unitarian tracts listed.

Joseph Priestley

The library contains several works by Rowan’s friend Dr Joseph Priestley, the scientist and educationalist. Priestley wrote prolifically on an eclectic range of subjects, from science to English grammar and politics, and included his Appeal to the public on the riots in Birmingham. Priestley had fled to America in 1794 after his house had been burnt to the ground by a ‘Church and King mob’ who objected to his support for the French Revolution. Rowan had joined Priestley in Pennsylvania in 1796.

Also featured in the collection are the memoirs of John Horne Tooke (1736–1812) and Major John Cartwright (1740–1824), two celebrated British political reformers. Tooke was a supporter of John Wilkes and was a defendant in the famous ‘treason trials’ in London in 1794. His name was mentioned several times during the trial of William Jackson, the French agent at the centre of the plot that led to Rowan’s flight from Ireland in 1794.

Vindication of the rights of women

Cartwright was an advocate of universal suffrage and had been a supporter of Thomas Paine’s Rights of man. Rowan’s edition of Rights of man in two volumes was published in Dublin in 1792. He also had Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the rights of women, published in Dublin in 1793, and a number of works by her husband, William Godwin. Rowan had been close to Wollstonecraft during their exile in Paris in 1795, and he was the constant companion of Godwin when living in London from 1803 to 1806. Mary Shelley, the daughter of Wollstonecraft and Godwin, wrote Frankenstein in 1818, and Rowan’s copy was published in London in 1831. He also had a number of works by Mary Shelley’s husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, who is said to have met with Rowan in 1813 when visiting Dublin.

The library held an extensive collection of records of trials and prosecutions of several of Rowan’s friends. Some of them were acquitted, some transported to the penal colonies, and three were executed. Horn Tooke and John Thelwall were acquitted; Thomas Muir and Thomas Palmer, the Scottish Martyrs, were transported to Botany Bay, which amounted to a death sentence in slow motion. Neither of them ever saw Scotland again. Thomas Russell, Robert Emmet and Colonel Edward Marcus Despard were hanged and beheaded.

William Hamilton Rowan in 1822.

No reference to Tone or Lord Edward Fitzgerald

Rowan owned two other libraries, at Killyleagh Castle and Leinster Street in Dublin. This probably explains why the Rathcoffey catalogue contains no reference to his two dearest comrades, Theobald Wolfe Tone and Lord Edward Fitzgerald, both of whom died in gaol in agony in 1798. Wolfe Tone’s diary had been published in 1831, the year before Rowan’s death, so we do not know whether he had read it or owned a copy. We can be certain that Rowan had read Thomas Moore’s Life of Edward Fitzgerald because in 1830 he publicly challenged the author over suggestions that Samuel Neilson had betrayed Fitzgerald in ’98. Moore wrote to Rowan, graciously accepting the latter’s forceful assertion that Neilson was no traitor.

Fergus Whelan’s God-provoking democrat: the remarkable life of Archibald Hamilton Rowan was published last year by New Island Press.